International Horse Movement - under the spotlight

At the annual European Horse Network / MEP’s Horse Group Conference in Brussels

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen opened the conference held in Brussels 16 November 2021 with a message of support. Paull Khan, secretary-general of the European and Mediterranean Horseracing Federation, then spoke on international horse movement and, in specific, in the context of the three political and legal factors of Brexit, the EU Animal Health Law and the review of Animal Welfare regulations, particularly the Transport Regulation.

Khan looked at things primarily through a “thoroughbred lens,” but also included other relevant equine sectors. Explaining why horse movement is so important to our sector, Khan pointed out, “Horse racing is not only a serious sport, it is a serious business. We estimated last year that the economic impact of racing in Europe is some €23bn per annum, and the sector directly employs over 100,000 people, mainly in rural areas.

“Horse racing is widespread across the EU. Seventeen of our European and Mediterranean Horseracing Federation members are EU member states—the same for our sister organisation, the European Trotting Union; and movement of thoroughbreds is central to this industry.”

While other agricultural animals will typically only move internationally once, if at all, usually for slaughter, horses, particularly racehorses and sports horses, frequently move between countries for reasons other than slaughter. Khan stressed the importance of repeating this to those outside our sector: “As legislators may have in their minds ‘travel for slaughter,’ when they think of international travel of horses and other animals.” Almost 90,000 equines in a normal year travel internationally within, or to and from, the EU; and it is estimated that nearly 60% of these movements are not for slaughter.

“For thoroughbreds, it starts at the very beginning—at their conception,” said Khan. “So the movement of mares to visit stallions is essential. And it is vital, for the improvement of the breed and in order that Europe retains its competitive pre-eminence in this area, that mare owners are able to select from a broad panel of stallions, which may be based in other countries. There are growing concerns in the Stud Book community about inbreeding. Limiting the geographical footprint is an obvious way to restrict that gene pool.”

He went on to point out that during the horse’s racing career, the better it is, the more likely it will travel internationally to contest the best races. “Again, this process is critical to the improvement of the breed. The performances of a racehorse within any given country are only truly validated when that horse is tested by racing the best in other countries.”

Moving on to the issues posed by Brexit, Khan reminded us that the three countries with the largest thoroughbred industries—France, Ireland and Great Britain—had relied on the former Tripartite Agreement to allow for largely free and unrestricted travel within this bloc. There were over 26,000 international movements of thoroughbreds annually between these three nations alone. Now, movement between Great Britain and EU countries requires blood tests, the involvement of official vets for health certification, further health-check on entry, pre-notification of the movement, both outbound and return, Customs paperwork (four sets for a return trip) and the payment of value added tax. “The burden in terms of cost, time and hassle of moving a horse has risen starkly,” Khan illustrated.

“There are also welfare issues here,” he continued. “World Horse Welfare tell me that the requirements are impacting compliant traffic but not non-compliant traffic. We have heard of people choosing to send horses from France, destined for Britain by the long sea route to Ireland, then traveling up to Northern Ireland and finally across to mainland Britain, all in order to avoid all this. Clearly not in the horses’ welfare interests. And we know of delays of several hours at Border Control Posts (BCPs) and of horses—most recently a nine-month-old foal, which was sent back to the UK on its own because of a technicality of the paperwork.”

What is frustrating is that so much of this is unnecessary. Khan said, “Taking the health certification requirements first, they are not serving to solve any existing bio-security problem—there were no issues arising out of the movement of horses to and from the UK throughout the 50 years before Brexit. But putting that aside, the requirement to complete lengthy paperwork is unnecessary, given the existence of a digital alternative.

“And secondly, in respect of the VAT, the vast majority of racing and sport horse movements are return journeys—the horse travels to compete, or breed, and then returns. But even though VAT is not ultimately payable in the case of temporary movements, there is the need for connections of the horse to pay the VAT, or put up security against its value and then reclaim it. This is time consuming, not only for the connections of the horses but also for the revenue officials collecting the money who then have to spend time in repaying that money to the connections when the horse has gone home. Repayments are reportedly typically taking five months from some countries. This is a pointless waste of time and effort for horsemen and officials alike.”

