Equine Nutrition - be wary of false feeding economies

Article by Louise Jones

Many horses, especially performance horses, breeding stallions, and broodmares at certain stages of production, require additional calories in the form of hard feed. Whilst in the current economic climate, with rising costs and inflation, it might be tempting to look at lower cost feeding options; in reality, this could be a false economy. When choosing a feed, in order to ensure that you are getting the best value for money and are providing your horses with the essential nutrients they require, there are a number of factors to consider.

Quality

The ingredients included in feed are referred to as the raw materials. These are usually listed on the feed bag or label in descending order by weight. Usually they are listed by name (e.g., oats, barley wheat) but in some cases are listed by category (e.g., cereals). Each raw material will be included for a specific nutritional purpose. For example, full-fat soya is a high-quality source of protein, whilst cereals such as oats are mainly included for their energy content, also contributing towards protein, fibre and to a lesser degree, fat intake.

Waste by-products from human food processing are sometimes used in the manufacture of horse feed. Whilst it is true that they do still hold a nutritional value, in most cases they are predominantly providing fibre but contain poor levels of other essential nutrients. Two of the most commonly used by-products are oatfeed and distillers grains. Oatfeed is the fibrous husks and outer layer of the oat and it mainly provides fibre. Distillers grains are what is left over after yeast fermentation of cereal grains used to produce alcohol. The leftover grain is dried and used in the feed industry as a protein source. Distillers grains can be high in mycotoxins, which are toxic chemicals produced by fungi in certain crops, including maize. Furthermore, despite being used as a protein source, distillers grains are typically low in lysine. As one of the first limiting amino acids, lysine is a very important part of the horse’s diet; horses in work, pregnant mares and youngstock all have increased lysine requirements.

Another ingredient to look out for on the back of your bag of feed is nutritionally improved straw, often referred to as “NIS”. This is straw that has been treated with chemicals such as sodium hydroxide (caustic soda) to break down the structural fibre (lignins) and increase its digestibility. Straw is a good example of a forage which contains filler fibre; in fact, you can think of it as the horse’s equivalent of humans eating celery. Traditionally, oat straw was used to make NIS, however many manufacturers now use cheaper wheat or barley straw due to the rising cost of good quality oat straw. Not all companies state what straw is used and instead use generic terms such as cereal straw, which again, allows them to vary the ingredients used depending on cost and availability.

By law, feed manufacturers must declare certain nutrients on the feed bag, one of which is the percentage crude protein. This tells you how much protein the feed contains. However, not all protein is created equal; some protein is of very high quality, whilst other proteins can be so low in quality that they will limit a horse’s ability to grow, reproduce, perform or build muscle. Protein ‘quality’ is often measured by the levels of essential amino acids (e.g., lysine, methionine) it contains. In most cases feed manufacturers do not have to list the amount of these essential amino acids; but looking at the ingredient list will give you a clue as to how good the protein quality is. Good sources of high-quality protein include legumes and soybean meal, whereas by-products often contain moderate- or low-quality protein, even though they may be relatively high in crude protein.

Understanding more about the ingredients in your bag of horse feed will help you to assess whether they are providing good, quality nutrition. Feeds containing large proportions of lower quality ingredients will obviously be cheaper, but this could compromise quality of the products. The goal therefore is to ensure that the nutritional makeup of the products remains high quality and consistent.

Cooking for digestibility

Digestibility is a term used to describe the amount of nutrients that are actually absorbed by a horse and are therefore available for growth, reproduction, and performance. Understanding digestibility of energy sources—such as fibre, fat, starch, and sugar as well as protein, vitamin and mineral digestibility—is important when devising optimal diets for horses.

Most of the energy in grains is contained in the starch; however, horses cannot fully digest starch from uncooked (raw) grains in the small intestine, which results in this undigested starch traveling into the hindgut where it will ferment and potentially cause hindgut acidosis. Therefore, in order to maximise pre-caecal digestibility, feed manufacturers cook the grain. Similarly, soya beans must be carefully processed prior to feeding them to horses. This is because raw soybeans contain a specific enzyme that blocks the action of trypsin, an enzyme needed for protein absorption.

There are various methods of cooking including pelleting, micronizing, extrusion, and steam-flaking. This is a fine art as, for example, undercooking soya beans will not deactivate the enzymes correctly, thus resulting in reduced protein absorption. On the other hand, overcooking will destroy essential amino acids such as lysine, methionine, threonine, and possibly others.

Variation in cooking methods, and hence digestibility, can have a direct impact on how the finished product performs. Your individual feed manufacturer should be able to tell you more about the cooking processes they use to maximise digestibility.

Micronutrient and functional ingredients specification

The back of your bag of feed should list the inclusion of vitamins, such as vitamin E, and minerals including copper and zinc. A lower vitamin and mineral specification is one way feed companies can keep the cost of their products down. For example, the vitamin E level in one unbranded Stud Cube is just 200 iu/kg—50% lower than in a branded alternative.

For most vitamins and minerals, the levels declared on the back of the bag/label only tell the amount actually added and do not include any background levels provided by the raw materials. In other marketing materials, such as brochures, some companies will combine the added figure with the amount provided by other raw materials in order to elevate the overall figure. For example, a feed with 50 mg/kg of added copper may list the total copper as 60 mg/kg on their website or brochure. Whilst it is perfectly acceptable to do this, it is equally important to recognise that background levels in different raw materials can vary and hence should not be relied upon to meet requirements. To complicate this slightly further, chelated minerals (e.g., cupric chelate of amino acids hydrate, a copper chelate) may be included. Chelated minerals have a higher bioavailability, and so a feed with a high inclusion of chelated copper may perform as well as one that has an even higher overall copper level but does not include any chelates.

Equally important is the need to verify that any specific functional ingredients such as prebiotics or yeast are included at levels that are likely to be efficacious.

Feeding rates

Whilst the cost of a bag of feed is undeniably important, another aspect that should be considered is the amount of feed required to achieve the desired body condition and provide a balanced diet. Feeding higher volumes of hard feed not only presents a challenge from a gastrointestinal health point of view but also increases the cost per day of feeding an individual. For example, the daily cost of feeding 8kg of a feed costing £400/€460 per tonne vs 5¼ kg of a feed costing £600/€680 per tonne are exactly the same. Plus, the lower feeding rate of the more expensive product will be a better option in terms of the horse’s digestive health, which is linked to overall health and performance. To keep feeding costs in perspective, look at the cost of feeding a horse per day rather than relying on individual product prices.

Consistency

When a nutritionist creates a recipe for a horse feed, they can either create a ‘set recipe’ for the feed or a ‘least cost formulation’. A set recipe is one that doesn’t change and will use exactly the same ingredients in the same quantities. The benefit of this is that you can rest assured that each bag will deliver the same nutritional profile as the next. However, the downside is that if the price of a specific ingredient increases, unfortunately, so will the cost of the product.

On the other hand, least-cost formulations use software to make short-term recipes based on the cost of available ingredients. It will use the cheapest ingredient available. When done correctly, they will provide the amount of calories (energy), crude protein, vitamins and minerals as specified on the label. However, the ingredients will change, and protein quality can be compromised. Often feed companies using least-cost formulations will print their ingredients on a label, rather than the bag itself, as the label can be amended quickly and cheaply, should they alter the recipe.

Checking the list of ingredients in your feed regularly should alert you to any formulation changes. Equally look out for feeds that include vague ingredient listings such as ‘cereal grains and grain by-products, vegetable protein meals and vegetable oil’; these terms are often used to give the flexibility to change the ingredients depending on how costly they are.

