What is equine welfare? Asks Johnston Racing’s vet Neil Mechie

Neil Meche

The world of equine welfare—and animal welfare in general—is a proverbial can of worms. Decisions regarding equine welfare must be made on logical scientific evidence and not be biased by emotion or fear of incorrect perceptions in the media or public eye. As with many things in life, education is the key, especially in a world where large parts of the population have very little experience or knowledge of keeping or working with animals.

The welfare of animals is protected in national legislation in the UK. The Animal Welfare Act 2006 makes owners and keepers responsible for ensuring that the welfare needs of their animals are met. These include the need:

for a suitable environment (place to live)

for a suitable diet (food and water)

to exhibit normal behaviour patterns

to be housed with, or apart from, other animals (if applicable)

to be protected from pain, injury, suffering and disease

Reading these concise bullet points, one would think it quite simple to meet these needs, but issues arise when it comes to interpreting and putting this guidance into practice.

As an insight into how emotive language can change the interpretation of animal welfare requirements, below are the The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) “Five Freedoms,” which are not too dissimilar to the above but portrayed in a different light:

Freedom from hunger and thirst

Freedom from discomfort

Freedom from pain, injury or disease

Freedom to express normal behaviour

Freedom from fear and distress

The RSPCA is a charity champions animal welfare, and the use of words such as hunger, thirst, discomfort, fear and distress conjure up images of tortured animals wasting away in squalor. There is no need for this dramatic language when the preservation of welfare only actually requires common sense and compassion.

