Conformation - factors for racing ability - what might increase the chances to pick a future star on the racecourse

By Judy Wardrope

Everyone wants to be able to pick a future star on the track, ideally, one that can compete at the stakes level for several seasons. In order to increase the probability of finding such a gem, many buyers and agents look at the pedigree of a horse and the abilities displayed by its relatives, but that is not always an accurate predictor of future success. When looking at a potential racehorse, the mechanical aspects of its conformation usually override the lineage, unless of course, the conformation actually matches the pedigree.

For our purposes, we will examine three horses at the end of their three-year-old campaigns and one at the end of her fourth year. In order to provide the best educational value, these four horses were chosen because they offer a reasonable measure of success or failure on the track, have attractive pedigrees and were all offered for sale as racing prospects in a November mixed sale. The fillies were also offered as broodmare prospects.

Is it possible to tell which ones were the better racehorses and predict the best distances for those who were successful? Do their race records match their pedigrees? Let’s see.

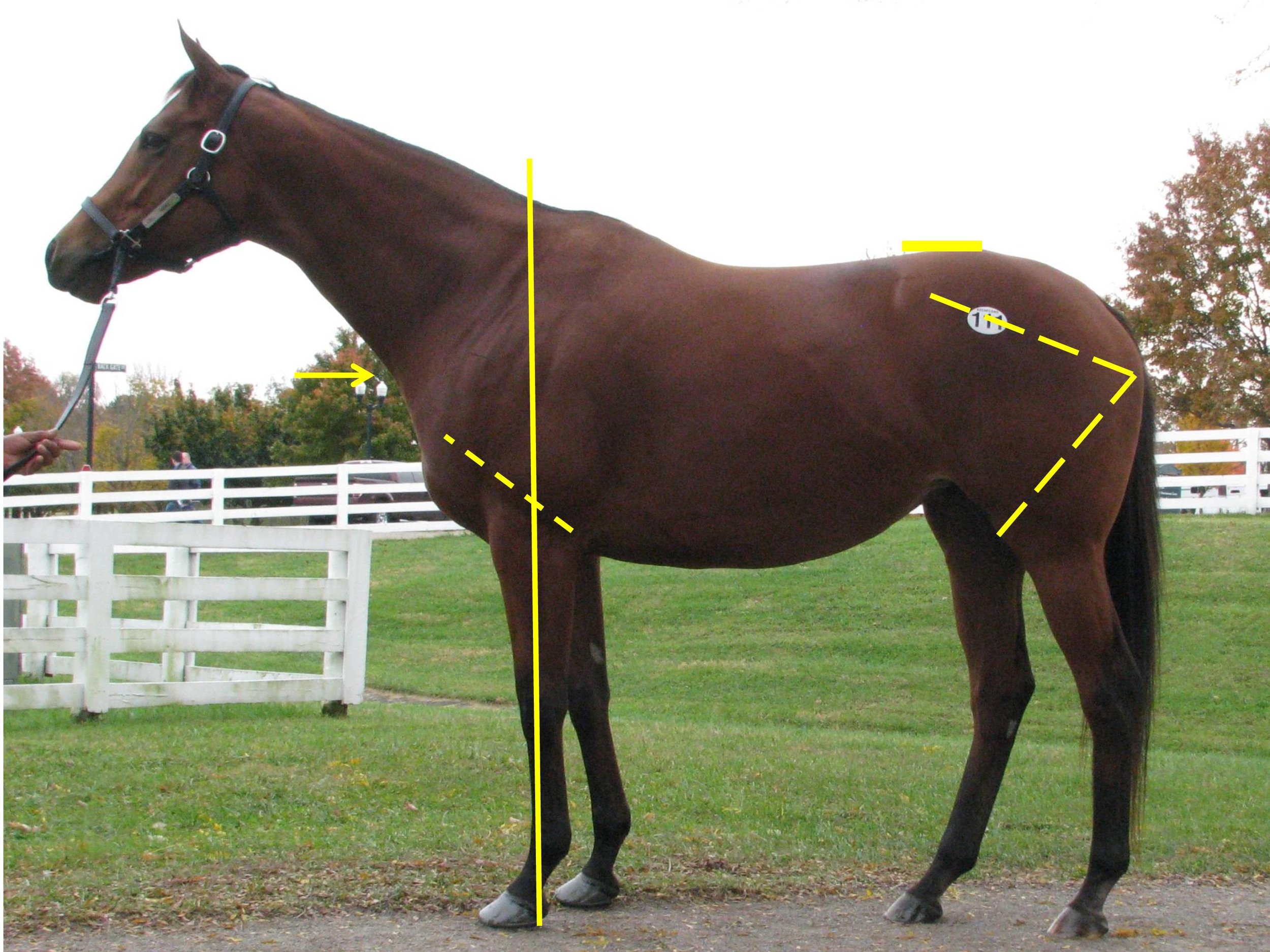

Horse #1

Horse #1

This gelding (photographed as a three-year-old) is by Horse of the Year Mineshaft and out of a daughter of Giants Causeway, a pedigree that would suggest ability at classic distances. He brought a final bid of $275k as a yearling and $45k as a maiden racing-prospect at the end of his three-year-old year after earning $19,150. His story did not end there, however. He went back to racing, changed trainers a few times, was claimed and then won a minor stakes at a mile while adding over $77k to his total earnings. All but one of his 18 races (3-3-3) were on the dirt, and he was still in training at the time of writing.