What effect has all this had on movement numbers to and from Great Britain? “It’s very difficult, of course, to split the effect of COVID from that of Brexit; but what we can see very clearly is that, in combination, Brexit and COVID have had a downward impact on thoroughbred movements,” Khan reflected.

“It is clear that racing movements, i.e. international runners, suffered badly in the first year of COVID, roughly halving from 2019, whether between Britain and the EU or the rest of the world. It is true that, since Brexit, rather than seeing a further deterioration, we have witnessed a recovery. Racing movements this year, despite Brexit, have been higher than in 2020—24% higher to and from the EU, and 59% higher to and from the rest of the world. But, while we must be optimistic that the worst effects of COVID are behind us, we cannot be so confident about Brexit. We just don’t know how owners’ and breeders’ behaviour will be modified in future years by the stark reality of their experience in this, ‘Year One’. Now that they know what the final bill added up to and how long it took for them to receive their VAT repayments, it is not unreasonable to surmise that they may choose not to repeat the exercise in the future.”

Even given this year’s recovery, he noted that international runners between Britain and the EU have fallen by one-third against 2019 levels, and those with the rest of the world are down by 13%.

“This means that EU owners and trainers have had fewer opportunities to test their horses against those in Britain, and races on both sides of the water have been weakened, both in their appeal to the public and as international testing grounds.

“This could have a long-term damaging effect in an area where Europe leads the world. No fewer than 38 of the world’s top 100 races are run in Europe—more than Asia which has 23, Australasia 26 and the Americas 13. I mentioned the economic impact of European horse racing over €23bn per annum; much of this is linked to the quality of the races that are run here.”

“Tracing a very different pattern have been non-racing movements (excluding Ireland), which were far more resilient to COVID than were racing movements but which have suffered post-Brexit in a way that racing movements have not. Movements for breeding and other purposes outnumber racing movements by around six to one.

“Looking at movements between Britain and Continental EU—we don’t have these figures for Ireland because Britain and Ireland share a common Stud Book—we see they have more than halved, from 4,283 to 1,964. An indication of the ‘Brexit effect’ can be inferred from the fact that movements between Britain and the rest of the world only reduced by 13%, despite COVID.

“Non-racing movements to and from Ireland have held up remarkably well, being within 4% of 2019 levels. Overall, thoroughbred journeys between Britain and the EU are one-third down on two years ago.

“This isn’t just affecting racing. The European Equestrian Federation have told me that they have seen reduced numbers, both of British competitors at European events and Europeans travelling to Britain. And, taking the perspective of Ireland, we see a very similar picture. Non-racing movement of thoroughbreds between Ireland and the rest of the EU has fallen from 3,951 to 2,407—a 39% fall.

“Overall movements to and from Ireland would appear to be down by one-quarter—less, therefore, than the one-third fall to and from Britain. As in Britain, racing movements have shown a recovery this year, whereas non-racing movements, except those too and from Britain which have been static, have continued to fall.”

Animal Health Law was the next major issue to be examined in detail by Khan, although as he pointed out, the AHL has only applied since April; and member states are at different stages of their practical implementation. “In brief, it is too soon to gauge its impact on horse movement,” he warned.

“The new requirements for the registration of operators and establishments, the registration of the place where a horse is habitually kept, the need to record all arrivals and departures, etc., will create additional work. And it could be argued that the problems these measures are being brought in to address are largely absent in the race and sport horse sectors; and they come at a time when the equine sector is already reeling from the impact of COVID.

“What I would say, however, cautiously, is that, from the soundings I have been making, my impression is that, at least in our sector, there are no widespread concerns over the impact of this new legislation per se on horse movements.”

He then moved on to the third piece of legislation, the Animal Transport Regulation. “Here, we’re concerned that some of the recommendations of the European Parliament’s Committee of Inquiry, ANIT, do not eventually become law.”

Subsequent to the Conference, ANIT produced its final report in early December, and Khan has provided us with an update on the current situation.