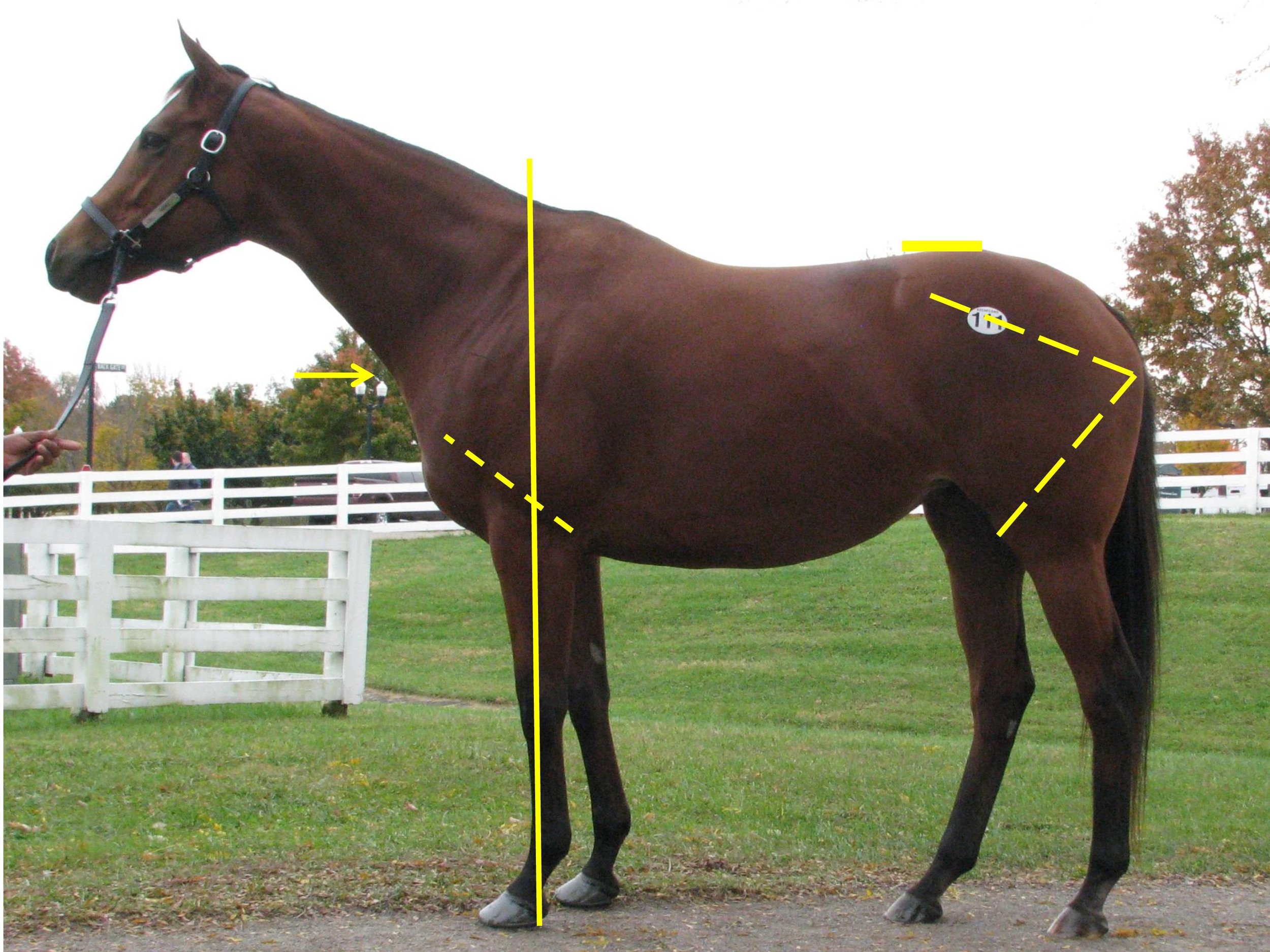

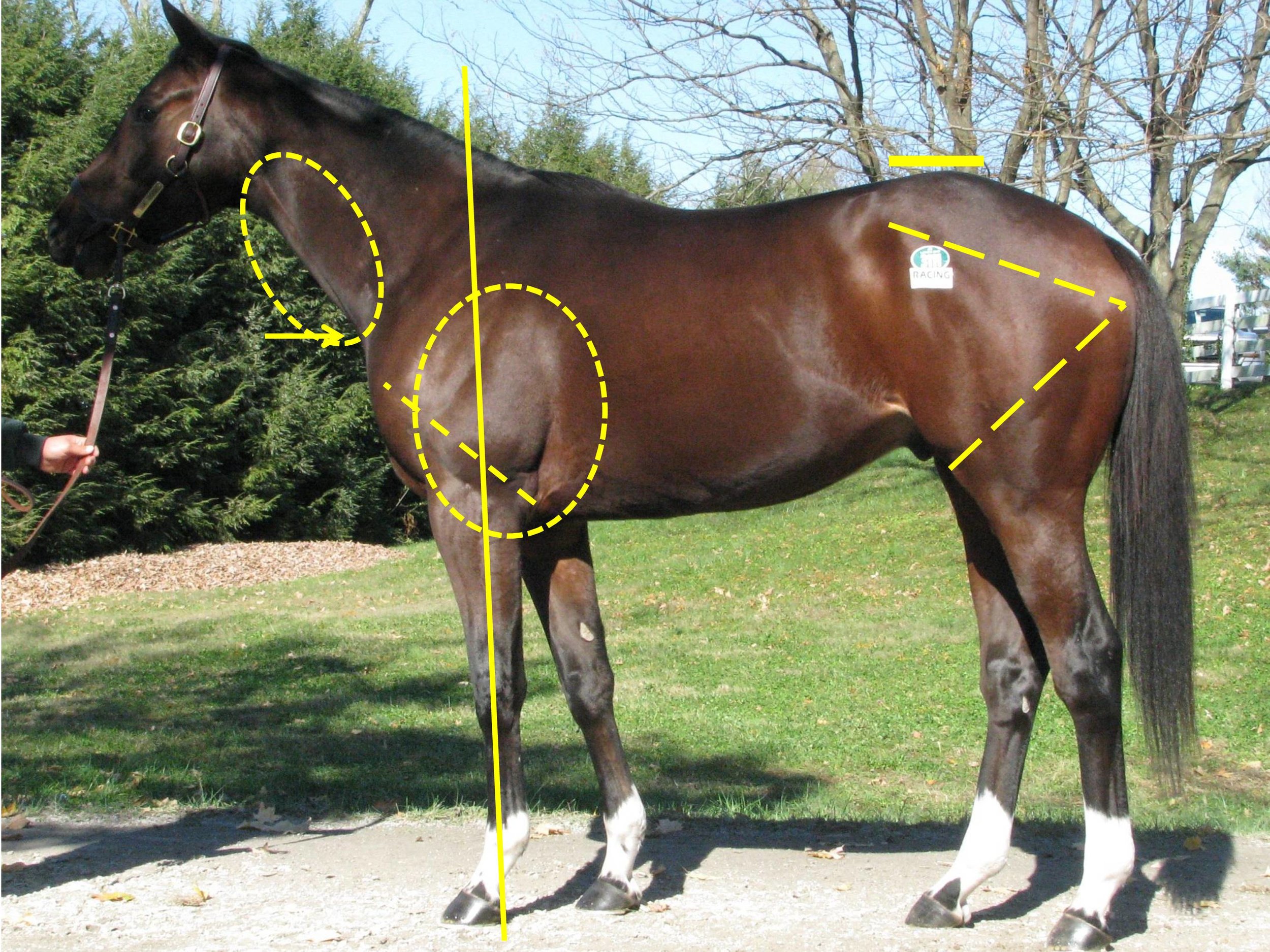

The same can be said when considering the welfare of horses, but sadly this is not the case. The biggest welfare issues facing the horse population are not, as the media would have you think, horses breaking their legs on racetracks or the travelling community mistreating horses at Appleby Fair. It is obesity and the mis-management of horses in the general population. Every day horses are being killed by a plethora of issues caused by over-feeding and poor management regimes. Laminitis, colic and numerous hormonal and metabolic diseases negatively affect the welfare of thousands of horses each year and are in a large part caused by the poor knowledge and horsemanship of their owners. It is now a large part of most equine vets’ job to educate horse owners on appropriate feeds and management regimes for their horses.

Racehorses, on the contrary, are looked after with the highest of standards as they are athletes competing at a high level.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Are we going soft on our horses?

By Amy Barstow

Over the years there has been a steady move away from traditional concrete surfaces in yards towards surfaces that are generally considered softer, such as rubber. Furthermore, in some areas, the surfaces of the tracks which link yards with training facilities (horse walks) have also moved towards ‘softer’ surfaces. This has led some to wonder if our horses are missing out on a key opportunity to condition their musculoskeletal system. This article will explore what the scientific research tells us about how different surfaces affect the horse and what this might mean for musculoskeletal conditioning and injury resistance.

The majority of the research that has highlighted the links between surfaces and injuries is from epidemiology studies. These studies view large populations of horses and pull together lots of different factors to elucidate risk factors for injury. They, therefore, do not attempt to investigate why surfaces may be implicated as a risk. To understand the link between surface and injury risk, other types of research must be done including biomechanics studies, lab-based studies on bone and tendon samples and prospective experimental studies. Biomechanics studies explore how the horse, especially their limbs and feet, move on different surfaces and the forces and vibrations that they experience. Lab-based work investigates how musculoskeletal tissues respond to loading and vibrations at the cellular and extracellular level. Prospective experimental studies take a group of horses and expose them to different environments (e.g., conditioning on different surfaces). Then you compare the groups, for example, looking for signs of musculoskeletal injury using diagnostic imaging techniques. The research done using these different techniques can then be pieced together to help us decide how to better manage the health and performance of racehorses.

There is a wealth of epidemiological data to suggest that the surface type and condition during racing influences the occurrence of musculoskeletal injuries in the racehorse. Though it must be remembered that musculoskeletal injury is multifactorial with training regimens, race distance, the number of runners, horse age and sex all coming into play. Though there are comparably fewer data available relating to the effect of training surface type and properties on musculoskeletal injury rates, what is available also suggests that firmer surfaces increase the risk of sustaining an injury either during training or racing. For example, horses trained on a softer, wood fibre surface are less likely to suffer from dorsal metacarpal disease (bucked shins) than those trained on dirt tracks. However, horses trained on a traditional sand surface have been shown to be at a greater risk of injury (fracture) during racing. This could be due to the soft sand surface not stimulating sufficient skeletal loading to adequately condition the musculoskeletal system for the forces and loading experienced during racing. It could also be the result of horses racing on a surface with very different properties to those that they trained on.

So far the majority of the scientific research discussed relates to horses galloping and cantering, which are not the gaits that they will generally be using around the yard or getting to and from the gallops. There is very little work to link sub-maximal (low) speed exercise on different surfaces to injury in horses. In a small group of Harness (trotting) horses, those trained on a softer surface had a lower incidence of musculoskeletal pathology identified using diagnostic imaging techniques, compared to those trained on a firm surface. There is also evidence of the benefit of softer surfaces in livestock housing. Experimental work by Eric Radin in the 1980s found that sheep kept on a concrete floor compared to a softer dirt floor had more significant orthopaedic pathologies at postmortem. Furthermore, the use of rubber matting reduces the incidence of foot lameness in dairy cattle. So it would appear that a softer ground surface is beneficial even at sub-maximal intensity locomotion.

The epidemiological data discussed so far tells us that surface can play a role in injury, but it does not provide any answers for why that may be the case. From a veterinary and a scientific perspective, I am interested in how different surfaces influence limb vibration characteristics and loading in horses. …

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Diversity and inclusion in European racing

By Dr Paull Khan

When France decided in 2016 to introduce a weight allowance for female riders, it set the racing world murmuring and shone a light on the issue of gender diversity among jockeys.

Jean-Pierre Columbu, vice-president of France Galop, explains: “My president, Edouard de Rothschild, who had introduced Lady Riders’ races about a decade earlier, still felt they were something of a ‘ghetto’, and wanted to do more to see females compete on equal terms”. The 2-kg (4.4lbs) allowance applied to both flat and jump races, but excluded Pattern races. Last year, the allowance was reduced on the flat to 1.5kg.

It was a bold step and one that has quickly produced some dramatic results. Within three years, female professional flat jockeys are getting three times the number of rides they used to, and their winners tally has risen by a staggering 340%. Despite the exclusion of the most lucrative races, the prize money won by horses ridden by females has also nearly trebled, from €4.1M to €12M. To Columbu, this increase in earnings among lady riders is crucial to the recruitment and retention of women. “In our Jockey School”, he notes, “65% are now female. And there are, of course, many, many females in our stables who must have the opportunity to earn money”.

Indeed, it could be said that that the allowance has achieved its objective. Female riders’ percentage of rides, which are winners, has improved from 7.14% to 9.08%—rapidly closing in on the male riders’ equivalent figure of 9.73%. So has the experiment run its course, and will the allowance soon be phased out? Columbu does not think so.

“The allowance is going to stay”, he concludes. “I used to be a surgeon. In males, 35% of body weight is made up of muscle. In women, that figure is 27%. That is why the allowance is needed”.

Of course, France is far from being alone in experiencing under-representation of women riders.

Other countries have been studying the French experiment with interest from afar. In Britain, flag-bearer Hayley Turner’s exploits are well-known. However, not all in the garden is rosy. Rose Grissell, recently appointed Head of Diversity and Inclusion for British Racing, notes: “Recent successes should be celebrated and promoted, but there is further to go. Fourteen percent of professional jockeys are female, but women receive just 8.2% of the rides and, in 2018, no woman rode in a flat Gp1 race. So, while the trends are in many ways encouraging, they do not apply across the board”.

These concerns are echoed by the organisation Women in Racing. Established in 2009, Women in Racing was formed to encourage senior appointments at Board level across the industry and to attract more women into the sport. That ambition remains, but today, according to its chair, Tallulah Lewis, there is more focus on strengthening career development for women at all levels. For Lewis, a prime concern is the attrition rate; in other words, the fact that the 14% figure for female riders that we have noted above occurs despite the ratio of new recruits entering into racing through the two racing schools in Britain, being as high as 70:30 in favour of females. Understanding their lack of progression is a key aim.

Grissell, indeed, intends to examine issues of recruitment, training and retention, looking to help either remove the barriers to lady riders’ success or to lend support. One tactic might be to challenge the perception of the innate inferiority of the female jockey. Grissell again: “A study by PhD student Vanessa Cashmore identified that punters undervalue women riders: a woman riding a horse at odds of 9/1 had the same chance of victory as a man riding one at 8/1”.

Such findings call into question the need for a gender-based riders’ allowance and, indeed, British lady riders themselves have voiced opposition to the concept.

The French experiment—and its undoubted success—presents a dilemma to those who seek better outcomes for women riders but who are convinced that they are equally effective as their male counterparts, given the opportunities.

“We applaud what the French have done in this experiment, as it gives us all more information than we had before”, says Lewis. “Our concern is that it is based on the premise that women are not men’s equal when it comes to race riding—something the evidence disproves”.