Structurally, he has some good points, but he is not built to be a superior athlete nor a consistent racehorse. His LS gap (just in front of the high point of croup) is considerably rearward from a line drawn from the top point of one hip to the top of the other. In other words, he was not particularly strong in the transmission and would likely show inconsistency because his back would likely spasm from his best efforts.

His stifle placement, based on the visible protrusion, is just below sheath level, which is in keeping with a horse preferring distances around eight or nine furlongs. However, his femur side (from point of buttock to stifle protrusion) of the rear triangle is shorter than the ilium side (point of hip to point of buttock), which not only adds stress to the hind legs, but it changes the ellipse of the rear stride and shortens the distance preference indicated by stifle placement. Horses with a shorter femur travel with their hocks behind them do not reach as far under their torsos as horses that are even on the ilium and femur sides. While the difference is not pronounced on this horse, it is discernable and would have an effect.

He exhibits three factors for lightness of the forehand: a distinct rise to the humerus (from elbow to point of shoulder), a high base of neck and a pillar of support (as indicated by a line extended through the naturally occurring groove in the forearm) that emerges well in front of the withers. The bottom of his pillar also emerges just into the rear quarter of his hoof, which, along with his lightness of the forehand, would aid with soundness for his forequarters.

The muscling at the top of his forearm extends over the elbow, which is a good indication that he is tight in the elbow on that side. He developed that muscle in that particular fashion because he has been using it as a brake to prevent the elbow from contacting the ribcage. (Note that the tightness of the elbow can vary from side to side on any horse.)

He ran according to his build, not his pedigree, and may well continue to run in that manner. He is more likely to have hind leg and back issues than foreleg issues.