Peace of mind

Another important issue is that some companies producing lower-cost feeds may not have invested in the resources required to carry out testing for naturally occurring prohibited substances (NOPS) such as theophylline, banned substances (e.g., zilpaterol - an anabolic steroid) or mycotoxins (e.g., zearalenone). It is true that, even with the most stringent testing regime, identifying potential contamination is difficult; and over recent years, a number of feed companies have had issues. However, by choosing a feed manufacturer who is at the top of their game in terms of testing and monitoring for the presence of such substances will give you peace of mind that they are aware of the threat these substances pose, and they are taking significant precautions to prevent their presence in their products. It is important to source horse feed from a BETA NOPS registered feed manufacturer at a minimum. It may also be prudent to ask questions about the feed manufacturer’s testing regime and frequency of testing.

Supplements – to use or not to use?

A good nutritionist will be able to assess any supplements that are fed, making note of why each is added to the diet and the key nutrients they provide. It is easy to get stuck into the trap of feeding multiple supplements that contain the same nutrients, effectively doubling up on intake. Whilst in many cases this isn’t nutritionally an issue, it is an ineffective financial spend. For example, B vitamins can be a very useful addition to the diet, but if provided in levels much higher than the horse needs, they will simply be excreted in the urine. Reviewing the supplements you are feeding with your nutritionist to ensure they are essential and eliminating nutritional double-ups is one of the simplest ways to shave off some expense.

Review and revise

A periodic review of your horse’s diet ensures that you’re providing the best nutrition in the most cost-effective way. This will require the expertise of a nutritionist. Seeking advice on online forums and social media is not recommended as this can lead to misinformed, biased advice or frankly, dangerous recommendations. On the other hand, a properly qualified and experienced nutritionist will be able to undertake a thorough diet evaluation, carefully collecting information about forages, concentrates, and supplements.

Working with a nutritionist has many advantages; they will be able to work with you to ensure optimal nutrition, whilst also helping to limit needless expenses. Some nutritionists are better than others, so choose wisely. (Does the person in question have the level of qualifications?) Bear in mind that while qualifications can assure you that the nutritionist has rigorous science-based training, experience is also exceptionally important. Ask them about their industry experience and what other clients they work with to ensure they have the right skill set for your needs. In addition, a competent nutritionist will be willing and able to interact with your vet where and when required to ensure that the health, well-being, and nutrition of your horses is as good as it can be.

There are independent nutritionists available, but you will likely incur a charge—often quite a significant one. On the other hand, the majority of feed companies employ qualified, experienced nutritionists and offer their advice, free of charge.

Always read the label – experts guide us through equine healthcare products

By Lissa Oliver

We all want what’s best for our horse and we are happy to pay a price for the benefit of a happy, healthy and peak-performing horse. But what if that price is a hefty fine, suspension or even serious health consequences for us and our staff? How much trust can we afford to place in the claims of manufacturers, and do we pay enough attention to instructions?

Ultimately, the responsibility for what goes into our horses lies fully with us. In this article, we’ll focus on the nutritional product labelling as well regulation of products which are promoted to consumers.

Nutrition

Dr Corinne Hills is an equine veterinarian with more than 20 years’ experience in practice in Canada, the Middle East, Europe, New Zealand and Australia, leading her to develop Pro-Dosa BOOST, manufactured from her own purpose-built, GMP-registered laboratory in New Zealand.

Ingredient listings

“We all want to make good choices and support our horses in the best way we can, with the best use of our finances,” Dr Hills agrees. “Horsemen always ask me about ingredients, but nobody ever asks about quality management. Similar products might appear to contain the same ingredients, but if the quality of the ingredients is poor, they will provide no benefit. Think about what you are spending your money on, and learn to read labels critically.

“It’s important to know the nutrient content of your feed and forage. In a perfect world everyone would consult their nutritionist and have forage tested, knowing exactly what their horse requires, what it is receiving and what supplements, if any, are needed. Horsemen don’t always feed a ready-prepared balanced feed. If they are mixing their own, they should be analysing the components of their feed. It’s easy and inexpensive, and your vet will know where you can send samples for analysis. Good feed companies provide the service for free.

“Simply reading the label of feed and supplements could save you quite a bit of money. In my experience most people way over-supplement. A balanced feed manufactured by a reputable company should provide all of a horse’s requirements. Adding supplements could disturb the balance of the nutrients being fed. It is worth taking the time to understand nutrition to effectively support equine health. You can go to your feed company and ask their in-house nutritionist to suggest a tailored balanced diet that will suit most horses in your stable. If the feed company doesn’t have a nutritionist, it might be worth looking around for a new feed supply.

“Metabolism is quite complex, requiring a broad range of essential nutrients to function optimally. A lot of one nutrient doesn’t make up for deficiencies in another. The balance between nutrients is important. Some nutrients are required for the uptake and function of other nutrients. Too much or too little of one nutrient may result in deficiencies or toxicities of other nutrients. Imbalances can adversely affect health, performance and recovery. At a minimum, imbalances in a feed or supplement can render a product ineffective.

“For instance, vitamin C is required for the absorption of iron from the gut. Without vitamin C, iron passes straight through the gut and out in the faeces. Vitamin E, on the other hand, has a negative interaction with iron. It binds with iron and reduces its absorption, causing much of it to be wasted. So, in order for horses to use dietary iron effectively, it must be administered with vitamin C and without vitamin E. Iron balance is also closely related to zinc, manganese, cobalt, and copper.”

Nutrients Ratio

Ca:P 1-2:1

Zn:Mn 0.7-1.1

Zn:Cu 3-4:1

Fe:Cu 4:1

“B vitamins are known to work better when administered in optimal balance with each other. Amino acids are another good example of how nutrient balance is important. The balance of amino acids in a feed is as important as the amount of protein. Imbalances in amino acids limit the amount of protein in a feed that is usable in the horse to produce proteins and muscle cells, and the wasted amino acids that can’t be used for protein synthesis create a load on kidneys, elevate body temperature and elevate heart rates.

“It is also important to adhere to the instructions on the label. If insufficient doses are given, then no impact or a negative impact on the overall health of horses may result.

“If you are buying a supplement that doesn’t contain what the label says, then at best, it’s a waste of money. At worst, it could be detrimental to your horses’ health. Giving too much of some nutrients is dangerous.”

Reading the label isn’t always an easy fix, however, as Dr Hills points out.

“Standing in a feed store, I couldn’t easily choose a good one as I couldn’t work out what was in each one by just looking at the labels. I had to photograph the labels and then put the information into a spreadsheet, convert all the quantities and units to a single standard, and then compare those contents to equine nutrient requirements.

“How many horsemen do that? And if they don’t know what they are feeding their horses, aren’t they worried?”

Dr Hills has one simple tip. “If labels are easy to understand so that you can tell at a glance what you are giving your horse, then the manufacturer is probably proud of their formulation and believe it will stand up to scrutiny.

“If you have to perform too many calculations to figure out what you are giving, there is a fair chance that the formulation isn’t great. Some companies don’t actually want you to know how much or little of each nutrient is in their product. Take the time to do the maths and make sure you are making a true comparison before picking the cheapest or prettiest product on the shelf.

“When reading labels, it is important to consider all aspects of the nutrient composition—including balance, form and dose—in relation to the nutrient requirements of your horse.

“I found a huge number of products listing different combinations of nutrients that were included in different forms. For example, calcium could be provided as calcium carbonate, tricalcium phosphate, or calcium gluconate. They were also quantified with different units of measure, such as mg/kg, %, ppm, to name only a few. Then, they were to be given in different doses.

“The most confusing paste I found listed contents in terms of parts per million (ppm), percentages, and mg/kg. Then, the syringe was in pounds and the recommended dose in ounces.”

Quality control

“How do you know if a product is manufactured safely and meets label claims?” Dr Hills asks. “This information frequently isn’t on the label, but it’s just as important as the ingredients list; so it’s well worthwhile to make the effort to source the information.