Belgium, which boasts the highest percentage of the countries polled, has crunched the numbers and decided against following the French example. Marcel de Bruyne, director of the Belgian Gallop Federation, explains:

“We have the same percentage of females—43% among our professional and amateur riders and, as they achieve approximately the same percentage of winning rides as the men, we do not envisage giving a weight allowance for females”.

(All of which suggests Belgium would make an interesting case study.)

Spain, by contrast, is due to have introduced a 1.5-kg allowance for females by the time this magazine is published. It would be surprising if other countries did not decide to follow suit, either by replicating the weight allowance or conjuring some other incentive for the female jockey. A prize money premium for connections who engage female riders would be one such option, which would have the benefit of leaving the actual terms of competition undistorted.

Of course, gender diversity is but one aspect of diversity in general. It is often the first to be tackled because of the (at least traditional) binary classification applying to the sexes, and the relative ease of data collection. But diversity and inclusion in ethnic or racial terms, in sexual orientation and identification, in physical ability, etc. are all key components when assessing the extent to which a sub-group reflects the wider society in which it sits.

The argument is now widely accepted that homogeneity stifles innovation and that, in addition to any altruistic motivation for advancing the cause of the under-represented, there is also an economic, self-interested imperative for organisations to do so. And there is every reason to suppose that this applies equally to racing. The benefits, in terms of staff recruitment and retention, for example, that would likely flow from well-managed diversity should be just as applicable to, say, a trainer’s yard as to any other commercial operation.

Talking of trainers, the table below shows the percentage of female professional licensed trainers by country, and as with the professional jockeys, again reveals a very wide variation.

What, if anything, is being done to address this disparity? Or indeed, manifestations of a lack of diversity among other groups within racing: administrators and racecourse executives, for example, or, looking more broadly, among those who attend races, or place bets on horseracing?

The short answer would appear to be: not a lot. The country which has done by far the most work in this space would appear to be Great Britain where, two years ago, the British Horseracing Authority established a Diversity in Racing Steering Group.

The story starts in 2017, when Women in Racing jointly commissioned and published a study by Oxford Brookes University, entitled ‘Women’s representation and diversity in the horseracing industry’. The report found evidence of ‘a lack of career development opportunities (at all levels including jockeys), progression and support, some examples of discriminative, prejudice and bullying behaviour, barriers and lack of representation at senior and board level, and negative experiences of work-life balance and pastoral care’.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Down Royal racecourse, tradition reborn

By Lissa Oliver

Down Royal racecourse in Northern Ireland boasts a heritage as regal as its name. They have been racing on the course since the early 18th century—the land originally donated by the first Marquess of Downshire, but its history goes back even further. In 1685, King James II issued a Royal Charter and formed the Down Royal Corporation of Horse Breeders. In 1750, King George II donated £100 to run the King’s Plate, a race still run today as one of the summer’s highlights, the 2800m Listed Her Majesty’s Plate. The Ulster Derby, now a premier handicap, is the most valuable Flat race hosted by the track, but Down Royal is best loved for the National Hunt Festival held at the start of November and headlined by the Champion Chase.

Inevitably, a rich history must also include challenges and threats and the racecourse has been no exception. As recently as last year the course faced the prospect of closure, its operators, Down Royal Corporation of Horse Breeders, signalling intent to cease operations in October. Fortunately, owners Merrion Property Group took over the running of the course from January of this year and it has been business as usual.

Emma Meehan CEO

With a bright new future and lofty ambitions, Manager Emma Meehan is charged with seeing those aims achieved, but the path ahead remains fraught with new challenges, not least the spectre of Brexit. Based in the UK, but under the authority of the Irish Horseracing Regulatory Board (IHRB), places Down Royal in a tricky position and the timing of the NH Festival opening on 1 November could bring unknown difficulties.

“The impact of any change in the current Tripartite Agreement could create initial difficulties”, Meehan recognises. “We remain in limbo regarding Brexit and continue to communicate with DAERA and the IHRB. We are ready to react to support the passage of runners and riders to our flagship festival on Friday 1 November and Saturday 2 November and beyond. The landscape is changing daily at British Parliamentary level; a general election could be on the cards very soon. Whatever the outcome, we will adapt to any new requirements and ensure we provide maximum assistance to our owners and trainers”.

Facing the unknown isn’t new territory to Meehan and she joined Down Royal at a particularly difficult time, following a successful 14 years as marketing manager at Dundalk Racing Stadium. “I found the transition in the early stages tumultuous to say the least”, she admits. “I likened it to trying to put a jigsaw puzzle back together again and I had to figure out where pieces were and, indeed, that some individuals were holding some of those pieces behind their backs. It was a challenging phase, but one that I grew from personally.

“Fast-forward to now; nine months on and I have a wonderful team and I couldn’t be happier.

The support I have received from Merrion Property Group and their progressive mind-frame has complimented my thinking at all levels. Merrion Property Group have a vision for Down Royal, with racing centric to that vision. We have a five-year investment strategy in the pipeline to bring the facilities, both for the social racegoers and racing fraternity, in line with a Grade 1 track, and modernising in tandem. I’m very excited about the changes afoot at Down Royal”.

In the modern landscape, investing in a racecourse doesn’t seem the best of ventures, particularly a ‘fixer-upper’ in property agent parlance, but Merrion Property Group bought the racecourse as far back as 2006 and saw the end of the lease with the Down Royal Corporation of Horse Breeders as an opportunity to run its own racing-centred business from the track.

“The overall site and infrastructure at Down Royal are huge. Continuous investment is fundamental to remaining competitive in the industry and providing a best in class environment for owners, trainers, bookmakers, punters and all the services and supports which go into racing”, Meehan explains.

“Our aim is to provide memorable and sociable experiences for groups, businesses and sports people, looking to bring together racing, good food and entertainment. Our investment compliments this objective”.

She sees the importance and influence of a community vital and central to the objectives of the new management. “It’s hugely important that the racecourse is the epicentre of the local community, and it’s our intention to embrace the community through several initiatives. Looking ahead to 2020, we are choosing local charities to collect at our gates, ensuring that the platform and the opportunity to raise monies is directed back to our charitable community partners. …

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Planning a diagnostic-led worm control programme

Common horse worms

By Dr Corrine Austin (Austin Davis Biologics) and Prof Jacqui Matthews (Roslin Technologies)

Planning a diagnostic-led worm control programme

All horses are exposed to worms while grazing, but how we control these parasites is essential to horse health and performance. Most horse owners are aware of testing to determine whether their horse needs deworming. The tests comprise faecal worm egg counts (FEC) for redworm/roundworm detection and saliva testing to detect tapeworm infections (standard FEC methods are unreliable for tapeworm). Until now, encysted small redworm larvae have remained undetectable as FEC only determines the presence of egg laying adult worms. This has meant that routine winter moxidectin treatment has become recommended practice to target potentially life-threatening burdens of small redworm encysted larvae. Excitingly, a new small redworm blood test is being commercialised* which detects all stages of the small redworm life cycle, including the all-important encysted larval phase. Together, these tests offer a complete worm control programme for common horse worms using diagnostic information. This is known as ‘diagnostic-led worm control’ (see Figure 1 for common worms in horses). Essentially, testing is used to tell you whether your horse needs deworming or not.

Why should you use testing to determine whether you should use dewormers or not?

Gone are the days of routinely administering dewormers to every horse and hoping for the best. That strategy is outdated as it has caused widespread drug resistance in worms (i.e., worms are able to survive the killing effects of dewormers and remain in place after treatment, which can lead to disease and in worst cases, death). To reduce the risk of further resistance occurring, we need to ensure that dewormers are only used when they are genuinely needed—when testing detects that horses have a worm burden requiring treatment. Regular testing also helps identify horses likely to be more susceptible to infection and thus at risk of disease in the future.

How to plan your horse’s worm control programme ….

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Trainer Profile: Cathrine Erichsen

By Amie Karlsson

With 400 winners and plenty of pattern-race successes to her name, Cathrine Erichsen is the most successful female trainer ever in Norway.

This interview takes us to Oslo, or to be more precise, a 12-km drive northwest of the city center. Here, tucked away in a quiet residential area, we find Øvrevoll Galoppbane, the sole thoroughbred venue in Norway.

It is the end of August. Erichsen, an independent, charismatic woman with more than 400 winners under her belt, has just got back to routine again after the Norwegian Derby Weekend—the highlight of the Norwegian racing calendar a few days earlier.