“We are pleased that a number of the points we and our sister organisations made appear to have been heeded. There was the threat of a blanket ban on transport of live horses to third countries, but this has gone, as has a requirement for a vet to be present at all loadings and unloadings. The fact that mares need to travel to visit stallions in order to conform with the global ban on artificial breeding methods in the thoroughbred world has also been acknowledged. It would seem, too, that the hard-won derogation from the journey limit of eight hours has been retained.

“What we need to concentrate on in the coming months, and make representations to the Commission as appropriate, includes the proposed ban on travelling horses outside of the range -5 degrees to +30 degrees, and ensuring that travel of horses by horsebox on roll-on/roll-off ferries is differentiated from travel by sea vessel. I’m sure our colleagues in the breeding world will also want to ensure that there is a derogation from any ban on travelling unweaned foals even if they are accompanied by their dams, and the proposed ban on animals travelling when in the last third of gestation.”

Returning to the questions posed at the conference, Khan provided advice on how decision makers can support the industry. “Taking Brexit first, it is the unanimous view of all 26 EMHF member countries, that an easing of movement between the EU and the UK will benefit the whole of the European thoroughbred industry. We need to address avoidable areas of friction, which are only likely to worsen when the UK introduces its own BCPs to mirror those in EU countries. And I come back to the two things I mentioned earlier: unnecessary paperwork and unnecessary VAT payments. We’re hopeful that the newly formed Sanitary & Phytosanitary Committee can help here and we hope that there will be some expert input from the equine sector on that Committee.”

He also called for a commitment to embrace digital technology to replace the current antiquated paper-based systems. “The use of equine e-passports for equine identification is already providing welfare and health benefits through the eradication of tampered and fraudulent passports and improved traceability through real-time validation and audit trails. These digital passports, which have been built by both the sport horse and racehorse sectors—all Thoroughbreds in Ireland and Britain have them—comprise identity, vaccination and veterinary records, movement and ownership. We need governments to work with us to enhance this existing technology through interoperability with the systems of relevant government agencies: vets, Customs, revenue, etc. This will reduce cost, reduce time, reduce the risk of error and fraud. It will also cut down waiting times and workloads at Border Control. Vets at BCPs have many other, far more pressing tasks from which checking high health horses is currently just a distraction; and this can be stopped.

“Of course, acceptance of e-passports from selected third countries will be necessary to address the Brexit issue, and current EU Law precludes this.

“More generally, we seek the introduction of a system which recognises that, where high health status of a horse population can be demonstrated, the regulatory burden imposed on the movements of such horses should be appropriately reduced. Such an evidence-led, risk-based approach— such as the High Health Breeding “HHB” concept, which the European Federation of Thoroughbred Breeders have advocated and is now being examined by the chief veterinary officers (CVOs) of Ireland, France, Germany and the Scandinavian countries, or the similar High Health Horse concept which the racing and sport horse sectors proposed to the Commission some four years ago—would make best use of stretched veterinary and administrative resources, [would] give much-needed respite to the equine sector and benefit horse welfare.

“We also call upon the revenue authorities in member states and the UK to adopt the flexibility, which it is within their gift to do, in agreeing sensible exemptions from the requirement to make payments in relation to value added tax in the case of temporary movements of horses. The racing industries in the most affected countries are all engaging with their respective revenue authorities on this question. Support from MEPs would be very valuable.

And on the Transport Regulation, we ask that our legitimate concerns are taken into account and that we avoid additional provisions in law which would unnecessarily seriously damage the equine sector further.”

Khan concluded on a positive note by pointing out, “I’d just like to underline that those in the racing and breeding community are passionate about their horses. We have long worked closely with World Horse Welfare and others, and we are fully behind their efforts and those of MEPs towards improving conditions for horses.”