“You could look for a statement on the website about quality management, or you might have to ask the manufacturer some questions. Does the manufacturer have a quality management programme? GMP or ISO certification provides hard evidence of this.

“Be sure to ask every rep that visits your stable about quality management as they will almost certainly be the most readily available source for this information. Any rep that can’t talk competently about their company’s quality management programme probably represents a company that doesn’t have one.

“GMP stands for Good Manufacturing Practice, and this is a specific standard required for pharmaceutical producers. It is, however, voluntary for feed supplement manufacturers. A generic version of good manufacturing practice, abbreviated with small “gmp,” is a reference to a quality management system that is not government specified and inspected. It could be the same as GMP or it could be applied to a non-standardised or less complete quality system.

“If a company has either ISO or GMP certification, you can be sure that the supplements they produce will be safe, secure and generally meet label claims.

“Once you have selected a good quality, safe and healthy feed, then you can probably feed it to most of the horses at your stable. Spelling horses and smaller horses will need to eat less of it with more hay or grass. Racehorses or broodmares will need to eat more of it.”

Veterinary Medicines Directorate

The Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD) is the regulator of veterinary medicines in the UK. Louise Vodden and James Freer, from the Enforcement Department of the VMD, guide us through the draft documentation outlining the legislation behind the manufacture, sale and labelling of equine health and welfare products.

Guidance for advertising non-medicinal veterinary products

When advertising a non-medicinal veterinary product, it must not, by presentation or claims, suggest that it is medicinal.

This applies to any advert—be it in magazines, online, at trade events or through client meetings and listing materials—that is aimed in part or in full at a UK audience. It is the responsibility of anyone engaged in marketing activities to comply with the VMD.

A veterinary medicinal product is legally defined as:

Any substance or combination of substances presented as having properties for treating or preventing disease in animals.

Any substance or combination of substances that may be used in, or administered to, animals with a view either to restoring, correcting or modifying physiological functions by exerting a pharmacological, immunological or metabolic action, or to making a medical diagnosis.

Medicinal by presentation

The first part of the definition above covers products that indicate they have a beneficial effect on an animal’s state of health. This is known as “medicinal by presentation”.

Prevention

This includes the destruction of parasitic infestations on an animal that may cause a medical condition, such as flea allergic dermatitis; hence, products that kill fleas on an animal are also classified as medicines.

Disease

This is considered to cover a broad range of conditions ranging from those caused by bacterial, viral or parasitic infections, to disorders resulting from various systemic dysfunctions, or deficiencies of substances essential for survival. We generally use the catch-all term “adverse health condition” for something wrong with an animal’s state of health. This includes injuries that pose a significant risk to wellbeing or would require more than the most superficial of management.

Medicinal by function

The second part of the definition covers two further aspects. The first relates to products containing substances with a recognised medicinal effect, commonly referred to as “medicinal by function”. The second covers the purpose of putting something in, or on, an animal to effect a change (restoring, correcting, modifying) in the way a bodily system works.

Restoring

This covers claims of restoration of function in any system within an animal that, for any reason, is not functioning within the normal range for an animal of good health. Even if there is no claim, be careful not to present before and after treatment expectations in your advert. For example, in one picture the dog can barely walk, and in another the same dog scampering along apparently healed. Such an advert would be considered medicinal by presentation.

Correcting

This covers any product used to address any deficiency or dysfunction in an animal’s systems. This includes issues like nutritional deficiencies in an animal, hormone imbalances, immunomodulation to address allergic reactions and correction of digestive dysfunction.

Modification

This includes any effect that changes the way an animal functions that is not covered by restoration or correction effects. In most cases, these tend to be enhancement claims such as “boosting”, “better”, “stronger”. Where such claims are made, the immediate question is, “better than what?” If the answer is, “better than normal,” then the product is considered medicinal by presentation. If the answer is, “better than an animal with condition X,” then it is considered as claiming to be medicinal by function.

Making medicinal claims

Non-medicinal products cannot claim to treat, prevent or control any adverse health condition. Nor can it refer, expressed or implied, to the treatment or prevention of a disease or adverse condition, or to improving the state of health of the animal treated.

For example, medicinal claims include a reference to the treatment or prevention of scours, colic, footrot, laminitis, sweet itch or pathological nervous conditions—or any other condition which is not the normal state of a healthy animal. This includes references to symptoms or any indication that the product is for use in an animal which is not in a normal healthy state.

References to the nutritional maintenance of a healthy animal, healthy digestive system or healthy respiratory system would not normally be regarded as medicinal claims. Though this does not extend to claims for preventing the occurrence of an adverse health condition or its symptoms.

Any implication that the product for use in an unhealthy animal and is intended for purpose of, or has the consequential outcome of, preventing a detrimental health state in an animal would predispose the product for a medicinal purpose for which it would require a marketing authorisation. Exceptions to this include particular nutritional purpose feeds, however, there are also specific restrictions on the claims these products can make.

Things to avoid in the advertising of non-medicinal products

These products can only be presented for the maintenance of health in healthy animals.

The basic premise is that the purchaser of the product has a healthy animal and will be using it to support their animal’s state of health. Health maintenance does not include attempting to halt or slow the progression of a detrimental health state.

Association with an adverse health condition

Narratives may not be used to suggest some terrible disease will or may happen, nor using statements like “4 out of 5 get” to present the product as the solution. This is considered a medicinal claim. Occasionally this approach is prefaced with the overtly medicinal company statement of intent that “we believe prevention is better than cure”.

Reference to specific diseases may be made in the form of a safety warning where use of the product may pose a risk, for example “WARNING: Not to be fed to horses with PPID”.

Comparisons and presentation of equivalency to authorised medicines

A product not authorised as a veterinary medicine must never be presented, in any capacity, in comparison to any form of authorised medication. Marketing material for a non-medicinal product must not indicate or imply that the product can, or is intended to, be used as a substitute for authorised veterinary medicines. Nor should the use of a non-medicinal product be presented as resulting in the reduction of the use of any authorised medication. To do so is considered a medicinal claim for the product.

Disclaimers do not provide a remedy to the misrepresentation of a product in a medicinal capacity.

Testimonials, quotes and endorsements

If customer testimonials are used in connection with the marketing of a product and report results containing medicinal claims, the claims will be regarded as those of the company marketing the product.

Claims made by a third party, such as magazine reviews or articles published by independent analysts, will be regarded as those of the company marketing the product where evidence confirms that the third party has a connection to the marketing company via solicitation, endorsement, sponsorship or funding.

If, for example, a vet who has been using a product for years expresses an opinion that is not being given in support of marketing a product, then it would just be an opinion. Any material published in support of marketing the product is considered to be marketing material. Whether that material is based on professional opinion, peer review studies, customer feedback, folkloric tradition or an “everybody knows”claim is not relevant. It must still adhere to the rules governing marketing material.

Herbal or “natural” products

Herbal products, “nutraceuticals”, or any products sourced in a way generally described as “natural” are treated like any other products. A natural origin provides no exemption from these requirements; they require authorisation if they are medicinal by function or presentation.

Biocides, insecticides and repellents

The following are always medicinal products requiring a marketing authorisation due to their use on animals:

Veterinary product that contains substances that kill insects or external parasites (e.g., pyrethrins, pyrethroids or organophosphate compounds) as they are medicinal by function

Veterinary product claiming to have, or which has, the function and control of internal parasites

Veterinary product claiming to treat or prevent a disease caused by a viral, bacterial or fungal infection

The following do not require an authorisation, provided they do not claim to treat or prevent disease:

Product containing a repellent, such as diethyltoluamide or ethylhexanediol, provided it claims only to repel external insects

Product applied only to housing or bedding

Topical disinfectant applied to intact skin provided it does not claim to treat or prevent disease, including infection prevention (e.g., shampoos)

The marketing of these products is covered by legislation on biocides.