Øvrevoll is where Erichsen participated in her first amateur race, saddled her first winner and enjoyed her first black type success. Today, it is where she cares for a string of almost 25 thoroughbreds. Erichsen is one of ten professional trainers at Øvrevoll—there are twenty in total in the country—and she has her base in one of the barns on the backstretch.

She has been training for half her life, but the last four years have been particularly fruitful. In the last three weeks of August, she had won two Gp3 races in Scandinavia with two different horses.

In the middle of summer, Øvrevoll is a beautiful place. Barns, outdoor boxes, lunge pits, paddocks and horse walkers are scattered around the backstretch and in the infield. It is charming and a little bit unpolished racing venue surrounded by mature trees, which provide green barriers between the racecourse and the adjacent villas.

Right now, November seems an eternity away, when freezing temperatures and just a few hours of daylight brings the racing season to a halt until the following April.

One would forgive a Norwegian racehorse trainer for complaining about the winters—even trainers living at latitudes far south of Norway tend to mutter and moan about the weather and training conditions of the winter months.

However, Erichsen’s view on training racehorses in Norway in the winter may come as a surprise.

She explains: “In my opinion, our strong winters is one of the particulars with training horses in Norway, but it is definitely one of the benefits. The cold gets rid of a lot of bacteria, and the snow is one of the best surfaces you can train horses on.”

“We use special shoes with studs which prevent the horses from slipping and snow rim pads that prevent snow packing into their feet. The track workers at Øvrevoll are great. They harrow the snow and make it into a nice training surface. It is smooth—and cold. What other surfaces are there that cool the horses’ legs whilst they train?”

Erichsen talks from experience. More than 35 winters have passed since she, for the first time, sat on a racehorse at the age of 12.

For a child growing up in Norway, horse racing may not be the first thing that springs to mind when given the opportunity to choose a hobby. But the young Cathrine liked horses, and a school friend happened to be the daughter of a racehorse trainer; and that is how Erichsen got acquainted with the racing industry.

It did not take long until her passion for horse racing was developed. When she turned 15 (the minimum age for race riding in Norway), she began a successful stint as an amateur rider.

“I was lucky to get the chance to ride in the Fegentri World Champion series for amateur riders. The race riding experience is a great benefit for me as a trainer, and I learnt a lot from riding in different countries.”

Despite the successful years as an amateur rider, Erichsen did not consider turning her hobby into a career. She had other plans in life and signed up for a degree in economics and marketing. For a while, her only connection to the racing industry was her riding horse, a retired racehorse.

“One day I needed to get hold of the farrier. I knew he would be shoeing in a stable at Øvrevoll that day, so I rang the trainer.”

The trainer answered, but before the phone was passed over to the farrier, Erichsen had found herself with a job.

“He asked if I wanted to come and ride out, and I thought ‘why not?’ I was studying and needed some money.”

What the economics student did not expect was that she, a year later, would have the sole responsibility for the stable.

“One day, after I had ridden out part-time for a year, the trainer told me that he had decided to retire from training. He offered me to take over his yard. At the time I was 25 years old and quite fed up with school, so I thought it could be a fun thing to do for a while.”

Erichsen with Gro Kittilsen and the mare Seaside Song (GB)

Being a trainer seemed quite easy, at least to start with. A stable full of race-fit horses, well-established routines, several loyal owners and an experienced employee who knew the stable inside out. Erichsen was off to a head start in the game of racehorse training.

“It was great. I didn’t have much experience, of course, but I got everything served: here is a barn, here are 14 horses, here is the girl who works for you. What I didn’t think about was that I soon would have to acquire new horses, recruit more owners and find new employees!”

Erichsen laughs when she recalls the beginning of her new career.

“When the employee some time later handed in her notice, it was certainly a cold shower for me. That wasn’t according to plan!”

There were times when the young Norwegian wished she had stayed far away from the racehorse business. …

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Brexit remains the heaviest cloud on the horizon

By Lissa Oliver

This is now the third update on Brexit we have carried and we could easily reprint the first, from March 2018; so little has changed or moved forward. Alarmingly, the bleak 2018 predictions from those involved at the highest level have come to bear, yet Britain and the EU have appeared to turn a blind eye to the prospect of a no-deal Brexit until the last possible moment. While we look at the current views and contingency plans of individual countries most affected, it is clear that their problems are shared by all, and a common thread runs throughout.

EEA nationals and UK nationals

We all need to be aware of how Brexit will affect our freedom of movement and right to live and work throughout Europe and the UK. Any EEA national with five years continuous residence in the UK can apply for Permanent Residence to protect them from future legislative changes. Applicants must have been resident and in employment, or self-employment, for five years; and it is recommended to apply before the official date of Brexit.

There are strong indications that the current Common Travel Area of the UK and Ireland is likely to remain, to enable Irish nationals to move freely and work in the UK, but this remains unconfirmed; and it is recommended that Irish nationals living and working in the UK apply for Permanent Residence.

The EU has yet to decide how UK nationals living and working in the EEA will be treated. They may qualify for Permanent Residence in the applicable country and are advised to make an application prior to the UK’s withdrawal from Europe.

France

Edouard Philippe

The economy of the French equine sector is driven by horseracing, sports and leisure, work, and horse meat production. While the sports and recreation sector is responsible for the majority of horses (68%), horseracing has the largest economic impact and financial flow (90%), for only 18% of the horse population, and will be the most affected by Brexit.

The start of the year found France preparing for a disaster scenario, and the view hasn’t softened. Prime Minister Édouard Philippe has told press,

“The hypothesis of a Brexit without agreement is less and less improbable. Our responsibility is to ensure that our country is ready and to protect the interests of our fellow citizens.”

In January he initiated a no-deal Brexit plan prepared in April 2018. Philippe’s priority is to protect French expatriate employees and the British living in France in anticipation of the restoration of border control.

Fishing is considered the business sector most at risk, but Philippe has also looked to protect the thoroughbred industry with a €50m investment in ports and airports, where 700 customs officers, veterinary controllers and other state agents have been added—in the hope of avoiding administrative delays. He told press,

“It will be necessary that there are again controls in Calais.”

Dr Paul-Marie Gadot, France Galop, is also working to avoid delays at the border posts. "The political negotiation is still going on, as you know, and as long as it lasts we will not get agreement on the movement of horses. We have prepared for two years, with our Irish and English counterparts, a technical solution—the High Health Horse status—which would allow thoroughbreds and the horses of the Fédération Equestre Internationale to benefit from a lighter control.

“This organisational scheme was presented to the Irish, UK and French Ministries of Agriculture, and we received their support. It was also introduced to the International Office of Epizootics, which is WHO for animals, and it was very favourably received. We have presented it to the European Commission, but we are not getting a favourable answer at this time.

“In the absence of agreement, border control will be put in place. This means for the public authorities and the European Commission the implementation of ‘Border Inspection Posts’ with the ability to process movements. Our departments are very aware that this situation will be very difficult to manage without endangering the economic activity and the well-being of horses. We are working on palliative solutions, but I strongly fear that the situation is unmanageable.”

Gadot points out there are 25,000 horse movements per year between Ireland, the UK and France, and any hindering of these movements would be a blow to international racing and participation and to the breeding industry. Any challenge to the current freedom of movement could also threaten sales companies such as Arqana, where Irish and British-bred horses are catalogued, and Irish and British buyers are active.

Germany

The Haile Institute for Economic Research reveals that a hard Brexit will hit employment in Germany the hardest, with an estimated loss of 102,900 jobs; although that is just 0.24% of the country’s total employment figure. With its thoroughbred industry barely figuring in any economic impact, it is little wonder that Germany’s sport-related concerns focus on football. But the issues facing Britain’s Premiership are similar to racing’s problems and also heavily tied to Ireland.

Currently, as per EU law, Britain’s Premier League clubs are allowed to have as many EU players in a team as they wish, but a minimum of eight players in a 25-player team must be British. Elsewhere, Portugal limits non-EU players to just three per top flight team, with none allowed in the lower leagues. Italy also has restrictive rules on the purchase of non-EU players. If German football managers are concerned by the effect Brexit will have on the transfer market, how worried should British trainers be at the prospect of similarly curtailed recruitment?

And the concerns of German trainers? These are not being highlighted by the general press or by the government, but German racing and breeding are fairly self-contained and self-sufficient. How many British and Irish-bred horses are catalogued at the BBAG, however, and what percentage sell to Britain and Ireland? Ireland may still be in the EU, but its landbridge will not be come October.