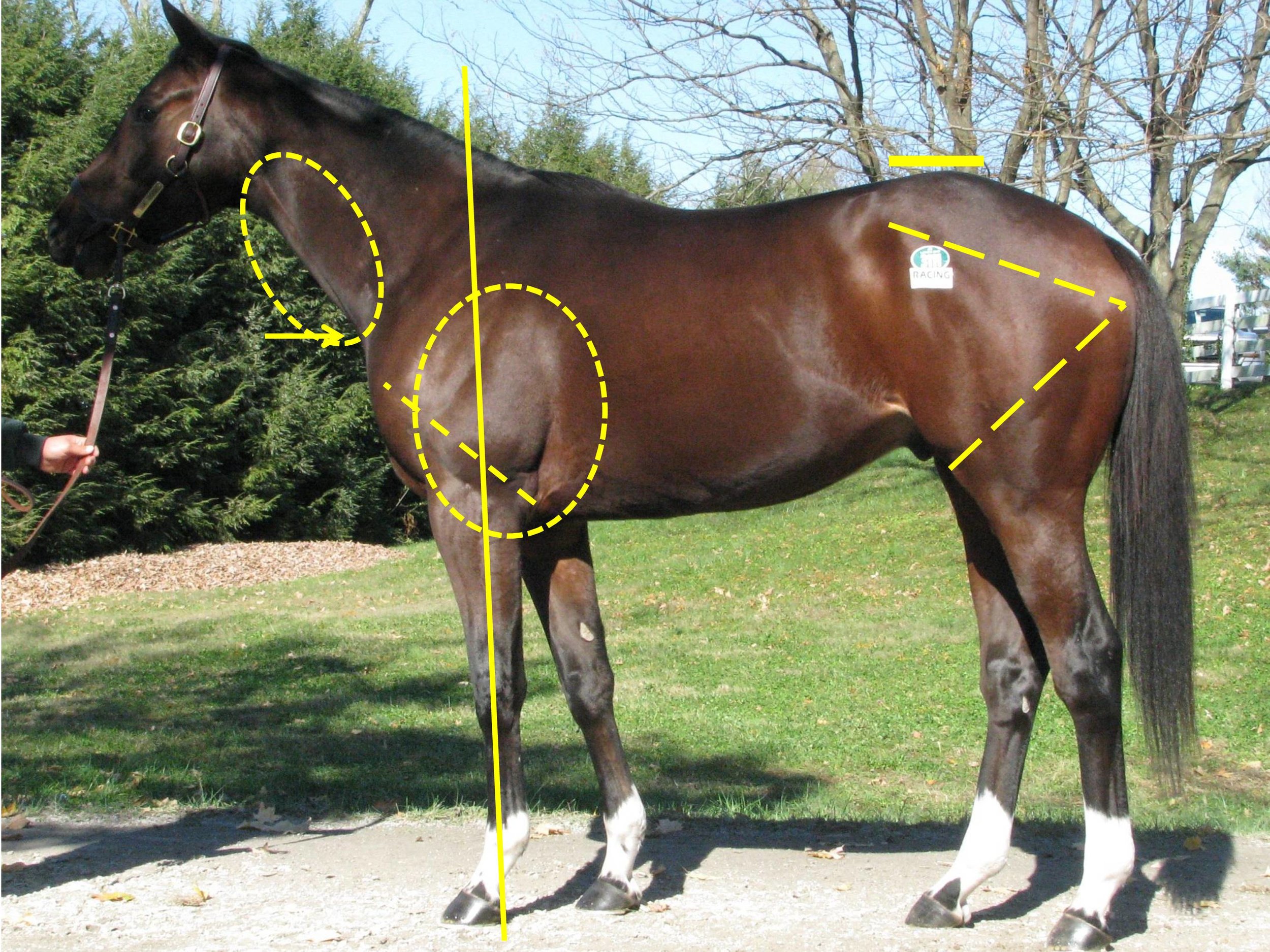

Horse #2

Horse #2

This filly (photographed as a three-year-old) is by champion sprinter Speightstown and out of a graded-stakes-placed daughter of Hard Spun that was best at about a mile. The filly raced at two and three years of age, earning $26,075 with a lifetime record of 6 starts, one win, one second and one third—all at sprinting distances on the dirt. She did not meet her reserve price at the sale when she was three.

Unlike Horse #1, her LS gap is much nearer the line from hip to hip and well within athletic limits. But, like Horse #1, she is shorter on the femur side of her rear triangle, which means that although her stifle protrusion is well below sheath level, the resultant rear stride would be restricted, and she would be at risk for injury to the hind legs, particularly from hock down.

She only has two of three factors for lightness of the forehand: the top of the pillar emerges well in front of the withers, and she has a high point of neck. Unlike the rest of the horses, she does not have much rise from elbow to point of shoulder, which equates with more horse in front of the pillar as well as a slower, lower stride on the forehand. In addition, the muscling at the top of her forearm is placed directly over her elbow… even more so than on Horse #1. She would not want to use her full range of motion of the foreleg and would apply the brake/muscle she developed in order to lift the foreleg off the ground before the body had fully rotated over it to avoid the elbow/rib collision. This often results in a choppy stride. However, it should be noted that the bottom of her pillar emerges into the rear quarter of her hoof, which is a factor for soundness of the forelegs.

Her lower point of shoulder combined with her tight elbow would not make for an efficient stride of the forehand, and her shorter femur would not make for an efficient stride of the hindquarters.