For further information regarding non-medicinal products, email enforcement@vmd.gov.uk or call +44 (0) 1932 338308 or +44 (0) 1932 338410

Feeding for Weaning Success

By Dr. Emma Hardy, PhD

The first 12 months in the life of a foal are pivotal in building the foundations for overall long-term health and optimal development. It is also during this initial year that the foal will face its first major life event in being weaned from his dam, and he must cope with the nutritional challenges this may bring.

There are many approaches to weaning and every breeder strives to make the right choices for the best outcome. The reproductive status of the mare, the cost and time available, the plans for the foal, and the physical practicalities of the yard will often dictate which type of weaning strategy should be employed. They all come with their own benefits and drawbacks. Choosing the correct feeding and nutrition programme is key to your success.

Early growth

The dam’s milk is nutritionally complete, providing all the energy and nutrients required for a foal. However, at around three months of age, milk yield peaks, then naturally starts to decline, along with suckling frequency. At the same time the foal increases its intake of non-milk feedstuff such as grass, forage, and some concentrates as the his nutritional needs begin to overtake the mare’s own supply. This period coincides with rapid weight gain, with foals reaching around 30% of their adult weight by this point.

Genetics, breed, seasonal temperature differences, and nutrient availability will all contribute to the growth rate of the foal. Small fluctuations in growth rates are normal and nothing to worry about. However, continuing or significant deviations from the National Research Council (NRC) 2007 growth recommendations can predispose the foal to health issues, most notably orthopaedic problems. The structures and tissues of the foal’s body do not grow at the same rate: bone matures earliest, followed by muscle and then fat. Indeed at 12 months of age the yearling will have attained 90% of his mature adult height, which emphasises the importance of correct diet in supporting this rapid early bone growth.

Introducing creep feed

Although the foal supplements his milk intake with small quantities of the dam’s feed and forage, the introduction of a creep feed prior to weaning can help sustain normal growth rates. Highly digestible creep feed is formulated from milk proteins and micronised grain, and it’s fortified with vitamins and minerals. In addition to encouraging growth, it promotes gastrointestinal adaptation to the post-weaning diet and is also described as a significant factor in the reduction of weaning-associated stress.

The appropriate age to introduce a creep feed depends on many factors. For the foal at pasture and doing well, there should be little need for any additional nutrition until two-to-three months of age, when milk supply begins to diminish. Earlier intervention may be necessary should the foal be orphaned or fail to thrive due to inadequate milk supply or other environmental influences.

TO READ MORE --

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

Why not subscribe?

Don't miss out and subscribe to receive the next four issues!

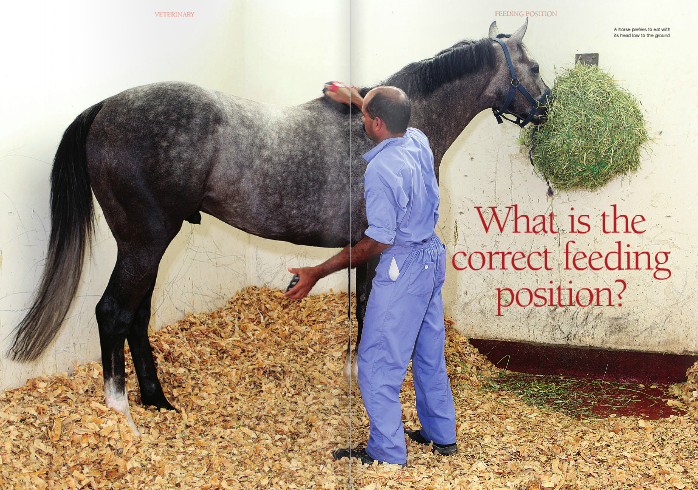

Hay Bar

Planning and building a new yard can be quite an undertaking. The horses welfare is paramount yet the design and construction must be efficient and cost effective. Running costs for any yard can become a serious financial liability and, with forage prices set to rise, it is essential that we try to find ways of becoming more economical and less wasteful.

Hay Bar is a proven sound investment in many ways. Stabled horses benefit from feeding from the floor, as it helps to maintain their natural way of foraging. This, in turn, helps to ensure that mentally they are more relaxed and that there are less respiratory, dental and physio problems, all of which can prove to be costly and, to say the least, inconvenient.

Other unnecessary and unwanted expenses are waste forage and bedding: Hay Bar helps to ensure that forage does not become contaminated and ensures the horse gets the full benefit of what he is being fed.

Labour costs are rising all the time, so it is important that time is well spent. Filling hay nets is time consuming. The Hay Bar system is labour saving, safer, more hygienic, better for our horses and the solution to numerous problems.

Tel: + 44 (0)1723 882434 for more information or visit www.haybar.co.uk

Harmony in the Stable

According to research “up to 93% of horses in training have ulcers which develop within a week of the horse going into training – brought on by a number of factors including the nutritional management of the horse in training”. A 28-day course of treatment for ulcers can cost over €1,000 but ulcers can be managed more naturally. Horses are designed to trickle-feed, grazing for up to 18 hours per day when at grass. When they are put into training, their routine changes to one of intermittent feeding and reduced forage.

There is an abundance of research to show that hay is a key component in the successful management of ulcers and recent research has shown that a small amount of hay given before exercise is also beneficial to the horse as a means of helping to reduce ulcers as it helps to buffer the acid in the stomach.

The Equus Live 2013 Innovation award winner Harmony Equine Feeder, the brainchild of veterinary physiotherapist Michelle O’Connor, is a truly revolutionary way of feeding hay that minimises waste, and mimics natural grazing patterns providing constant access to hay.

With testimonials from leading trainers and also the Army equitation school, the feeder was in trials in a number of yards in the lead up to the launch at Equus Live. The result today is a feeder that allows the horse to eat naturally at ground level, that controls how much the horse can eat (by a variable size rubber mesh) thereby mimicking the natural grazing pattern of ‘little and often’, that only needs to be filled once daily and that can be removed easily from the stable for cleaning and filling. Dust/fines fall through a hole in the bottom plate thus preventing inhalation of dust into the nostrils.

for more information call:

m: +353 (0)87 686 2399

Published European Trainer Issue 44 Winter 2013

Succulents and treats

CLICK ON IMAGE TO READ ARTICLE

THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN - EUROPEAN TRAINER - ISSUE 44

Economics of Feeding Horses in Training

While economic efficiency within any business is important to maintain profitability, there has been a particular focus on cost saving recently within the racing industry as a result of the underlying economic climate.

Feeding is an area where economies can be made, but for the best effect any cost savings should not compromise the quality of the ration to the detriment of health or performance. Equally however, we should not shy away from a critical evaluation of our feeding management on a regular basis, especially if there is an element of sticking to the same way of feeding just because 'it's always been done like that'.

Catherine Dunnett (European Trainer - issue 28 - Winter 2009)

Hemp for horses

Hemp has been synonymous with horse bedding for many years, as its fibrous properties give these products good cushioning and absorptive properties. Latterly, hemp has become popular as a food ingredient for people, being associated with well-known brands such as ‘The Food Doctor’ and ‘Ryvita’. It has also been investigated as a feed ingredient for farm animals including laying hens and dairy cows.

Hemp is primarily an oilseed crop like soya, linseed and rapeseed and it is the grain or seed that contains the majority of nutritional value. In comparison to other oilseed crops, hemp produces a very high yield and therefore it is not surprising that in recent years it has become a good economic crop for farmers in some parts of the world.

Catherine Dunnett (European Trainer - issue 27 - Autumn 2009)

Forage - So much more than just a filler

Too often thought of as just a filler or occupational therapy to while away the time between hard feeds, forage is worth so much more than that. Simply feeding an inadequate quantity of forage, or choosing forage that has an inappropriate nutrient profile, or is of poor quality can have a negative impact both on health and performance in racehorses.