At the 2019 BBAG Yearling Sale, five British-bred yearlings were catalogued and 18 Irish-bred—four of which were offered by an Irish agent. The top five lots at the 2018 sale were purchased by Godolphin, Peter and Ross Doyle Bloodstock and Meridian Bloodstock; and the sixth highest-priced yearling was foaled in the UK, as was the ninth in the listings. Fetching €110,000 and €100,000 further down the list were two Irish-foaled colts, both bought by German agents. The marketplace is cosmopolitan, and no market can afford to lose two supplier links or two buyer links.

Sweden

Swedish trade minister Ann Linde warns that a no-deal Brexit could have major implications for the country, which has a prosperous trading relationship with Britain. “The big companies have the possibility to analyse what is happening and prepare themselves, but there are too many small and medium-sized companies which have not fully prepared,” she points out. The Swedish National Board of Trade has sent out checklists to companies to work through to understand the consequences of a no-deal Brexit.

Linde is also concerned for the futures of 100,000 Swedes living in Britain and 30,000 Britons living in Sweden. Hans Dahlgren, the Secretary of State for Exiting the EU, fears it is unclear how the new British government will treat EU citizens who want to move to the UK for work after 31 October.

"The previous British government had made some openings for people coming to the UK after Brexit, and those statements have not yet been endorsed by the new government," he said.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

The Balancing Act

By Catherine Rudenko

Key considerations when reviewing what you feed and if you should supplement

With so many feeds and supplements on the market, the feed room can soon take on the appearance of an alchemist’s cupboard. Feeding is of course an artform but one that should be based on sound science. In order to make an informed decision, there are some key questions to ask yourself and your supplier when choosing what ingredients will form your secret to success.

Question #1: What is it?

Get an overview of the products’ intended use and what category of horse they are most suited for. Not every horse in the yard will require supplementing. Whilst one could argue all horses would benefit from any supplement at some level, the real question is do they need it? Where there is a concern or clinical issue, a specific supplement is more likely warranted and is more likely to have an impact. A blanket approach for supplements is really only appropriate where the horses all have the same need (e.g., use of electrolytes).

Question #2: Is it effective?

There are many good reasons to use supplements with an ever-increasing body of research building as to how certain foods, plants or substances can influence both health and performance. Does the feed or supplement you are considering have any evidence in the form of scientific or clinical studies? Whilst the finished product may not—in a branded sense—be researched, the active components or ingredients should be. Ideally, we look for equine-specific research, but often other species are referenced, including humans; and this gives confidence that there is a sound line of thinking behind the use of such ingredients.

Having established if there is evidence, the next important question is, does the feed or supplement deliver that ingredient at an effective level? For example, if research shows 10g of glucosamine to be effective in terms of absorption and reaching the joint, does your supplement or feed—when fed at the recommended rate—deliver that amount?

There is of course the cocktail effect to consider, whereby mixing of multiple ingredients to target a problem can reduce the amount of each individual ingredient needed. This is where the product itself is ideally then tested to confirm that the cocktail is indeed effective.

Question #3: How does it fit with my current feeding and supplement program?

All too often a feed or supplement is considered in isolation which can lead to over-supplementing through duplication. Feeds and supplements can contain common materials, (i.e., on occasion there is no need to further supplement or that you can reduce the dose rate of a supplement).

Before taking on any supplement, in addition to your current program, you first need to have a good understanding of what is currently being consumed on a per day basis. …

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Bleeders - the facts, fiction and future direction

By Dr. David Marlin

We are now approaching half a century since Bob Cook pioneered the use of the flexible fibreoptic endoscope, which allowed examination of the respiratory tract in the conscious horse. One of the important outcomes of this technique was that it opened the door to the study of ‘bleeding’ or exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage (EIPH). But nearly 50 years on the irony is perhaps that whilst we have become good at describing the prevalence of EIPH and some of the factors that appear to increase the severity of EIPH within individual horses, we still lack a clear understanding of the condition and how to manage it. I use the term manage rather than treat or prevent as our knowledge of EIPH must show us that EIPH cannot be stopped entirely; it is a consequence of intense exercise. The other irony is that in the past 50 years, by far the majority of research into the management of EIPH has focussed on the use of the diuretic furosemide. Whilst we have good evidence from controlled studies that furosemide reduces the severity of EIPH on a single occasion, we still lack good evidence to suggest that furosemide is effective when used repeatedly during training and or racing; and there is also evidence to the contrary.

Let’s review some basic facts about EIPH, which should not be contentious.

EIPH is the appearance of blood in the airways associated with exercise.

EIPH occurs as a result of moderate to intense exercise. In fact, EIPH has been found after trotting when deep lung wash (bronchoalveolar lavage or BAL) is done after exercise.

EIPH most often involves the smallest blood vessels (capillaries) but can sometimes and less commonly be due to the rupture of larger blood vessels.

The smallest blood vessels are extremely thin. Around 1/100th the thickness of a human hair. But this extremely thin membrane is also what allows racehorses such as thoroughbreds, standardbreds and Arabs to use oxygen at such a high rate and is a major reason for their athleticism.

EIPH is a progressive condition. The chance of seeing blood in the trachea after exercise increases with time in racing.

EIPH is variable over time, even when horses are scoped after the same type of work.

If you ‘scope a horse after three gallops in a row, you can expect to see blood in the trachea on at least one occasion.

EIPH damage to the lungs starts at the back and top, and over time moves forward and down and is approximately symmetrical.

Following EIPH the lung becomes fibrotic (as scar tissue), stiffer and does not work as well. The iron from the blood is combined with protein and stored permanently in the lung tissue where it can cause inflammation.

High blood pressure within the lung is a contributing factor in EIPH. Horses with higher blood pressure appear to suffer worse EIPH.

There is also evidence that upper airway resistance and breathing pattern can play a role in EIPH.

Airway inflammation and poor air quality may increase the severity of EIPH within individual horses.

Increasing severity of EIPH appears to have an increasing negative effect on performance.

Visible bleeding (epistaxis) has a very clear and marked negative effect on performance.

In order to make progress in the management of EIPH (i.e., to minimise the severity of EIPH in each individual), there are certain steps that trainers can take based on the information we have to date.

These include:

Ensuring good air quality in stables

Regular respiratory examination and treatment of airway inflammation

Reduced intensity of training during periods of treatment for moderate to severe airway inflammation

Extended periods of rest and light work with a slower return to work for horses following viral infection

Addressing anything that increases upper airway resistance (e.g., roaring, gurgling)

Avoiding intense work in cold weather

Avoiding extremes of going

Limiting number of training days in race preparation and increasing interval between races

Endoscopy

FUTURE OPPORTUNITIES IN UNDERSTANDING AND MANAGING EIPH

We have to accept EIPH as a normal consequence of intense exercise in horses. Our aim should be to reduce the severity to a minimum in each individual horse. However, there are areas in which we still need a much greater scientific understanding.

What actually causes the capillaries to leak or rupture?…

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Racing Groom – the .com needed by every country

By Lissa Oliver

You would think that racehorses bring more than their fair share of issues to a stable, but more often than not they are the simplest aspect of the job of training. They don’t look after themselves, however, and that’s where it gets complicated. Shortage of staff and the difficulties of staff retention are subjects we have dealt with in almost every issue, and the problem isn’t going away.

Part of the problem could be the image the racing industry presents of itself and the perceived lack of career progression; even trainers are sometimes unaware of the many and varied skill sets within their staff. Fortunately for the UK, this problem is now being addressed and hopefully rectified over the coming years, with the aid of an innovative new website originated, created and funded jointly by the National Trainers Federation (NTF) and the Racing Foundation.

Shelley Perham is the Nationals Trainers Federation (NTF) consultant for Recruitment and Retention of Racing Staff.

In the UK, Shelley Perham is the National Trainers Federation’s (NTF) consultant for Recruitment and Retention of Racing Staff and explains the reasoning behind racinggroom.com. “Racing Groom started as a mind map to pull together all the fragmented pieces of information from various stakeholders who offer services of support to racing grooms.

“When I googled ‘how to become a soldier’, there was an in-depth amount of content to help at the moment of decision making. I googled ‘how to become a racing groom’, and it only led to the job boards and training providers. From the trained eye, there was no proper job description or anything to inspire a young person to look further at a career as a racing groom”.

Things have moved on significantly now, however, and the current career advice given is impressive, Perham points out. “There is a huge package of support and benefits which accompanies the job and I wanted to pull it all together in one place so we could demonstrate that there was no better time to work in racing”.