Her construction explains why she performed better as a two-year-old than she did as a three-year-old. It is likely that the more she trained and ran, the more uncomfortable she became, and that she would favor either the hindquarters or the forequarters, or alternate between them.

She did not race nearly as well as her lineage would suggest.

Horse #3

Horse #3

This filly (photographed as a three-year-old) is by champion two-year-old, Midshipman, and out of a multiple stakes-producing daughter of Unbridled’s Song. She raced at two and three years of age and became a stakes-winner (Gr3) as a three-year-old, tallying over $425k in lifetime earnings from 12 starts. Although she did win one of her two starts on turf, she was best at 8 to 8.5 furlongs on the main track. She brought a bid of $775k at the sale and was headed to life as a broodmare.

Her LS gap is just slightly rearward of a line drawn from hip to hip and is therefore well within the athletic range. Her rear triangle is of equal distance on the ilium and femur sides, plus her stifle protrusion would be just below sheath level if she were male. She has the engine of an 8- to 9-furlong horse and the transmission to utilize that engine.

Aside from all three factors for lightness of the forehand (pillar emerging well in front of the withers, good rise of the humerus from elbow to point of shoulder and a high base of neck), the bottom of her pillar emerges into the rear quarter of her hoof to aid in soundness.

Although she shows muscle development at the top of her forearm, the muscling does not extend over her elbow the way it does on the previous two horses. Her near side does not exhibit the tell-tale muscle of a horse with a tight elbow, and thus, she would be comfortable using a full range of motion of the forehand.

Proportionately, she has the shortest neck of the sample horses, which may be one of the reasons she has developed the muscle at the top of her forearm. Since horses use their necks to aid in lifting the forehand and extending the stride, she may compensate by using the muscle over her humerus to assist in those purposes.

Of the sample horses, she is the closest to matching heritage and ability. …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

Conformation and Breeding Choices

By Judy Wardrope

A lot of factors go into the making of a good racehorse, but everything starts with the right genetic combinations; and when it comes to genetics, little is black and white. The best we can do is to increase our odds of producing or selecting a potential racehorse. Examining the functional aspects of the mare and then selecting a stallion that suits her is another tool in the breeding arsenal.

For this article we will use photos of four broodmares and analyze the mares’ conformational points with regard to performance as well as matings likely to result in good racehorses from each one. We will look at qualities we might want to cement and qualities we might hope to improve for their offspring. In addition, we will look at their produce records to see what has or has not worked in the past.

In order to provide a balance between consistency and randomness, only mares that were grey (the least common color at the sale) with three or more offspring that were likely to have had a chance to race (at least three years old) were selected. In other words, the mares were not hand-picked to prove any particular point.

All race and produce information was taken from the sales catalogue at the time the photos were taken (November 2018) and have not been updated.

Mare 1

Her lumbosacral gap (LS) (just in front of the high point of croup, and the equivalent of the horse’s transmission) is not ideal, but within athletic limits; however, it is an area one would hope to improve through stallion selection. One would want a stallion with proven athleticism and a history of siring good runners.

The rear triangle and stifle placement (just below sheath level if she were male) are those of a miler. A stallion with proven performance at between seven furlongs and a mile and an eighth would be preferable as it would be breeding like to like from a mechanical perspective rather than breeding a basketball star to a gymnast.

Her pillar of support emerges well in front of the withers for some lightness of the forehand but just behind the heel. One would look for a stallion with the bottom of the pillar emerging into the rear quarter of the hoof for improved soundness and longevity on the track. Her base of neck is well above her point of shoulder, adding additional lightness to the forehand, and she has ample room behind her elbow to maximise the range of motion of the forequarters. Although her humerus (elbow to point of shoulder) shows the length one would expect in order to match her rear stride, one would likely select a stallion with more rise from elbow to point of shoulder in order to add more lightness to the forehand.

Her sire was a champion sprinter as well as a successful sire, and her female family was that of stakes producers. She was a stakes-placed winner at six furlongs—a full-sister to a stakes winner at a mile as well as a half-sister to another stakes-winning miler. Her race career lasted from three to five.

She had four foals that met the criteria for selection; all by distance sires of the commercial variety. Two of her foals were unplaced and two were modest winners at the track. I strongly suspect that this mare’s produce record would have proven significantly better had she been bred to stallions that were sound milers or even sprinters.