MOVEMENT OF HORSES 2021 TABLES

GB / IRE BREEDING MOVEMENTS INFERRED FROM COVERING STATISTICS

Click to view the tables:

OUTBOUND MOVEMENTS FROM GB

GB-TRAINED RUNNERS (RACE STARTS) IN EU/SWI & RoW

RACING MOVEMENTS - INBOUND MOVEMENTS TO GB

NON-RACING MOVEMENTS - Excludes movements between Great Britain and Ireland

The challenge of transport - the practical considerations for transporting horses

CLICK ON IMAGE TO READ ARTICLE

Des Leadon (16 July 2009 - Issue Number: 13)

The challenge of transport - the practical considerations for transporting horses

The after-effects of travel on racehorses has vexed trainers for decades. Short-distance transport of racehorses is, as every trainer knows, almost always of very little consequence. Longer distance transport presents a much greater challenge and months of work and planning can be undone in the course of a few hours.

Des Leadon (European Trainer - issue 24 - Winter 2008)

Picky Eaters - a common problem in horses in training

Poor appetite in horses in training is not uncommon, whether this is a transient problem following racing, or, more regularly, during training in particular horses.

Dr Catherine Dunnett (European Trainer - issue 24 - Winter 2008)

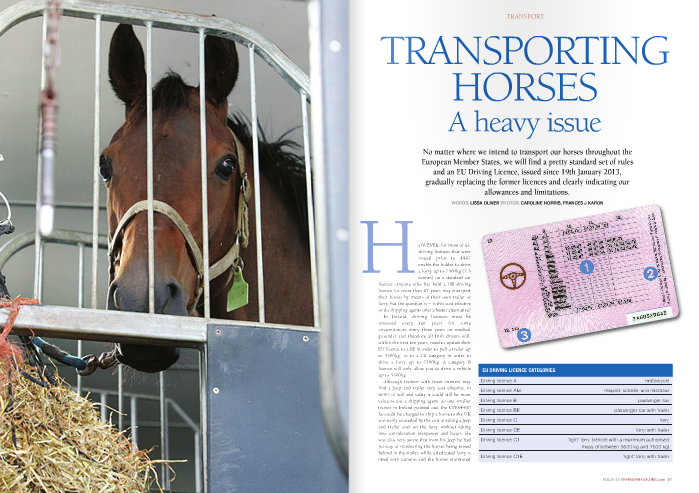

New European legislation could prove costly for racehorse transporters

The enforcement of new European legislation next spring may come as a costly blow to racehorse transporters. The regulation aims to safeguard animal welfare by radically improving conditions during transport, but the racing industry feels that existing standards are already sufficient and the innovations amount to only red tape.

James Willoughby (European Trainer - issue 14 - Summer 2006)

THE enforcement of new European legislation next spring may come as a costly blow to racehorse transporters. The regulation aims to safeguard animal welfare by radically improving conditions during transport, but the racing industry feels that existing standards are already sufficient and the innovations amount to only red tape.

The “Animal Welfare During Transport Regulation” was first drafted by the European Commission in November 2004, primarily with the desire to safeguard livestock being moved for slaughter. There have been countless horror stories involving these poor beasts, who are often subjected to shockingly cramped conditions and treated with little dignity. Racehorses, however, are another matter entirely, but the bill will have a knock-on effect unless an exemption clause is brought in.

Animal transporters (not racehorse transporters) undertaking journeys of over eight hours will be forced to fit satellite navigation systems into newly built vehicles from next year, while all vehicles must have the equipment from 2009. There is also a stipulation for air conditioning. Drivers and staff will need to achieve competency certificates. The total cost of improvements, upgrades and other compliance is thought to total up to £20,000 / €29,000 per vehicle. For both racehorse transport companies and private individuals, this will come as a serious financial blow. It is thought that the governments of Ireland and France will be lenient when it comes to enforcing these regulations. This is no surprise in the case of the former, given the long-standing desire to protect its racing industry for economic, social and political reasons. Britain, however, is another matter, and there are plenty who feel that the overzealous manner with which the detail of EU regulations are adhered to is to the country's detriment.

Kevin Needham, who runs BBA Shipping And Transport Ltd, feels that the needless astringency of the new rules will result in only one reaction. "Operators will ignore them," he said. "Bring a prosecution will be so difficult; there is much the authorities will need to prove. This is nothing but a source of irritation and annoyance." "Every horse box we build nowadays is different to the one before. The whole process is geared towards the operator. Whatever facility you want can be added, and the standard of boxes nowadays is a lot better than in the past. We are not driving lorries with cart springs around anymore, now we have modern chassis with air suspension."