Perham’s background is showing and competing, and she recognised the benefits and support offered by racing are vastly different to that which grooms are offered in other equine disciplines, “but at that time we weren’t shouting from the rooftops about it”.

The racinggroom.com hub came about after Perham looked at her daughters’ university portal, where students can log in to find out what is happening on campus, access discounts and read content relevant to their studies. “We don’t have a staff intranet, and the NTF sends out important notices to trainers which may not always pass down the line to staff. I wanted to help staff feel empowered, recognised and valued, so providing industry news direct to them seemed to be a logical step”.

When Perham started the role of consultant to the NTF, her first question was ‘what had happened to all the racing grooms who had left the industry’? There was no database which could be used to contact former grooms to inform them that things had changed since they had left, or to run a survey to ask why they left. It seemed logical to her for the NTF to start its own database where we could communicate with staff.

“We are dealing with over 4,000 racing grooms, which is a decent number to ask suppliers and businesses to make offers of discounts on products that racing grooms use on a day-to-day basis. The ambition is to have all racing grooms in the UK registered as members, then we can start approaching companies to offer staff discounts and rewards”.

It was a very ambitious idea, to say the least, and finding a website agency able to deliver was the first step, but once sourced, the project happened quite quickly in just over 18 months from that original mind map to launch…

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Thoroughbred Sales Assessment; Update from the Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures, 2019

By Tom O’Keeffe

The Beaufort Cottage Educational Trust Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures took place this year at the National Horseracing Museum in Newmarket and a host of international and local veterinary specialists and industry leaders were present to discuss the veterinary aspects of the sales selection of the thoroughbred.

Gerald Leigh was a prominent breeder and racehorse owner until his death in 2002; and his friend and vet Nick Wingfield Digby opened the seminar and introduced the speakers. The Gerald Leigh Charitable Trust has established this annual lecture series to provide a platform for veterinary topics relating to the thoroughbred to be discussed amongst vets and prominent members of the industry.

Sir Mark Prescott described his take on the sales process and some of the changes he has noted since his early involvement in the industry. He recalled how the first Horses in Training sale he attended had only 186 horses. In those early days, his role was to sneak around the sales ground stables late at night on the lookout for crib biters. Back then, there was no option to return horses after sale, and as a result, trainers preferred to buy horses from studs they were familiar with—a policy Sir Mark still follows to this day.

Sir Mark went on to explain that he believes strongly that the manner in which an animal is reared has a strong bearing on their ability to perform at a later date. Sir Mark also mentioned that horses can cope with many conformational faults nowadays that would have been deemed unacceptable in his early years. He attributed this to improvements in ground conditions, such as watering and all-weather surfaces. Mike Shepherd, MRCVS, of Rossdales Equine Practice in Newmarket had been tasked with describing and discussing the sales examination from a veterinary viewpoint and in particular attempting to define what vets are trying to achieve in this process.

Shepherd’s key message was that the physical exam is the cornerstone of any veterinary evaluation. A vet examining a horse on the sales ground is not a guarantee that the horse will never have an issue—there is no crystal ball. Owners and trainers should be aware there are several limitations of the vetting process, and it is helpful to think in terms of a “pre-bid inspection” rather than a “pre-purchase examination”. The horse is away from its home environment, and this puts a lot of stress on the animal. In most cases, pre-purchase exercise is not possible, so conditions that are only apparent when the horse is exercising and in training may go undetected.

Time is a major challenge, with both vendors and prospective purchasers pushing for everything to be done as quickly as possible. A busy sales vet may have a long list of horses to examine, and information on each must be transferred to their client coherently and clearly—all before the horse is presented for sale. It can be challenging to acquire a detailed veterinary history. Previous surgeries, medication and vices displayed by the animal ought to be reported, but in many cases the person with the horse is not in a position to accurately answer questions on longer-term history.

Everyone involved—the vendor, the prospective purchaser, and the auction house—wants the process to go ahead. The horse to be bought/sold and the vet can be seen as a stumbling block. Prospective purchasers may want the horse to be examined clinically, its laryngeal function examined by endoscope, radiographs of the horse’s limbs either reviewed or taken, ultrasound examinations of their soft tissue structures and heart performed. The role of the vet is to help the purchaser evaluate all this information and make an evidence-based decision on whether to purchase the horse.

Examining vets can face conflicts of interest when examining horses that are under the ownership or care of one of their clients. Shepherd explained how Rossdales, and some other practices involved in sales work, have a protocol that an examining vet will not perform a vetting on a horse in the care of one of their own clients, and will disclose to the prospective purchaser if the vendor is a client of the practice. It is crucial to avoid working for both buyer and seller as a conflict of interest becomes unavoidable.

It is also essential that the vet understands exactly what the horse is expected to do following the sale. Thoroughbred horses in flat racing have short timescale targets and, as a result, certain parts of the examination carry more weight than others. For example, the knees and fetlock joints are commonly implicated in lameness in flat racehorses; thus particular attention must be paid to these joints when examining yearlings. Soft tissue injuries are impactful in all young thoroughbreds, but there is a particular emphasis on tendon integrity in the National Hunt racehorse because career-threatening tendon injuries are particularly prevalent in these horses. When evaluating potential broodmares, good feet are very relevant, and overall conformation is particularly important if the aim is to breed to sell. Vetting horses for clients aiming to pin hook their purchases places different requirements on the examining vet. These horses need to be able to cope with the preparation required for another sale, and they must also stand up to the scrutiny of vets at a later sale. The horse’s walk and conformation rank high in the foal/ yearling stage but may be judged to be less significant if the horse breezes in a fast time at a breeze up sale.

It is also critical that purchasers recognise that many of the common veterinary issues encountered in training are not detectable at the Sales stage. …

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

How the digestion of nutrients may improve horses’ overall condition

By John Hunter

The importance of breeding and training are well established, but there are many differences in the way yards prepare their horses. For several years our group—a trainer, a vet, and a physician specialising in nutrition and the gut—have been working to see if we could improve equine health and performance using a scientific approach.

The aim has been to explore ways in which the biochemistry underlying the digestion of nutrients might improve horses’ overall condition. In some cases this involved applying developments in the field of human nutrition to horses. In others we have tackled well-established problems within equine physiology.

Beetroot juice supplementation

Beetroot is a rich source of nitrate and is frequently taken by athletes to improve their performance. Nitrate produces nitric oxide, which dilates blood vessels, thus reducing blood pressure, increasing blood supply and promoting glucose absorption, and potentially increasing the energy available for high-speed exertion. However, not all athletes appear to benefit, and there had been no study so far on the effect of beetroot juice in horses.

Twenty racehorses (colts and geldings) in full training were divided into two groups. All were fed their standard diets. One group received beetroot juice with a sweetener to mask the taste and the other a sweetener only for four weeks. After four weeks, nitrate levels in the blood were measured and compared to the starting levels. The level of nitrate rose very slightly in the test group, but no change in performance or condition was noted in any of the horses. Beetroot juice does not seem to help horses.

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is important, not only for preventing anaemia and maintaining the health of the nervous system, but also because it produces enzymes which are crucial for allowing the entry of nutrients into the biochemical cycles producing the main source of energy in both man and horse: ATP. In humans, B12 is derived from eating meat, fish and dairy products. Horses and other herbivores, obtain their vitamin B12 by ingestion of cobalt from pasture which is then used by intestinal microorganisms to form the vitamin. As racehorses are rarely turned out on pasture, most feed concentrates are supplemented with B12.

‘As the intensity of work increases, the composition of the diet and the amount of food consumed change as a consequence of the increased consumption of starchy cereal grains. This will alter not only the dietary supply of B vitamins but also the intestinal synthesis…and it is an open question whether the rate of their absorption is exceeded by tissue demand when horses are in intensive training’ (Frape 2010, p250).

The amount of soluble carbohydrate in the diet of the racehorse must be carefully regulated. ‘Racehorses on a high-concentrate/low-roughage diet and little access to grazing are to some degree already on a metabolic knife-edge’ (Ramzan, 2014, p258).

The trainer was concerned that a number of horses in his yard were below par from the start of the Flat season as their appearance and performance were disappointing. Their diet was unchanged, but they ate poorly and failed to regain weight after racing. Veterinary investigations, including full blood screening, failed to reveal any cause.