Mare 2

Her LS placement, while not terrible, could use improvement; so one would seek a stallion that was stronger in this area and tended to pass on that trait.

The hindquarters are those of a sprinter, with the stifle protrusion being parallel to where the bottom of the sheath would be. It is the highest of all the mares used in this comparison, and therefore would suggest a sprinter stallion for mating.

Her forehand shows traits for lightness and soundness: pillar emerging well in front of the withers and into the rear quarter of the hoof, a high point of shoulder plus a high base of neck. She also exhibits freedom of the elbow. These traits one would want to duplicate when making a choice of stallions.

However, her length of humerus would dictate a longer stride of the forehand than that of the hindquarters. This means that the mare would compensate by dwelling in the air on the short (rear) side, which is why she hollows her back and has developed considerable muscle on the underside of her neck. One would hope to find a stallion that was well matched fore and aft in hopes he would even out the stride of the foal.

Her sire was a graded-stakes-placed winner and sire of stakes winners, but not a leading sire. Her dam produced eight winners and three stakes winners of restricted races, including this mare and her full sister.

She raced from three to five and had produced three foals that met the criteria for this article. One (by a classic-distance racehorse and leading sire) was a winner in Japan, one (by a stallion of distance lineage) was unplaced, and one (by a sprinter sire with only two starts) was a non-graded stakes-winner. In essence, her best foal was the one that was the product of a type-to-type mating for distance, despite the mare having been bred to commercial sires in the other two instances.

Mare 3 ….

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

An Introduction to the Functional Aspects of Conformation

By Judy Wardrope

Why is one horse a sprinter and another a stayer? Why is one sibling a star and another a disappointment? Why does one horse stay sound and another does not? Over the course of the next few issues, we will delve into the mechanics of the racehorse to discern the answer to these questions and others. We will be learning by example, and we will be using objective terminology as well as repeatable measures. This knowledge can be applied to the selection of racing prospects, to the consideration of distance or surface preferences and, of course, to mating choices.

Introducing a different way of looking at things requires some forethought. Questions need to be addressed in order to provide educational value for the audience. How does one organise the information, and how does one back up the information? In the case of equine functionality in racing, which horses will provide the best corroborative visuals?

After considerable thought, these three horses were selected: Tiznow (Horse #1) twice won the Breeders’ Cup Classic (1¼ miles) ; Lady Eli (Horse #2) won the Juvenile Fillies Turf and was twice second in the Filly and Mare Turf (13/8 miles); while our third example (Horse #3) did not earn enough to pay his way on the track. Let’s see if we can explain the commonalities and the differences so that we can apply that knowledge in the future.

Factors for Athleticism

If we consider the horse’s hindquarters to be the motor, then we should consider the connection between hindquarters and body to be the horse’s transmission. Like in a vehicle, if the motor is strong, but the transmission is weak, the horse will either have to protect the transmission or damage it.

According to Dr. Hilary M. Clayton (BVMS, PhD, MRCVS), the hind limb rotates around the hip joint in the walk and trot and around the lumbosacral joint in the canter and gallop. “The lumbosacral joint is the only part of the vertebral column between the base of the neck and the tail that allows a significant amount of flexion [rounding] and extension [hollowing] of the back. At all the other vertebral joints, the amount of motion is much smaller. Moving the point of rotation from the hip joint to the lumbosacral joint increases the effective length of the hind limbs and, therefore, increases stride length.” From a functional perspective, that explains why a canter or gallop is loftier in the forehand than the walk or the trot.

In order to establish an objective measure, I use the lumbosacral (LS) gap, which is located just in front of the high point of the croup. This is where the articulation of the spine changes just in front of the sacrum, and it is where the majority of the up and down motion along the spine occurs. The closer a line drawn from the top point of one hip to the top point of the other hip comes to bisecting this palpable gap, the stronger the horse’s transmission. In other words, the stronger the horse’s coupling.

We can see that the first two horses have an LS gap (just in front of the high point of the croup as indicated) that is essentially in line with a line drawn from the top of one hip to the top of the opposing hip. This gives them the ability to transfer their power both upward (lifting of the forehand) and forward (allowing for full extension of the forehand and the hindquarters). Horse #3 shows an LS gap considerably rearward of the top of his hip, making him less able to transfer his power and setting him up for a sore back.