According to Needham and other executives in the same sector, it behoves transporters to move racing and breeding stock with the greatest possible care already. "It matters to everyone who moves thoroughbreds that they get to the races in the best possible condition. Optimum performance depends on it, and our customers rightly will not stand for anything less." Merrick Francis of the Racehorse Transporters’ Association is optimistic that a differentiation will be made between racehorses and other livestock that will overt the situation. "It is still all up for consultation and interpretation by DEFRA [the department for environment, food and rural affairs] but there is reason for optimism that a practical solution can be found," he said.

The pivotal point of this situation is that the EU has listed the changes as 'regulations' rather than 'directives'. This allows the British government far less flexibility, though, according to the Racehorse Trainers’ Federation chief executive Rupert Arnold, they are doing what they can. "DEFRA is trying to be as flexible and helpful as possible. I think that we can find a way through this, but there are areas such as with competency certificates and the regulations applying to journey times and distances that need clarification," he said. One thorny issue of the new regulations is that of competency certificates, which will be required for both drivers and their assistants. Many transporters feel strongly that it is ridiculous to ask a box driver of 40 years experience to pass a test conducted by someone else with far less knowledge of the trade.

Furthermore, there are new controls preventing horses being transported below 0C and above 30C, but trainers who set off for the races early in the morning could not help but offend this stipulation. Most punitive of all is the rule that pertains to the angle of slope of a horse box's ramp which would immediately outlaw a huge number of existing lorries. Cathy McGlynn, the European consultant for the British Horseracing Board, is attempting to assuage these and other frustrations for the racing industry. And the good news is that she is making purposeful headway. "We have been working hard at this for four years, consulting with Rupert Arnold and Merrick Francis and the civil servants. Our dealings with DEFRA have been constructive," she said. "The chances are that domestic racehorse transporters will not be too hard hit, but those firms operating on the continent will have to comply. Details are still to be sorted out." McGlynn concurs with those who feel that the high standards of welfare common throughout the racing industry need no improving upon. Like Arnold, she is particularly frustrated at the rules pertaining to permissible temperature. "There is just no scientific basis for this regulation. If there were, it would be a different matter, but there is no proof of any welfare issue at temperatures outside those which they state." "In some parts of Europe, for example, it is below zero for half of the year. Introducing regulation that cannot be adhered to is futile," she said.

The fact is that this issue took horns from the disgraceful state in which horses for slaughter have been treated in countries such as Hungary and Poland. The International League For The Protection Of Horses and the RSPCA are entirely justified to have taken action over this issue, and the legislation is a step forward in this sphere. But penalising racehorse transporters seems invidious. Needham is particularly irritated by the intransigency of the EU to differentiate between the two situations. "It is a case of one size being made to fit all. The regulations are made from the meat-horse perspective. Nobody is going to jeopardise a Sadler's Wells filly with a foal at foot, for example," he said.

Furthermore, the directive is also looking for all loading ramps to have a 20 degree loading angle and for all boxes to have a minimum headroom of 75cm (roughly 30 inches) above the withers. There is no way that small operators can take on the significant extra expenditure to modify existing boxes, and most will choose to run the gauntlet. Racehorse transportation has taken a quantum leap forward in tandem with the increasing internationalisation of the sport. Gone are the days in which European horses were not in a fit state to compete at events such as the Breeders' Cup. And the awareness of optimum international travel, coupled with the great strides made in other equine sports, have had a knock-on effect in raising domestic standards. "Arthur Stephenson used to send his horses to Cheltenham and back (500 mile round trip) in a day, and horses can still travel long distances, get off the box and run well," Needham says. "Traffic is a bigger problem nowadays, however. Our boxes going to Ireland can get stuck on the A14 for hours. Forward planning can overt this to a degree, such as traveling at off-peak times where it is practical. There are always unforseen delays though. Finding a solution to awkward problems is a daily problem for transporters."