As lethargy and early fatigue are two of the earliest symptoms of B12 deficiency in man, it was decided also to check the B12 status of the horses affected. Twenty racehorses, which were out of condition, were identified and divided into two groups. Blood samples were taken, and B12 levels were recorded. One group was supplemented with B12 injections at 3mg twice weekly for three weeks (18mg in total). The other group acted as controls. At the end of that time, the horses’ condition was reassessed by the trainer on his return from a week’s absence.

The concentration of vitamin B12 in the 20 horses was found to lie within the normal range and was slightly greater than that found in healthy yearlings on pasture at a local stud. After B12 injections, the level rose significantly. A further determination later in the season showed that this initial increase had disappeared. Overall there was no difference between the blood levels of B12 at the end of season compared to the beginning. Changes in B12 concentration, however, did not affect performance. The trainer, who was not informed which horses had received B12 supplements, considered that 8 horses had improved and 12 had not. These were equally distributed between the two treatment groups, and those considered to have improved did not have higher levels of B12.

Thus, despite previous anxieties, racehorses on standard diets have normal B12 levels which remain satisfactory throughout the season. Supplementary injections increase blood concentrations temporarily, but there was no correlation between blood B12 concentration and performance.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Trainer Profile: Kevin Prendergast

By Lissa Oliver

“The best horses are the best bred”, says Kevin Prendergast; and he should know. Right now, he’s watching a potential champion walk quietly past. Madhmoon has yet to win this year, but having finished fourth in the 2000 Guineas and second in The Derby, a win isn’t likely to be long in coming. Prendergast trained his dam, Aaraas and grand dam Adaala, both winners, and a long list of their siblings and progeny, too. No less than My Charmer, dam of Seattle Slew, is the fifth dam of the Friarstown Stables star.

Much like Madhmoon, Prendergast, who will be 87 this July, can also boast an illustrious line. He has followed in the footsteps of his grandfather, Patrick, and father, the renowned Paddy ‘Darkie’ Prendergast; as have his brother Paddy Jr and nephew Patrick, the latter recently joining forces with John Oxx in a dual-venture new to Ireland.

Innovation was nothing new to ‘Darkie’, who pioneered trans-Atlantic travel for racehorses and remains to date the only Irish trainer to become Britain’s Champion Trainer three years in a row. “It will never be done again”, says Prendergast, who took out his own training licence in 1963—the year his father won the first of those titles. Up until then, Prendergast had been working with his father as assistant trainer.

“It was the logical thing”, he says now of his decision to go out on his own. “I had always wanted to be a trainer. It’s a labour of love more than a job. There are more ups than downs. The good days are great days, but at the same time the bad days are very bad.

“I don’t know if starting out on my own was made easier because of my family background or harder, because I’ve never had to do it without that background”!

He may have learned a lot from his father, but Prendergast also gained a wealth of experience during a five-year stint in Australia, where he ventured in 1949 as a 17-year-old. The connection had started much earlier, however, as it is where he was born while his father was riding there.

“I was assistant to Frank Dalton; he had a very successful stable at the time”, recalls Prendergast. Indeed, during his time with Dalton, some of the country’s top prizes fell their way, with horses such as Oversight and Barfleur. “I wouldn’t say the methods of training were any different out there”, he notes. “Methods are basically the same for everyone. But they were so far ahead. Even then, all the tracks were watered, whereas in Ireland they were building a facility at the Curragh and forgot about the water! There was no thought given to how they would get water onto the track.

“I left Frank Dalton to come back home again in 1954, to work with my father. I was riding as an amateur then, too. I was assistant to my father for eight years”.

There was no shortage of top-class horses in his care at Darkie’s, and in 1960 Martial became the first Irish-trained winner of the English 2000 Guineas, in the same year that the stable saddled Alcaeus and Kythnos to finish second and third in the Epsom Derby. Prendergast has gone on to have seven runners in the great race—Madhmoon going tantalisingly close this year.

Mahdmoon

Setting up on his own, Prendergast got off the mark quickly when Zara won at Phoenix Park in May 1963—the victory all the sweeter because he was also the winning jockey. He had bought Zara, described as “a bit of a monkey”, from his father; and it wasn’t long before he stepped out of Darkie’s shadow to establish himself as a Classic-winning trainer.

Like Zara, Pidget wasn’t easy to train, but Prendergast knew how to get the best from the filly, and she provided the first two of his eight Irish Classics, taking the Irish 1000 Guineas and Irish St Leger in 1972, as well as the Pretty Polly Stakes. The following year Conor Pass gave him a back-to-back Irish St Leger win, a feat Prendergast repeated in 1996 and 1997 with Oscar Schindler. In 1977, Nebbiolo provided him with an English Classic when landing the 2000 Guineas.

There are not too many trainers blessed with the skill and longevity to boast a 40-year gap between their first Irish 2000 Guineas winner and their most recent, but Northern Treasure (1976) and Awtaad (2016) are testament to Prendergast’s vast experience.

“There’s no secret to it, we all want the same thing”, he says of that skill. “Just keep them healthy and happy”. When Tell The Wind gave him his landmark 2,000th winner at Dundalk in 2010, it was as good a proof as any of a healthy happy stable.

Friarstown Stables are conducive to contentment. Just close enough to the bustle of the Curragh to avail of the world-class facilities on the doorstep, yet tucked quietly away from the main thoroughfare, providing a little slice of peace and tranquillity. Mature trees shelter the farm and its fields, and private grass and all-weather gallops nestle imperceptibly in pastureland, protected by natural hedgerow.

Natural is the operative word. This is a working stable with traditional boxes, well-maintained and tidy, certainly, but with no airs and graces. Functional, not showy. Prendergast is very much stamped upon his surroundings.

For a successful yard, he has always kept a relatively small string. He has 35 horses and a small team of staff, who go about their work with quiet efficiency. There are no shouts or raised voices, but lots of laughter. Even first lot, keen to stretch their legs and get out, match the calm mood. There’s no skittish behaviour, no wilful shows of temperament, and each of the nine horses walk by on a long rein, perfectly settled.

“He has a bit of temperament, which Awtaad never had”, Prendergast says of Madhmoon, who is in the first lot and on best behaviour. “I was never worried about him training on at three as we’d looked after him. It’s the busy two-year-olds you’d worry about. He does everything right and he’s a good horse to work—you can set your clock by him. I trained the dam and the grand dam; I’ve had all the family here. He’s never been away from here since he arrived at two and I see him every day.”

Methods might be the same the world over and he might not be one for new technology, but therein lies the secret to Prendergast’s success. Observing the individuals and retaining a familiarity with the families that go back several generations. Much of that is owed to the loyalty of owner breeders such as Lady O’Reilly and Sheikh Hamdan Al Maktoum, for whom Prendergast has trained for over 30 years.

“I’m very, very lucky to have good owners like Lady O’Reilly and Sheikh Hamdan”, Prendergast acknowledges. “They have been with me for a long time and so have my Irish owners. Unfortunately, Ireland is losing a marvellous owner because conditions in France are so much better. The prize money is good and then there are the bonuses; it’s hard for us to compete. We tried to get a Tote monopoly here—my father tried hard. Australia, France, New Zealand, America—they all have a thriving Tote.

“Trainers are getting run out of it. the €2,000 or €3,000 we’re running for doesn’t pay for the horsebox to get them there. Trainers are giving up in England every day. It’s all to do now with agents and how well a horse is bred; everybody wants black type, but at the other end there are not too many races for horses that cost €72,000 or less. It puts the smaller fella out of the game. They don’t look after the smaller trainer, and it’s the smaller trainers who are the backbone of the game. If you lose them, you may as well close the whole game down”.

He has seen many changes during his career and suspects some may be for the worse—too often a case of, “Common sense gone out the window”. He smiles at the idea of giving horses Guinness or eggs: “That’s something in the past. Nowadays you’d be afraid to give them spring water”. But there’s an edge to the joke.

Like many, he feels the IHRB is too quick to follow the BHA and the equine flu scare was a case in point. “We had immunised our horses at Christmas, and then we were forced to get them done again. It made them ill, and we lost the early part of the season”.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Hindsight : Andreas Löwe

By Peter Mühlfeit

His career as a trainer ended in style: With a winner in Dortmund just after Christmas in 2016. Thirty-five years earlier he had opened his account with his first runner Adita in Cologne, where he is still based. In between, Andreas Löwe collected 1,163 wins on the flat plus 25 over the jumps. Five individual Gp1 winners stand out, and he won seven Classic races. For his owners he earned almost €16 million in prize money. Löwe started his racing passion as a jockey at the famous Gestut Ravensberg, but was too heavy for a professional career. Löwe then became stud manager before turning to training. Peter Muhlfeit spoke to Andreas Löwe about his career and life today.