Dr Catherine Dunnett (01 July 2007 - Issue Number: 4)

By Dr Catherine Dunnett

Too often thought of as just a ‘filler’, or occupational therapy to while away the time between hard feeds, forage is worth so much more than that. Simply feeding an inadequate quantity of forage, or choosing forage that has an inappropriate nutrient profile, or is of poor quality can have a negative impact both on health and performance in racehorses.

Inappropriate choice of forage and its feeding can easily lead trainers down the slippery slope towards loose droppings and loss of condition. Forage can also have a significant impact on the incidence and severity of both gastric ulcers and respiratory disease, including inflammatory airway disease (IAD) and recurrent airway obstruction (RAO).

When choosing forage the main elements to consider are

• Good palatability to ensure adequate intake

• Adequate digestibility to reduce gut fill

• Fitness to feed to maintain respiratory health

• A profile of nutrients to complement concentrate feeds

FORAGE CAN ONLY BE GOOD WHEN PALATABLE

Palatability is a key issue, as even the best forage from a quality and nutritional standpoint is rendered useless if the horses do not eat sufficient quantities on a daily basis. Palatability is a somewhat neglected area of equine research and so we largely have to draw on practical experience to tell us what our horses like and what they don’t. Some horses appear to prefer softer types of hay, whilst others prefer more coarse stemmy material. Many horses readily consume Haylage, whilst some trainers report that other horses prefer traditional hay. Apart from the physical characteristics, the sugar content of hay or haylage may affect its palatability. Forage made from high sugar yielding Ryegrass is likely to have a higher residual sugar content compared with that made from more fibrous and mature Timothy grass.

Some interesting research carried out a few years ago by Thorne et al (2005), provided some practical insight into how forage intake could be increased in the reluctant equine consumer. This work reported that the amount of time spent foraging (which will increase saliva production), was increased when multiple forms of forage were offered to horses at the same time. From a practical viewpoint this can be easily applied in a training yard and it should help to increase the amount of forage consumed. For example, good clean hay could be offered together with some haylage, and a suitable container of alfalfa based chaff or dried grass all at the same time.

A Healthy Intake

Racehorses in training often eat below what would be considered to be the bare minimum amount of forage to maintain gastrointestinal health. Whilst sometimes this is due to the amount of forage offered being restricted, in other instances it is because the horses are limiting their own intake. This may be due to either their being over faced with concentrate feed, or due to unpalatable forage being fed. Establishing a good daily intake of forage during the early stages of training and then maintaining the level through the season is important. Typically the absolute minimum amount of forage fed should be about 1% or 1.2-1.5% of bodyweight for hay or haylage, respectively. This equates to 11lb of hay or a rounded 15.5lbs of haylage for an average sized horse (1100lbs). The weight of haylage fed needs to be greater than that of hay due to the higher water content of the latter.

Intake of haylage needed to achieve a similar dry matter intake to 11lbs of hay

Moisture Dry Matter Weight of forage Percentage Increase above hay

Hay (Average) 15% 85% 11lbs

Haylage 1 30% 70% 13lbs 20%

Haylage 2 45% 55% 16.5lbs 50%

The dry matter of haylage needs to be consistent to allow a regular intake of fibre and reduce the likelihood of digestive disturbance or loose droppings. Ideally trainers should be aware of any significant change in dry matter, so that they can adjust the intake accordingly.

Forage intake is restricted in racehorses to firstly ensure that a horse consumes adequate concentrate feed to meet their energy needs and requirement for vitamins and minerals within the limit of their appetite. Secondly, the amount of forage fed is restricted in order to minimise ‘gut fill’ or weight of fibre and associated water in the hindgut, as this will restrict their speed on the racetrack.

BUT… inadequate amounts of forage in a horses’ diet has such a negative effect on health that the minimum amount fed must be kept above recognised ‘safe limits’. Choosing an early cut forage that is less mature and with more digestible fibre means that the ‘gut fill’ effect is lessened. In addition, horses can always be fed more forage during training with the daily quantity being reduced (within the safe limits) in the few days before racing where this is practical.

FITNESS TO FEED

Quality of forage, in terms of its mould, yeast and mycotoxin load, can have a major impact on respiratory health. A recent Australian report (Malikides and Hodgson 2003) highlighted the cost of inflammatory airway disease (IAD) in horses in training, in terms of loss of training time and of potential earnings, together with the associated cost of veterinary treatment. They estimated from their study group that in Australian racing up to 33% of horses in training can have lower airway inflammation, yet show no overt clinical signs.

Type and therefore quality of forage, as well as the quality of ventilation were singled out as the most significant risk factors in the development of IAD.

Forage is potentially a concentrated source of bacteria, mould spores and even harvest mites. Hay that has heated during storage, or that has been bailed with a high moisture content is likely to provide a greater load of these undesirable agents that can harbour substances that promote airway inflammation, such as endotoxin.

Purchasing good quality and clean forage from a respiratory perspective will certainly reduce the pressure placed on young racehorses’ respiratory systems. However, how does one achieve this?

• Microbiological Analysis – the price paid for a microbiological analysis of a prospective batch of hay is a worthwhile cost when the consequences of poor hay are considered.

Assuming the analysis is favourable, purchasing a larger batch for storage gives further peace of mind and spreads the cost further, providing of course that the storage conditions are appropriate.

Interpretation of the microbiology results as CFU/g (colony forming units/gram) for moulds, yeasts and Thermophillic actinomycetes is not difficult. As a rule of thumb the lower the CFU count the better. Whilst a very low mould or yeast count (<10-100) should not usually cause concern, more consideration of the merits of a batch of forage should be triggered by a CFU count that reaches 1000-10,000. Certainly if any Aspergillis species of mould are identified the alarm bells should be ringing. Aspergillis Fumagatus has particular association with respiratory disease including ‘Farmers Lung’ in humans.

Storage

A suitably sized storage area will allow storage of a good-sized batch of your chosen forage giving consistency through the season. It makes financial sense for the welfare of racehorses to make adequate provision for a good-sized storage area. Third party storage is also sometimes an option where this is not available on site.

Forage merchant or farmer?

A good working relationship with one or more farmers or forage merchants is essential to be able to consistently buy good hay. They need to know what you want to buy and you need to be able to rely on them to provide a high quality product through the season.

Forage merchant Robert Durrant stands by the principle that “A good forage merchant should be able to supply a trainer with the same high standard of hay for much if not all of the season”.

He adds that in his opinion “American hay English hay or haylage are all good options when they have been made well and the quality is high, but the quality of the American hays are consistently more reliable.”

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

The nutritional contribution made by forage should complement that made by the concentrate feed. Most racing rations are high in energy, high in protein and low in fibre. Therefore a suitable forage needs to be contrastingly high in digestible fibre with a limited level of energy and protein. However, where you have sourced early cut hay or haylage that is more digestible and higher in energy and protein, the concentrate feed intake should be adjusted to account for this. This will help to avoid the issue of over feeding of energy or protein. An excess of energy can result in undesired weight gain or over exuberance, whilst an excessive intake of protein at the very least increases the excretion of ammonia, which is a respiratory irritant. Whilst it is important to know the calcium and phosphorus content of forage, the trace mineral content is less significant as the concentrate feed will meet the majority of the horse’s requirement. The exception to this, however is where a batch of forage is identified as having a severe excess of one particular element, e.g. Iron which can reduce the absorption of copper.

Much emphasis is placed on finding an optimum concentrate feed and associated supplements, to enhance the diet of horses in training. The same emphasis should ideally be placed on a trainer’s choice of forage. Forage can so easily make or break the best thought out feeding plan.