You may also notice that all three of these sample horses display an ilium side (point of hip to point of buttock), which is the same length as the femur side (point of buttock to stifle protrusion)—meaning that they produce similar types of power from the rear spring as it coils and releases when in stride. We can examine the variances in these measures in more detail in future articles, when we start to delve into various ranges of motion as well as other factors for soundness or injury.

Factors for Distance Preferences…

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Shunted heels - Avoiding cracks with proactive management

Functionally adapted for speed and efficient use of energy, the thoroughbred foot is thin-walled and light compared to other breeds. This adaptation for speed renders the hoof more susceptible to hoof capsule distortions, or shape changes that interfere with the normal function of the foot, which are: support, traction, shock dissipation, and proprioception.

Is Conformation Relevant?

This year’s yearling sales are just beginning with Fasig-Tipton July in Kentucky quickly followed by Fasig-Tipton August taking place in Saratoga. Then it is the turn of the monstrous Keeneland September catalogue to lay host to thousands of blue-blooded Thoroughbreds desperate to have their conformation analyzed by trainers, owners and those conformation experts – the bloodstock agents. The 2007 September Keeneland yearling sale sold nearly four thousand horses for just short of four hundred million dollars in seven books, each illustrated with photographs of the current superstars sold at last year’s sale. Does examining a horse’s conformation really give you a better idea as to whether you are looking at next year’s superstar?

James Tate BVMS MRCVS(10 July 2008 - Issue Number: 9)

By James Tate

This year’s yearling sales are just beginning with Fasig-Tipton July in Kentucky quickly followed by Fasig-Tipton August taking place in Saratoga. Then it is the turn of the monstrous Keeneland September catalogue to lay host to thousands of blue-blooded Thoroughbreds desperate to have their conformation analyzed by trainers, owners and those conformation experts – the bloodstock agents. The 2007 September Keeneland yearling sale sold nearly four thousand horses for just short of four hundred million dollars in seven books, each illustrated with photographs of the current superstars sold at last year’s sale. Does examining a horse’s conformation really give you a better idea as to whether you are looking at next year’s superstar?

If you visit the saddling enclosure before the Breeders’ Cup, you will notice that some of the runners are offset at the knee, toe in or toe out, have long pasterns or perhaps even sickle hocks and curbs. Then you could visit the saddling enclosure before a maiden claimer and you would see just how many of these poor performers have good conformation. The racing media only concentrates on the good horses whose conformation often becomes exaggerated by winning lots of races. The legendary John Henry, the richest gelding in history, was unmistakably small, ugly, temperamental and back at the knee, but there are millions of other horses just as poorly conformed to which our attention is never drawn. In the same way, there are many poor performers with technically perfect conformation but we are led to believe that Secretariat’s conformation is superior because he won the Triple Crown.

Many U.S. trainers believe that training methods, tight turns and the unforgiving dirt surface make it difficult for horses to overcome poor conformation. Indeed, an argument could perhaps be made that some of the high-profile poorly conformed European Champions such as the dual guineas winning filly Attraction, may not have done so well on the other side of the pond. However, John Henry is far from the last Grade One winning performer with less than perfect conformation. Real Quiet, who missed out on the Triple Crown by a nose in the Belmont, passed through the sale ring as a yearling with both imperfect conformation and a poor veterinary report. Baffert said “When I bought Real Quiet for $17,000, I didn’t vet him. I just bought the athlete. I’ve had horses that didn’t pass the vet when they were yearlings and then went on to become great racehorses.” Five-time Grade One winner Congaree had poor knee conformation but that did not stop this giant colt winning twelve times in twenty-five career starts. Steve Asmussen will be hoping that his massive superstar Curlin continues his current great win streak, which includes the Breeders’ Cup Classic, the Dubai World Cup and now the Stephen Foster Handicap despite his less than perfect limbs. Ken McPeek purchased him at the yearling sales despite imperfect forelimb conformation as well as an OCD in his front ankle.