AL: I haven’t really stopped working with horses. I’m an adviser and racing manager for Gestut Gorlsdorf and Gestut Winterhauch, in any capacity I’m needed. To stop completely would have made me sick, as my wife and I love to be around horses; and we like to travel to the sales and the races. Since the 1960s, I practically have been in the horse yard every day. I couldn’t just switch off the engine. Luckily my wife who had shared that passion all along, still thinks the same. Otherwise it would not have been possible.

How are the Gorlsdorf and Winterhauch stables performing this season?

Gorlsdorf had a Listed winner at Baden-Baden with the Sea The Moon-Filly, Preciosa. That was a very promising run. I’m sure there is more to come from her as she is only three years old and raced very lightly. She was in the ring during the Spring Sales the day before the race, but luckily she didn’t find a buyer. Gorlsdorf has about 20 horses in training. There are some good two-year-olds, but it’s early days. Winterhauch was a bit unlucky with plenty of injured horses, but we are hoping for a much better second half of the season.

As a trainer you won twice the German Oaks and four times the German 1000 Guineas. Were you particularly good with fillies?

I have been asked that a lot. But to be honest it had a lot to do with the fact that I often had more fillies in the stable than colts. A few decades they were much cheaper to buy, and we always had to look for budget opportunities. But I have to admit, I always had fun training fillies as they are often more sensitive than the colts and need a different approach. Mystic Lips was very special as she won the German Oaks like almost no other. I picked her at the BBAG Yearling Sales in 2005 for Stall Lintec. And Lolita, winner of the German 1000 Guineas, was a very sensitive filly. She was bought at the BBAG Spring Sales in 2003.

You also trained a lot of good colts. Name some of your favourites!

Amaron, a Group winner from two to seven years, impressed me the most. I bought him at Tattersalls December Sales in 2010 for Winterhauch. He was so consistent in his form. Just like Lucky Lion he won a Gp1 race. But Lucky Lion, runner-up in the German Derby and another one I bought for Winterhauch (this time however at the BBAG Yearling Sales) was a very difficult horse. So to win with him made me very proud.

Mystic Lips with Andreas Helfenbein and trainer Andreas Löwe, after winning the Henkel Prize of Diana 2007.

In the early days it was Protector I liked best as he performed successful on Group level for eight years, winning two Gp2 races. He was also the first German horse to be invited to the International Races in Hong Kong. He finished fourth in the then Gp2 Hong Kong Vase in Sha Tin.

What about the jockeys—who in particular did you like to work with?

With Andreas Helfenbein I had a lot of success, also on top level. He won the Diana (German Oaks) for me on Mystic Lips for example. But it has always worked well for me and my owners not to stick to one particular jockey, but to look around who is available and who would be the best to ride the horse.

You picked a lot of your winners at the sales for your owners. Where were your best hunting grounds?

Kings Bell with trainer Andreas Löwe.

I’m still acting as a thoroughbred agent if someone wants me to buy a horse for them. In the past I obviously had a good range of owners who asked for my advice. I guess I was pretty successful in Newmarket. I always liked the December sales as the prices were much in the budget range of my owners. You could get some good buys there. For me, the looks of the horse is very important—the first impressions—to see how the horse presents itself. Usually you see rather if it has character. And that’s very important.

For example Sehrezad—his story is rather unusual, isn’t it?

Holger Renz, a longtime racing owner, had the idea to buy a horse at Newmarket together with some friends. They asked me for advice, but the sales catalogue contained about 2,000 horses. So we decided to make a preselection by considering only the horses born on the 22th of April, the birthday of one of the partners. There were forty horses with that birth date and I immediately fell for Sehrezad, who became the top miler in Germany in 2010. He won three Group races.

You have travelled a lot. Where do you like it best?

I’m anglophile. Newmarket is wonderful; the British people in general are very hospitable. I love racing in Epsom or Ascot, and we used to have runners there with some success. Italy had been our ‘El dorado’ through the years. We won a lot of big races, and they offered much more money than we got in Germany. But the situation now makes me rather sad. It’s a real shame if you think about the lovely tracks they have in Italy.

You have been involved in racing for more than five decades. What do you still find fascinating?

Needless to say, I love horses—their expression. They are such special animals. And I like to transfer the enthusiasm I have for these horses to my clients. Despite the fact that there is a lot of pessimism about the future of racing in Germany, in my circles, the people I’m dealing with I find plenty of enthused voices who are hoping for a better future of racing and are willing to invest in that future.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Tech advances - opportunities for trainers

By Alysen Miller

From heart rate monitors to GPS trackers, smart treadmills to light masks and even Artificial Intelligence, a plethora of new technologies has breezed onto the market in recent years, all claiming to offer trainers an edge in a sport where every pixel in a photo finish counts. And it’s not just on the gallops where their impact is being felt; everywhere from the barn to the breeding shed, a raft of new gadgets is quietly powering a technological revolution that has the power to reshape the racing industry. So in this brave new world, how do trainers ensure that they are exploiting every possible technological advantage at their disposal in their quest to leave no margin left ungained?

The reality is that, in an increasingly data-driven world, racing has been ironically slow to catch on to technologies that have already become mainstream in sports ranging from running to cycling. Every MAMIL (middle-aged man in lycra) worth his electrolyte gel has his own GPS tracker fitted to his carbon fibre bike. Now, companies such as Arioneo and Gmax are helping the racing industry catch up to the peloton by providing real-time exercise data, allowing trainers to track horses’ speed, cadence, sectional times and stride length, as well as heart rate and other biometrics using a device fitted to the horse’s girth. These data are then fed back to an app, allowing every aspect of the horse’s work and recovery to be assessed.

Lambourn-based husband and wife team Claire and Daniel Kübler were easily adaptable to the cause. “We did a lot of research when we started training, going, “OK, what’s out there to actually put a bit more science behind what people do”? There’s so much data, so the more you can have, the better decisions you’re going to make”, explains Claire. “I started graphing out the data that we gathered, looking at frequency of stride to see where horses [and trip] correlate. It has actually helped to pinpoint when a horse does want a distance or it when it wants dropping back to a more speed trip. So it was really useful to help decide which way to go”.

Horse wearing a heart rate monitor and GPS tracker.

Armed with a degree in Natural Sciences from Cambridge University, Kübler realised that the concept of marginal gains (European Trainer - December 2015 - issue 52) was as relevant to the racing industry as it was to other sports. Popularised by Sir David Brailsford—the erstwhile head of British Cycling and latterly doyen of professional cycling behemoth Team Ineos (formerly Team Sky)—the theory of marginal gains states that if you break down every element you can think of that goes into the performance of an athlete, and then improve each element by 1%, you will achieve a significant aggregated increase in performance.

“The optimum is getting 100% out of a horse. But for us, every little bit of marginal gain can hopefully get the most out of each individual”,

Artificial Intelligence (AI) may conjure images of a dystopian future, but it is already being used in technologies available to trainers in the United States and Canada. Billed as the world’s first ‘smart halter’, or headcollar, Nightwatch was developed by Texas-based Protequus to monitor horses while they are in their stables overnight. “Unlike a lot of other wearables, this technology is based on an AI platform, which means that it learns every animal’s unique physiology and looks for deviations in that physiology that correlate with pain or distress and will send a text, phone and email to you so you can intervene at the earliest signs of a possible problem”, says the company’s Founder and CEO, Jeffrey Schab. The company is aiming to make Nightwatch available to European consumers by 2020.

If the worst does happen, a host of companies are harvesting the latest tech to aid in pain management and rehabilitation. Among these is the ArcEquine, a wearable brace that delivers a microcurrent to aid in the repair of soft tissue injuries by increasing levels of Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) within affected cells. While the benefits of water therapy and treadmills have long been recognised by trainers, the latest gadget from ECB is a smart water treadmill that essentially functions as a Fitbit for horses. Not only does it incorporate salt- and cold-water functions as well as an incline feature, the treadmill comes with a built-in computer that allows the user to set programmes for particular horses, while feeding this data back to a phone or tablet for analysis. “By playing around with speed, water depth and incline, you can target specific muscles, control the heart rate, dictate the horse’s stride length and work on the horse’s straightness,” says Richard Norden, sales and marketing manager.