Nutritional Ergogenic aids for horses - boosting performance

No doubt we are all aware of the plethora of dietary supplements that are now available and that are promoted as offering clear and profound benefits to our horses’ health, general well being and performance. In the latter category are the so-called ergogenic aids. So what are they, and do they work?These are the questions that this article aims to address.

Dr Catherine Dunnett (01 July 2007 - Issue Number: 4)

By Dr Catherine Dunnett

No doubt we are all aware of the plethora of dietary supplements that are now available and that are promoted as offering clear and profound benefits to our horses’ health, general well being and performance. In the latter category are the so-called ergogenic aids. So what are they, and do they work? These are the questions that this article aims to address.

DEFINITION

Ergogenic is defined as ‘work producing’. An ergogenic aid is therefore some system, process, device or substance than can boost athletic performance in some fashion, such as speed, strength or stamina. Broadly speaking there are five categories of ergogenic aids: biomechanical, physiological, pharmaceutical, psychological, and nutritional.

From an athletic perspective ergogenic aids may - enhance the biochemical and therefore physiological capacity of a particular body system leading to improved performance,

alleviate the psychological constraints that can limit performance

accelerate recovery from training and competition.

This article will focus upon the use of nutritional supplements that are marketed or currently being researched for their efficacy in improving athletic performance in horses.

HOW DO THEY WORK?

In principle nutritional ergogenic aids can enhance exercise performance in horses in a variety ways, depending on the nature of the particular supplement. For example an ergogenic aid might -

Enhance the lean mass of a horse by reducing body fat content whilst maintaining muscle mass, leading to an improved power to weight ratio

Improve the ability to counter lactic acid production or accumulation – producing a slower fatigue process in muscle

Increase muscle mass – resulting in increased power or strength

Increase the transport of oxygen around the body

Improve the efficiency of utilisation of body fuels such as fat, glucose and glycogen

Increase the storage of fuels within the body

Enhance the storage and utilisation of high-energy phosphates used in the early stages of fast exercise

WHAT’S ON THE MARKET?

A vast array of supplements are promoted as being effective ergogenic aids to the training and racing of horses. The table below offers an overview of the global ergogenic aids ‘catalogue’ but is by no means intended to be an exhaustive list.

Ergogenic effects in horses and humans for dietary supplements marketed for use in performance horses

Proven* beneficial effect in horses Proven* beneficial effect in humans but not horses

No unequivocal ergogenic effect in either species

ß-hydroxy-ß-methylbutyrate (HMB) Creatine Gamma-oryzanol

Carnitine Dimethylglycine (DMG)

Trimethylglycine (TMG)

Ribose

Chromium

Stabilised oxygen

Ubiquinone (Co-enzyme Q10)

Branched chain amino acids (BCAA)

Prohormones

* Based on data produced from scientific trials, rather than anecdotal evidence.

Creatine

Many of us will have heard of creatine in the context of nutrition and sport. It has been the great success story, efficaciously and financially, within the sports nutrition sector from the 1990s to the present. In 2004, for example, gross revenue from creatine supplement sales to sports people within North America alone was estimated at $400 million.

This success largely stems from the fact that, unusually, it is a supplement that works! Admittedly, its effectiveness varies across different sporting disciplines. It has proven especially beneficial in sporting activities of comparatively short duration, such as the athletic disciplines of sprinting and jumping, but also in sports that require very high levels of power production as in rowing, swimming and track-based cycling.

Creatine accomplishes this performance enhancement, firstly by elevating the levels of high-energy phosphates, ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and PCr (phosphocreatine), stored in muscles. Secondly, creatine can enhance the effect of training; i.e. it boosts the responsiveness of the muscles to stimuli generated by training. This is often observed as increased muscle mass that arises from elevated production of the major muscle protein myosin and from enhanced levels of localised growth factors.

The benefits of creatine supplementation in training and competition have not passed the equine world by, and a number of products are marketed specifically for horses. Unfortunately however, despite the positive claims made for these equine products they are not supported by scientific evidence. Indeed the opposite is the case. Sewell and co-workers in the UK and Essen-Gustavssen’s group in Sweden have conducted three rigorous placebo-controlled studies in horses.

No positive effects of creatine supplementation on performance were found when parameters including time-to-fatigue, high-energy phosphate depletion and lactic acid production were measured. The underlying cause for lack of efficacy in horses is due to poor absorption of creatine from the equine gut, leading to inadequate levels being attained in the muscles.

Even if a strategy could be devised to deliver creatine effectively to the muscle, some researchers are of the opinion that there would still be no effect. They form this view on the basis that in comparison with humans the horses is an elite athlete wherein the level of creatine in equine muscle is at or very near to the physiological upper limit.

Carnitine

Carnitine is another well-known dietary supplement widely marketed as an ergogenic aid in human sports nutrition and within the equine industry. The role of carnitine in exercise in humans and horses has been researched for almost 20 years. The biological actions of carnitine that make it central to exercise include:

Directly: transport of fats into muscle mitochondria where they can be used aerobically (oxidised) to generate ATP

Indirectly: increase aerobic utilisation of glucose to produce ATP

Indirectly: reduce lactic acid production (acidosis)

Some research does indicate a positive effect of carnitine supplementation on exercise performance in human athletes, however there are other studies that seem to indicate the opposite.

Conflicting research results have also been found for horses. Studies carried out by Foster and Harris in Newmarket during the 1990s showed that dietary supplementation could increase carnitine levels circulating in the blood, but did not appear to affect the levels in the muscles.

In 2002 Rivero and his fellow researchers at the University of Cordoba conducted a placebo-controlled study into the effect of carnitine supplementation in 2-year-old horses when used in conjunction with an intensive 5 week long training programme. Improved muscle characteristics were seen in the carnitine-supplemented group of horses, including a 35% increase in the proportion of fast-contracting (type IIA) muscle fibres, a 40% increase in the number of capillaries supplying blood to the muscle and an 11% increase in the level of glycogen stored in the muscle. After a let down period of 10 weeks most of these improvements were reversed. It was concluded that carnitine supplementation enhanced the training effect on muscles and that this could improve performance.

Despite the large number of studies conducted over the years the balance of evidence does not yet allow a consensus to be reached on whether carnitine improves performance in horses (and humans) or not. Of course this does not rule out a beneficial effect, and Rivero’s study would seem to be encouraging.

Gamma-Oryzanol

Gamma-oryzanol is not as the name implies a single substance, but is a mixture of chemicals, mainly ferulic acid esters, derived from rice bran. It has been popularised as a potent anabolic agent, i.e. a substance that promotes muscle growth leading to increased strength and speed. Gamma-oryzanol has been employed in equine and human athletes in the belief that it elicits increased testosterone production and stimulation of growth hormone. To date there is no published research describing the effects of gamma-oryzanol on exercise performance in horses, so in an effort to judge its potential efficacy we have to draw upon comparative studies in humans and other animals.

Efficacy for gamma-oryzanol is debatable, as it is poorly absorbed from the digestive tract. What is more when given to rats, contrary to popular belief, it is reported to actually suppress endogenous growth hormone and testosterone production. Research carried out in humans fed 0.5g per day of gamma-oryzanol showed no improvement in performance, nor indeed any change in the levels of testosterone, growth hormone, or other anabolic hormones even after 9 weeks of supplementation. Thus in summary, no scientific evidence exists to support the anabolic effects ascribed to gamma-oryzanol.

Dimethylglycine (DMG) and trimethylglycine (TMG)

Both DMG and its precursor TMG cannot be regarded as new supplements having been researched briefly in the late 1980s with a single research report being published.

Rose and colleagues at the University of Sydney’s veterinary department looked into the potential benefit of DMG on heart and lung function, and lactic acid production in Thoroughbreds during exercise. In this placebo-controlled trial DMG was fed twice daily to a group of thoroughbred horses that underwent a standardised exercise test at varying intensities before and after supplementation with DMG or the placebo. On completion of the trial it was concluded that DMG produced no measurable improvement in any of the parameters, and that it exerts no beneficial effects on heart and lung function or lactic acid production during exercise. Warren and co-workers following experimental evaluation of TMG as an ergogenic aid came to a similarly negative conclusion.