In addition to the new regulation, all horseboxes sold after May 1st 2006 are now fitted with Digital Tacographs, to record driver’s hours and from October 1st 2006 all horse boxes have to be sold with a “Euro 4” specification engine. “The idea behind the new specification engine is to reduce engine emissions even further” says George Smith of George Smith Horseboxes. “However, they’ve been cleaned up since 1990, the new specification is simply to reduce both Nitrous Oxide and soot this is impossible unless you use either an AD Blue System or exhaust gas recirculation”. The cost – approximately £3,000 (€5,000). Naturally, vehicle manufacturers are advising us to buy new boxes before the new regulations come into force!

Do horses suffer from jet-lag?

The consequences of jet lag for the equine athlete have become more relevant in recent times due to increased travel of performance horses across multiple time zones for international competition.

Barbara Murphy (European Trainer - issue 7 - Spring 2004)

The consequences of jet lag for the equine athlete have become more relevant in recent times due to increased travel of performance horses across multiple time zones for international competition. The effects of jet lag are significantly more detrimental for the professional athlete hoping to perform optimally in a new time zone. Before defining the implications of jet lag for the horse, it is first necessary to understand the effects of light on any mammalian system. Most all life on earth is influenced by the daily cycles of light and dark brought about by the presence of the sun and the continuous rotation of our planet around its own axis.

From the simplest algae to mammals, nearly all organisms have adapted their lifestyle in such a way that they organize their activities into 24-hour cycles determined by sunrise and sunset. For this reason, many aspects of physiology and behaviour are temporally organized into circadian rhythms driven by a biological clock. Thus, biological clocks have evolved that are sensitive to light and so enable physiological anticipation of periods of activity. Light is the primary cue serving to synchronize biological rhythms and allows organisms to optimise survival and adapt to their environment. An example of this environmental adaptation is clearly evident in the mare’s natural breeding season. As the number of hours of light gradually increases in the early spring, the mare’s reproductive system reawakens and within weeks is ready for conception.

With an 11 month, one week gestation period, horses have evolved to produce their young when the days are long and warm and the grass is green – the ideal environment for a growing animal and for a lactating mare with increased nutritional needs. However, we have interfered with nature’s design. With the creation of a universal birthday for Thoroughbred horses of January 1st and the economic demands to produce early foals for sale as mature yearlings, we have succeeded in altering the mare’s natural breeding season through use of artificial lighting programmes. A 200-watt light-bulb, in a 12-foot by 12-foot stall, switched on from dusk until roughly 11:00 pm nightly and beginning December 1st, is sufficient to advance the onset of the mares reproductive activity such that she should be ready to be bred by February 15th, the official start of the breeding season. From this, it is clear that light can control seasonal rhythms. What is more important in relation to jet lag is that light also closely regulates daily, or circadian rhythms. These circadian rhythms include changes in body temperature, hormone secretion, sleep/wake cycles, alertness and metabolism. A disruption of these rhythms results in jet lag.

It can be defined as a conflict between the new cycle of light and dark and the previously entrained programme of the internal clock. The first step to understanding jet lag is to examine the workings of the biological clock and the extent to which the daily cycles of light and dark can control physiological processes. All mammals possess a “master” circadian clock that resides in a specific area of the hypothalamic region of the brain. This area of the brain is responsible for regulating diverse physiological processes such as blood pressure, heart rate, wakefulness, hormone secretion, metabolism and body temperature. Each of these processes is in turn affected by time of day.

During daylight hours, the eye perceives light and light energy is transmitted via a network of nerve fibres to the brain. Here, the light signal activates a number of important genes and these “clock” genes are responsible for relaying signals conveying the time of day information to the rest of the body. Recent advances in the study of circadian rhythms and clock genes have shown that a molecular clock functions in almost all tissues and that the activities of possibly every cell in a given tissue are subject to the control of a clockwork mechanism. The role of the “master” clock in the brain is to communicate the light information to the clocks in the peripheral tissues, so that each tissue can use this information for its own purpose.