One thing is certain – a perfectly conformed horse in all areas except one bent foreleg will cost considerably less than the same horse with perfect conformation. Is it really correct to pay so much more to have little or no conformational faults, or should we be concentrating on certain faults and not others, or perhaps pedigree, size and stamp are more important? One only has to stand in the Keeneland sales pavilion for a minute to hear the phrase “I couldn’t buy a horse with hocks like that.” At this point, I would like to question the evidence supporting an opinion like this. Mike Ryan, one of the most successful yearling buyers in the history of auction sales believes that “it’s not a beauty contest where we should be looking for the perfect specimen. It is easy to find what you don’t like about a horse and strike him off the list. I go the other way and start with what I like about a horse. Then I look at whatever faults are there and ask myself, ‘Does he look like a runner?’ ‘Does he have the demeanor of a good horse?’ Good horses usually overcome their faults.” This article will attempt to illustrate some aspects of conformation before examining some of the available evidence concerning its scientific relevance to performance.

Conformation is defined as the form or outline of an animal but it may be expanded to include its movement. The conformation of the Thoroughbred racehorse today is a result of a combination of natural selection and the demands we have put on it. The assessment of a horse’s conformation is a personal process but many begin with the body, move onto the limbs and then assess the horse’s movement. The conformation of the body assesses the horse’s balance and center of gravity but in my opinion is an underestimated area of the assessment. Conformation textbooks detail limb ‘faults’ for pages after pages, but hardly mention assessing the future athlete’s body as a whole. When examining a yearling as a potential superstar surely it is vital to assess the whole horse– its height, length, width, girth and muscle mass, not to mention its neck, head, outlook and temperament.

When examining the biomechanics of the galloping Thoroughbred, one can see that its propulsion comes from its backend, hence the commonly held belief that sprinters are bigger in this area than distance horses. It also makes sense that any horse should have a large body allowing plenty of room for the heart and lungs. Good distance horses do not always have large girths but they are usually long, whereas sprinters are often shorter but stronger with a large girth and a big muscular back end. As a result, professional horsemen tend to use comments such as short-coupled, weak behind, weak necked, narrow and tubular. I would also suggest that this is an area in which so-called amateur owners can provide valuable insight when looking at yearlings, as some ‘experts’ seem to spend too much time assessing minor details and forget to look at the horse!

The assessment of limb conformation is quite complex but it is not a matter of opinion – a curb is a curb and back at the knee is back at the knee – conformation can change a little as the horse matures, but usually it is the onlooker’s assessment that varies, not the horse. The horse is assessed from a number of angles both at rest and in motion. Both hindlimb and forelimb conformation is important but their functions should not be forgotten – the hindlimb is providing most of the athlete’s propulsion whereas perhaps the most important function of the forelimb is simply not to break under the considerable pressure of training and racing.

Much is said about the side-on conformation of the knee in relation to the rest of the forelimb and everyone seems to have a different opinion. The 2007 Consignors and Commercial Breeders Association ‘Vet Work Plain and Simple’ booklet interviewed a cross-section of leading trainers with regard to conformational faults. Christophe Clement believes that “training methods in the U.S. make it difficult to overcome being back at the knee” and Carla Gaines, Eoin Harty, Bob Hess, Larry Jones, Richard Mandella, and Kiaran McLaughlin all supported his view to some extent. Yet in the same publication, Todd Pletcher is not so concerned by this conformational fault, stating that a lot of his best horses have been back at the knee and John Kimmel goes so far as to say that he would not buy a horse who was significantly over at the knee. From a veterinary perspective, horses who are over at the knee have extra strain placed on their sesamoid bones and the suspensory ligament, whereas horses who are back at the knee have extra strain placed on their knee ligaments, as well as having extra force placed on the front of their knee bones, thus knee chip fractures should theoretically be more common in such horses. However, statistical evidence for such injuries is severely lacking and as an anecdote, the over at the knee colt in the photograph has fairly major knee problems, whereas the back at the knee filly is a winner who has barely taken a lame step throughout two years of training!