ß-Hydroxy-ß-methylbutyrate (HMB)

HMB is one of the few ergogenic aids available for use in performance horses that is supported by at least some credible science. Significantly, research developing and validating the use of HMG in horses (and farm animals) was instigated and carried forward over a number of years at Iowa State University, USA, and the concept and methodology are protected by US patents. HMB is a metabolite of leucine, one of the so-called branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), that are themselves often touted as ergogenic aids, although there is no convincing evidence to support such a claim.

Research seems to indicate that HMB supplementation when employed in conjunction with an effective training regime can benefit equine performance in a number of ways:

Enhance muscle development and increase lean muscle mass and strength by reducing the proportion of energy needed for exercise that is derived from protein and increasing the proportion derived from fat.

Reduce muscle damage (catabolism) during and after exercise and accelerate muscle repair. Some research suggests that HMB is a structural constituent of muscle cells that is destroyed under the physiological stress of exercise.

Increase aerobic capacity (oxygen utilisation) in performance horses by increasing both haemoglobin and the proportion of red blood cells in the blood (haematocrit).

When HMB use was evaluated in practice under real racing and training conditions it appeared to reduce muscle damage, and to improve oxygen use by the muscles and overall performance.

NEW DEVELOPMENTS

Ribose

Ribose is a potential new dietary ergogenic aid that began to be studied in 2002. It is a sugar that is the central component of ATP. As ATP stores are depleted during intense exercise in horses, it was thought that supplementing the horses’ diet with ribose might lessen the loss of ATP during exercise and enhance its regeneration during recovery. Kavazis and his colleagues at the University of Florida conducted two placebo-controlled studies in Thoroughbreds. In these studies ribose was fed twice daily as a top dressing for two weeks to a group of trained horses. The data from these two studies was contradictory and thus no conclusions can be easily drawn. However, two studies in humans have shown no positive effect of ribose supplementation on exercise performance. The balance of available evidence therefore suggests that ribose provides no ergogenic benefit in performance horses.

Bioavailable stabilised oxygen

An unusual ergogenic product has recently appeared that purports to be a bioavailable supplementary source of oxygen. In simple terms, it is water that is apparently treated by a sophisticated electrical process so that it becomes a super-saturated solution of oxygen. It’s described as containing about 20,000 times more oxygen than that found in average tap water. As yet, there appears to be no convincing scientific evidence for this type of product, and what is more the explanation of its action does not seem to be physiologically credible.

It is suggested that this bioavailable oxygen is absorbed from the stomach and intestine into the blood stream, however these tissues have not evolved for this purpose unlike the lungs. Even if we assume that all the oxygen from e.g. (100 mL) was taken up into the blood, the added benefit would be very small; 100 mL is roughly equivalent to 20 litres of oxygen. In comparison, an average horse exercising at racing speeds breathes in more than 2000 litres of air (420 litres of oxygen) every minute and the muscles use 75 litres of oxygen over the same period. We should also remember that for a normal healthy horse the blood is 98% saturated with oxygen.

WHERE NEXT?

The future direction for nutritional ergogenic aids is extremely difficult to predict as any new developments are likely to mirror advances in our detailed understanding of the basic biochemical and physiological processes that underpin exercise performance. In the past, much of the impetus for equine research in this area developed from human sports nutrition and this is likely to continue in the future. A closing comment to put all of this information into context would be that whilst one should always seek a feasible mechanism of action and proof of efficacy for new products, small numbers of horses used in trials and difficulties in measuring ‘performance’ means that science will not always come up with the absolute answer.

Forage - so much more than just a filler

Too often thought of as just a ‘filler’, or occupational therapy to while away the time between hard feeds, forage is worth so much more than that. Simply feeding an inadequate quantity of forage, or choosing forage that has an inappropriate nutrient profile, or is of poor quality can have a negative impact both on health and performance in racehorses.

Dr Catherine Dunnett (European Trainer - Issue 18 - Summer 2007)

Too often thought of as just a ‘filler’, or occupational therapy to while away the time between hard feeds, forage is worth so much more than that. Simply feeding an inadequate quantity of forage, or choosing forage that has an inappropriate nutrient profile, or is of poor quality can have a negative impact both on health and performance in racehorses. Inappropriate choice of forage and its feeding can easily lead trainers down the slippery slope towards loose droppings and loss of condition.

Forage can also have a significant impact on the incidence and severity of both gastric ulcers and respiratory disease, including inflammatory airway disease (IAD) and recurrent airway obstruction (RAO).

When choosing forage the main elements to consider are

• Good palatability to ensure adequate intake • Adequate digestibility to reduce gut fill

• Fitness to feed to maintain respiratory health

• A profile of nutrients to complement concentrate feeds

FORAGE CAN ONLY BE GOOD WHEN PALATABLE

Palatability is a key issue, as even the best forage from a quality and nutritional standpoint is rendered useless if the horses do not eat sufficient quantities on a daily basis. Palatability is a somewhat neglected area of equine research and so we largely have to draw on practical experience to tell us what our horses like and what they don’t. Some horses appear to prefer softer types of hay, whilst others prefer more coarse stemmy material. Many horses readily consume Haylage, whilst some trainers report that other horses prefer traditional hay. Apart from the physical characteristics, the sugar content of hay or haylage may affect its palatability. Forage made from high sugar yielding Ryegrass is likely to have a higher residual sugar content compared with that made from more fibrous and mature Timothy grass. Some interesting research carried out a few years ago by Thorne et al (2005), provided some practical insight into how forage intake could be increased in the reluctant equine consumer.

This work reported that the amount of time spent foraging (which will increase saliva production), was increased when multiple forms of forage were offered to horses at the same time. From a practical viewpoint this can be easily applied in a training yard and it should help to increase the amount of forage consumed. For example, good clean hay could be offered together with some haylage, and a suitable container of alfalfa based chaff or dried grass all at the same time.

A Healthy Intake Racehorses in training often eat below what would be considered to be the bare minimum amount of forage to maintain gastrointestinal health. Whilst sometimes this is due to the amount of forage offered being restricted, in other instances it is because the horses are limiting their own intake. This may be due to either their being over faced with concentrate feed, or due to unpalatable forage being fed. Establishing a good daily intake of forage during the early stages of training and then maintaining the level through the season is important. Typically the absolute minimum amount of forage fed should be about 1% or 1.2-1.5% of bodyweight for hay or haylage, respectively.

This equates to 5kg of hay or a rounded 7kg of haylage for an average sized horse (500kg). The weight of haylage fed needs to be greater than that of hay due to the higher water content of the latter. Intake of haylage needed to achieve a similar dry matter intake to 5kg of hay Moisture Dry Matter Weight of forage % Increase above hay Hay (Average) 15% 85% 5kg Haylage 1 30% 70% 6kg 20% Haylage 2 45% 55% 7.5kg 50% The dry matter of haylage needs to be consistent to allow a regular intake of fibre and reduce the likelihood of digestive disturbance or loose droppings.

Ideally trainers should be aware of any significant change in dry matter, so that they can adjust the intake accordingly. Forage intake is restricted in racehorses to firstly ensure that a horse consumes adequate concentrate feed to meet their energy needs and requirement for vitamins and minerals within the limit of their appetite. Secondly, the amount of forage fed is restricted in order to minimise ‘gut fill’ or weight of fibre and associated water in the hindgut, as this will restrict their speed on the racetrack. BUT… inadequate amounts of forage in a horses’ diet has such a negative effect on health that the minimum amount fed must be kept above recognised ‘safe limits’.