Thus, as day breaks and eyes perceive morning light, hormones are produced to help us to wake up, enzymes are activated in our digestive systems in anticipation of breakfast, heart rates increase, muscles prepare for exercise and many more circadian rhythms are initiated. This master clock in the brain, that controls so many bodily functions, must be reset on a daily basis by the photoperiod, whether it is sunrise and sunset or lights on and lights off, in order for an organism to be in harmony with its external environment. Jet lag occurs due to an abrupt change in the light-dark cycle and results from travel across multiple time zones, which in turn causes de-synchronization between an organism’s physiological processes and the environment.

Coupled to this is the fact that the circadian clock can only adapt to a new lighting schedule gradually and while the brain receives the light information directly, there is a further lag period involved in transmitting the time of day message to peripheral tissues. As a consequence, behavioural and physiological adaptation to changes in local time is delayed. This means that following a transmeridian journey, travellers are forced to rest at an incorrect phase of their circadian cycle, when they are physiologically entrained to be active and more importantly for the athlete, they are expected to perform when they are physiologically set to rest. As mammals, horses also suffer from the effects of jet lag.

Research is needed to understand the extent of physiological disruption caused by a transmeridian journey, the time period of the disruption and the overall effect it has on equine performance. Until now, no studies have been undertaken to investigate the physiological effects of jet lag in the horse. Studies in human athletes have demonstrated the detrimental effects of translocation on exercise capacity and performance. One early study examined human subjects following intercontinental flights consisting of eastward or westward journeys across multiple time zones (1). Results clearly demonstrated significant disturbances in heart rate, respiratory rate, body temperature, evaporative water loss and psychological function. Interestingly, these disturbances were found to be more profound following the eastward flight.

A more recent study conducted using top athletes from the German Olympic team investigated the effects of time-zone displacement on heart rate and blood pressure profiles (2). In athletes, blood pressure and oxygen supply to the organs are of utmost importance for optimal performance and successful competition. Rhythm disturbances in the 24-hour profiles of heart rate and blood pressure were found to be present up to day 11 after time-zone transition. The athletes were involved in intensive training programmes throughout the study and underwent frequent bouts of strenuous exercise.

Regular exercise at a set time in the 24-hour clock can strengthen circadian rhythms that are integral to physiological processes and can act as a timing cue secondary to light. It is also thought to aid in resynchronisation to a new time-zone. However, exercise was not found to improve the jet lag effects in this study, an observation that has relevance for the athletic horse in intensive training. The investigators concluded that following a flight across six time zones, athletes should arrive for their competition at least two weeks in advance in order to overcome the jet lag effects before competing.

Another study using fit human subjects examined performance times before and after an eastward journey across 6 time zones (3). Performance times for a 270m sprint were slower for the first 4 days following translocation as were times for a 2.8km run on the second and third days. This can be explained by the fact that the athletes’ internal body rhythms, including several neuromuscular, cardiovascular and metabolic variables and indices of aerobic capacity are out of synchrony with the environmental light-dark cycle following a transmeridian journey. Small mammals such as rats and mice have historically been used to study human circadian disorders such as jet lag. Current research being conducted at the Gluck Equine Research Center at the University of Kentucky has resulted in successful isolation of a number of ‘clock’ genes.

A comparison of these equine specific genes with their human counterparts has revealed an unusually high similarity between these two species at the DNA level, closer than the similarity observed between small mammals and humans. Unlike humans and horses, rats and mice are nocturnal animals and have yet to be proven as elite athletes. Further research is underway to investigate in detail the effects of jet lag on equine performance that will eventually lead to the development of measures to counteract these effects. Until then, information on the effects of transmeridian travel derived from studies on human performance can be used to provide guidelines to horse trainers, especially based on the similarity between the species in question. The severity of the jet lag effects can depend on a number of factors. These include the ability to preset the bodily rhythms prior to flying (4), the number of time zones crossed, the direction of the flight and individual variability.