Many buyers will also not buy a horse with long sloping pasterns, but is this sensible? A long sloping pastern theoretically predisposes a horse to injury of the flexor tendons, sesamoid bones and the suspensory ligaments. However, upright pasterns, which are not considered to be anything like such a serious fault, theoretically predispose a horse to fetlock joint injuries, ringbone of the pastern joint and navicular disease. The pastern angle is also irreversibly linked with the horse’s foot. This is a part of the horse that is often underestimated by non-professionals but trainers cannot help but notice poor feet as they seem to spend their entire lives trying to keep them right. Club feet are hated by trainers but also severely disliked are boxy feet, flat feet, contracted heels and unbalanced feet just waiting to form quarter cracks when training commences.

When looking at a yearling’s forelimb from the front there are several terms that are widely used – base-wide/base narrow, toed-out/toed-in and offset/rotated from the knee and/or fetlock, not to mention whether the horse is considered to have enough forelimb strength or ‘bone’. In order to be accurate, the yearling must be standing squarely and in most circumstances the horse’s gait will mirror its forelimb conformation. While none of the conformations listed above are considered desirable, all are seen in the paddock for most Grade One races, which is hardly surprising when it is remembered that although the forelimb has great relevance to the future superstar’s soundness, it has very little relevance to its future ability.

The hindlimb of the racehorse is where the majority of its propulsion comes from and therefore, despite the fact that there is slightly less lameness here than in the forelimb, their conformation is every bit, if not more, important. Whilst some of the forelimb conformational points carry relevance to the hindlimb, for example, pastern angle and foot-path, some new points have to be considered. When assessing the horse from side-on, the hindlimb/hock position is generally considered to be either ‘sickle-hocked,’ ideal or ‘camped behind.’ Sickle-hocked horses are predisposed to curbs (injury of the plantar ligament) and considered to have weak hind legs. However, it is also considered a ‘fault’ to have the limb too far behind the body as it is likely to be associated with upright pasterns. Also, there are horsemen who believe that a horse should not have an excessively straight hindlimb as this theoretically predisposes the horse to hock arthritis and a ‘locked stifle.’

When assessing the horse from behind, the onlooker is assessing pelvic and muscle symmetry as well as hindlimb conformation. ‘Cow-hocked’ horses are criticized because there is excessive strain on the inside of the hock joint, which may cause hock arthritis. This comment should be taken lightly when assessing yearlings as to some extent this is a normal conformation in weak, growing, young Thoroughbreds. ‘Bow-legged’ yearlings are also criticized as it is believed that excessive strain is placed on the outside aspect of the limb. These bow-legged horses which are base-narrow behind are often prone to knocking themselves at exercise.

Having considered some of the conformational faults of the Thoroughbred and cited some of the reasons why these may cause veterinary injuries, it would now make sense to advise potential purchasers to avoid horses with any significant conformational faults. However, the statistical evidence must be considered first. In 2002, one of the most renowned equine orthopedic surgeons in the world, Dr Wayne McIlwraith, presented the findings of his research into Thoroughbred conformation leading him to famously question corrective surgery performed on foals. His research concluded that “a perfectly correct leg is not ideal for soundness” and some degree of carpal valgus can be a good thing. The extensive study came up with several mildly unexpected conclusions. A longer toe increases the odds of knee problems, a longer shoulder decreases the odds of a fracture and offset knees lead to fetlock problems, not knee problems. The study also found that a longer pastern predisposes to forelimb fractures, Thoroughbred foals achieve 95% of their full height by 18 months of age and manipulating the knee for cosmetic reasons is not helpful and can actually contribute to unsoundness.

McIlwriath is not the only person to have carried out valuable research into this area. The late English veterinarian and trainer Peter Calver conducted a much more extensive survey of the conformation of Thoroughbred yearlings seen at the British sales. The study categorized and looked for statistical differences in the performances of many different conformations, for example: Back at the knee, offset and weak hocks. It concluded that the pedigree was more important than any conformational fault and that it was difficult to determine if conformation actually affected performance at all, or if horses performed poorly due to other, inherited characteristics, such as heart and lung function or size.

In summary, assessing the conformation of a Thoroughbred yearling is complex, personal and of questionable relevance. The size and shape of a future athlete should be relevant, as should its limb conformation. However, neither is proven to be relevant in determining whether or not it can win a Grade One race. This is the beauty of the sales – what one man loves, another hates, and no-one knows for sure who is right until at least a year or two down the line!