Choosing an early cut forage that is less mature and with more digestible fibre means that the ‘gut fill’ effect is lessened. In addition, horses can always be fed more forage during training with the daily quantity being reduced (within the safe limits) in the few days before racing where this is practical.

FITNESS TO FEED

Quality of forage, in terms of its mould, yeast and mycotoxin load, can have a major impact on respiratory health. A recent Australian report (Malikides and Hodgson 2003) highlighted the cost of inflammatory airway disease (IAD) in horses in training, in terms of loss of training time and of potential earnings, together with the associated cost of veterinary treatment. They estimated from their study group that in Australian racing up to 33% of horses in training can have lower airway inflammation, yet show no overt clinical signs. Type and therefore quality of forage, as well as the quality of ventilation were singled out as the most significant risk factors in the development of IAD.

Forage is potentially a concentrated source of bacteria, mould spores and even harvest mites. Hay that has heated during storage, or that has been bailed with a high moisture content is likely to provide a greater load of these undesirable agents that can harbour substances that promote airway inflammation, such as endotoxin. Purchasing good quality and clean forage from a respiratory perspective will certainly reduce the pressure placed on young racehorses’ respiratory systems.

However, how does one achieve this?

• Microbiological Analysis – the price paid for a microbiological analysis of a prospective batch of hay is a worthwhile cost when the consequences of poor hay are considered.

Assuming the analysis is favourable, purchasing a larger batch for storage gives further peace of mind and spreads the cost further, providing of course that the storage conditions are appropriate. Interpretation of the microbiology results as CFU/g (colony forming units/gram) for moulds, yeasts and Thermophillic actinomycetes is not difficult. As a rule of thumb the lower the CFU count the better. Whilst a very low mould or yeast count (<10-100) should not usually cause concern, more consideration of the merits of a batch of forage should be triggered by a CFU count that reaches 1000-10,000. Certainly if any Aspergillis species of mould are identified the alarm bells should be ringing.

Aspergillis Fumagatus has particular association with respiratory disease including ‘Farmers Lung’ in humans.

• Storage –A suitably sized storage area will allow storage of a good-sized batch of your chosen forage giving consistency through the season. It makes financial sense for the welfare of racehorses to make adequate provision for a good-sized storage area. Third party storage is also sometimes an option where this is not available on site.

• Forage merchant or farmer - A good working relationship with one or more farmers or forage merchants is essential to be able to consistently buy good hay. They need to know what you want to buy and you need to be able to rely on them to provide a high quality product through the season. Newmarket based forage merchant Robert Durrant stands by the principle that “A good forage merchant should be able to supply a trainer with the same high standard of hay for much if not all of the season”. He adds that in his opinion “American hay English hay or haylage are all good options when they have been made well and the quality is high, but the quality of the American hays are consistently more reliable.”

PRO’S AND CON’S

Hay from colder climates e.g. UK, Ireland commonly used quality can be variable usually palatable economical Haylage. Usually clean dry matter can be variable Fermentation inhibits mould growth Need to feed more than hay Feed value often higher May need to adjust hard feed Usually palatable Beware of punctured bales Newmarket trainer James Eustace has used big bale haylage for many years he says “I found it increasingly difficult to reliably source good clean English hay. I am very happy with the haylage, as it is pretty consistent and it provides the dust free option that I wanted.”

Hay from warmer climates e.g. USA / Canada usually very clean May need to adjust hard feed Feed value often higher Premium price Usually palatable Newmarket trainer Ed Dunlop appreciates the advantages of using more than one forage source he says, "American hay gives us the consistent good quality that we need and the horses eat it well. Feeding it alongside other forage gives us the flexibility needed for different horses throughout the season." Alfalfa (High temperature dried or sun dried)

Good adjunct to forage (e.g 1-2kg) High intakes can oversupply protein and calcium Can be used as chaff Leaf fragments can add to dust High feed value & digestibility Less gut fill Many of Forage merchant Robert Durrants clients choose sun dried alfalfa as an extra treat for the horses he says “the horses get a large double handful daily as a treat and they love it.”

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

The nutritional contribution made by forage should complement that made by the concentrate feed. Most racing rations are high in energy, high in protein and low in fibre. Therefore a suitable forage needs to be contrastingly high in digestible fibre with a limited level of energy and protein. However, where you have sourced early cut hay or haylage that is more digestible and higher in energy and protein, the concentrate feed intake should be adjusted to account for this. This will help to avoid the issue of over feeding of energy or protein. An excess of energy can result in undesired weight gain or over exuberance, whilst an excessive intake of protein at the very least increases the excretion of ammonia, which is a respiratory irritant.

Whilst it is important to know the calcium and phosphorus content of forage, the trace mineral content is less significant as the concentrate feed will meet the majority of the horse’s requirement. The exception to this, however is where a batch of forage is identified as having a severe excess of one particular element, e.g. Iron which can reduce the absorption of copper. Much emphasis is placed on finding an optimum concentrate feed and associated supplements, to enhance the diet of horses in training. The same emphasis should ideally be placed on a trainer’s choice of forage. Forage can so easily make or break the best thought out feeding plan.

Feeding during early training - how to minimise problems

Most of the current crop of 2yo’s will now have been broken and are in the early stages of training proper in readiness for the forthcoming flat racing season. This period brings with it numerous problems for trainers and their staff, such as horses with high muscle enzymes, episodes of tying up, respiratory infections, various lamenesses and other skeletal problems or simply over exuberance.

Catherine Dunnett (European Trainer - issue 17 - Spring 2007)

Most of the current crop of 2yo’s will now have been broken and are in the early stages of training proper in readiness for the forthcoming flat racing season. This period brings with it numerous problems for trainers and their staff, such as horses with high muscle enzymes, episodes of tying up, respiratory infections, various lamenesses and other skeletal problems or simply over exuberance.

Whilst such issues have many contributory factors, a good basal diet, with carefully selected extras can help to minimise some of these niggling problems. Overfed horses can become fat or too excitable During breaking, and pre- and early training the emphasis from a nutritional perspective should be on adequate but not excessive energy intake, whilst ensuring that a balanced diet is provided in terms of vitamins, minerals and quality protein. An overfed horse becomes either fat and so difficult to slim down for racing, or badly behaved and excitable, and thus more prone to injure itself or its rider. To avoid excitability, good quality hay or haylage fed in increased amounts will not only help to reduce the reliance on concentrate feeds, but may also reduce ulceration, especially in horses in their first season of race training. There are several concentrate feeds manufactured specifically for horses in early training or during a ‘lay off’ period. These are generally lower in energy than racing feeds, but still ensure an adequate intake of quality protein for young horses and provide a more concentrated source of vitamins and minerals, given that the intake of feed can be quite low at this time. Sometimes a more economical alternative to these tailored feeds would be a good quality low energy mix or cube, manufactured for the mainstream horse market.

However, reassurance should always be sought from the manufacturer concerned on the suitability of the main ingredients, including the protein and fibre sources and vitamin and mineral level for a horse in pre or early training. An further advantage of these two concentrate feed types for this stage of training, is that the energy provided is derived largely from digestible fibre and sometimes oil, with less emphasis on cereal starch. This is potentially beneficial for behaviour, and also for horses with a predisposition for tying-up or ‘set fast’. Not every raised muscle enzyme is a ‘set fast’ Raised blood levels of the muscle enzymes AST (aspartate aminotransferase) and CPK or CK (creatine kinase) are common place during early training. These enzymes are present at much higher levels in muscle cells than other tissues and therefore their leakage into the blood is considered indicative of muscle damage. The complication is that although muscle damage can result from an ongoing metabolic issue such as tying up, it may also occur as the result of transient over exertion. High AST and CK’s in blood are not always an indication of a horse having tied up and some horses that exhibit these blood results in the early stages of training will often work through it as training progresses.