Just as set exercise times can affect circadian rhythms in many physiological processes, feeding schedules also play an important role in entraining biological clocks, particularly within the digestive system. Horses anticipate feeding times. Banging of hooves on doors and rattling of empty feed buckets are common sounds that greet those responsible for feeding a yard of hungry horses. Therefore, it is important to change both feeding times and exercise schedules to mimic the new time zone prior to travel, in order to shorten the amount of time required for resynchronisation of digestive function and performance capacity upon arrival. Lighting is also of paramount importance. Exposing animals to early morning bright light for several days prior to an eastward journey across multiple time zones, or, extended hours of evening light prior to a westward journey, will help synchronize circadian rhythms to the new time zone prior to travel.

A recent study that tested a combination of approaches to hasten the resynchronisation of a group of elite sports competitors and their coaches to a westerly transmeridian flight, demonstrated the usefulness of combining melatonin treatment, an appropriate environmental light schedule and timely applied physical exercise to help the athletes overcome the consequences of jet lag (5). Melatonin, a hormone secreted by the pineal gland of the brain during the hours of darkness, is thought to help synchronize sleep-wake cycles and resynchronisation to a new time zone, but its suitability for these purposes has yet to be tested in the horse. Of course, these procedures to preset bodily rhythms need not be implemented if it is possible to arrive at the destination in sufficient time to allow natural re-entrainment to the new light-dark cycle.

For financial reasons, this is not necessarily feasible for the equine athlete. Two other important factors that determine the severity of jet lag effects are the number of time zones crossed and the direction of the flight. As one would expect, the greater the number of time zones traversed, the more severe the physiological disruption. For example, a flight from Europe to the East Coast of the United States, across six time-zones, would require a significantly greater resynchronisation time than a flight from the East Coast to the West Coast (three time zones), within the continental U.S. Any transmeridian journey in an eastward direction will result in a more profound disruption of circadian rhythms than a similar journey in a westward direction. The reason for this is a molecular one and involves the individual characteristics of certain clock genes. Suffice to say that clock genes react more rapidly to light than to darkness. When travelling in a westward direction i.e. from Europe to the United States, travellers enter an environment consisting of extended hours of evening light. The light continues to stimulate clock genes in the brain and adaptation to the new time zone occurs more rapidly. To some extent this may explain the success experienced by European horses at U.S. racetracks, even when they arrive three to four days prior to a race.

Knowing exactly how long it takes for the equine athlete to overcome any travel effects that may impinge on performance following such a flight, should provide valuable information to European trainers. In contrast, an eastward journey results in a shortened day length at the destination and requires a phase advance of the circadian clock. Travellers experience earlier nightfall and as the clock genes cannot respond well to darkness, an extended duration of jet lag. To emphasize, it will take an animal longer to adapt to the new light-dark cycle following an eastward flight and consequently longer to reach optimal performance levels following transit.

Pharmacokinetics deals with absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination of drugs and these steps are influenced by physiological function of the body, which we now know to be influenced in turn by time of day. The implications of this for the athletic horse following transmeridian travel is worth highlighting, as it underlines the importance of knowing approximate physiological resynchronisation time to a new time zone. For example, terbutaline, a bronchodilator similar to clenbuterol commonly used by equine practitioners, has a significantly longer half-life when administered in the morning than in the evening (6). This implies that drug clearance times can be affected by transmeridian travel. In addition to the disruption of circadian rhythms, travel stress can also be a significant factor in further compounding the effects of jet lag following the transportation of horses across multiple time-zones.

Major complications associated with long-distance travel include pleuropneumonia, otherwise known as ‘shipping fever’, dehydration and colic. Even in cool conditions, horses will often lose 2-5 pounds of body weight for every hour they travel, as they do not like to drink while travelling (7). Care of horses during long-distance transportation is an extensive topic that requires separate attention. At the Gluck Equine Research Center, preparations are underway to conduct several experiments that will simulate phase advances and delays in the lighting schedule of groups of horses, thus mimicking eastward and westward journeys, so that the molecular and physiological effects of jet lag and the time duration of these effects can be investigated. The goal of this research is ultimately to provide practical guidelines to trainers in order that measures can be taken to counteract the detrimental effects of jet lag on performance, therefore leveling the playing field for horses competing away from home.