Remembering Hollywood Park - Edward “Kip” Hannan and the Hollywood Park archive

By Ed Golden

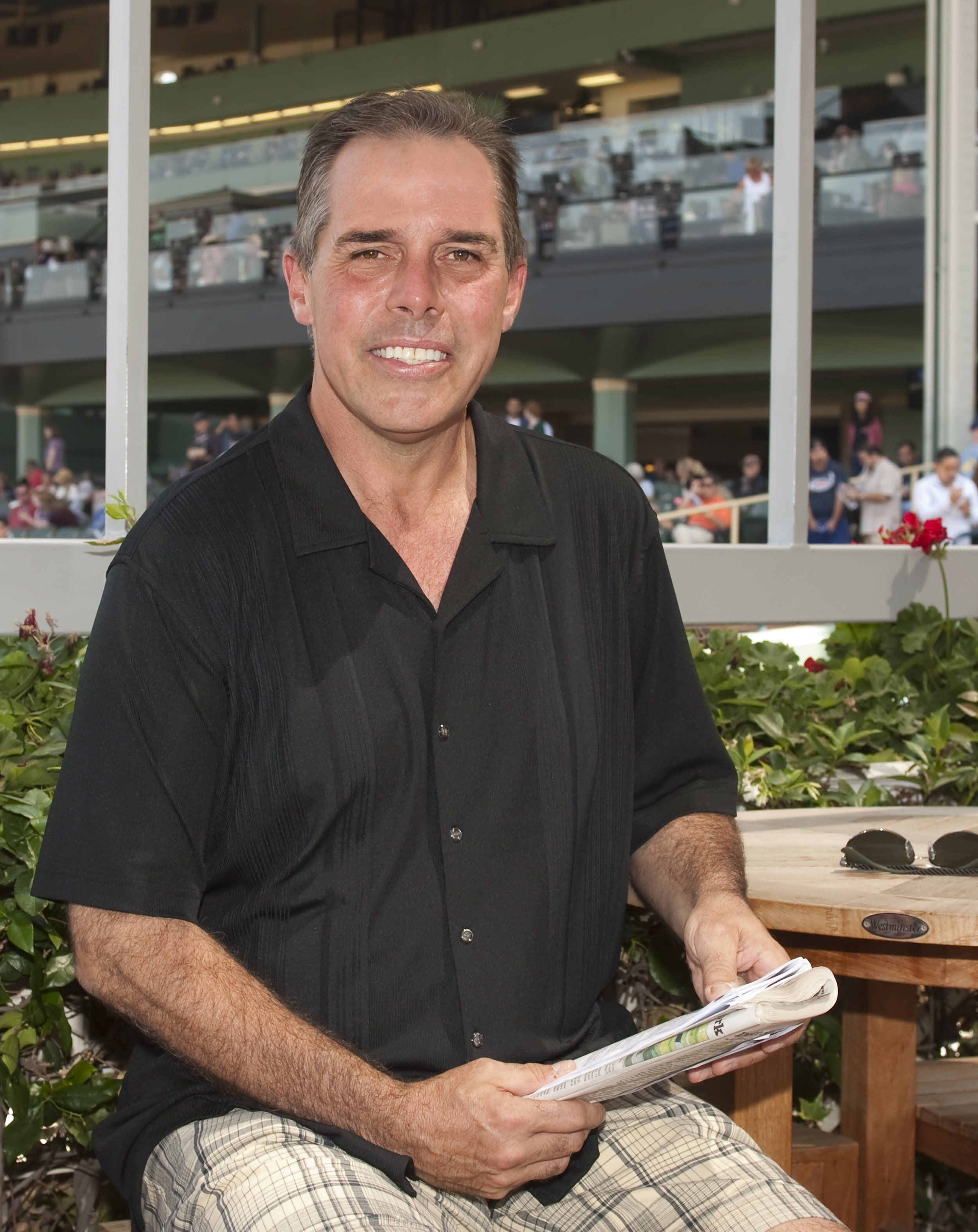

In an age of “Races Without Faces,” Edward Kip Hannan is a renaissance man.

Kip Hannan outside of UCLA’s Royce Hall

Not to be confused with an anarchist bent on destroying history’s truths, Hannan is an archivist, with an ethos dedicated to preserving timeless treasures and ensconcing them in pantheons for future generations.

With the artistic and obdurate passion of a Michelangelo, when Hollywood Park closed forever on Dec. 22, 2013, like a man possessed with an oblation, Hannan knew there was “gold in them thar hills” and dug in like he was assaulting the Sistine Chapel.

Far from a fool and capitalizing on today’s applied sciences, Hannan has successfully transitioned through more than four decades, surviving—yea, overcoming—a concern once epitomized by Albert Einstein who said: “I fear the day that technology will surpass our human interaction. The world will have a generation of idiots.”

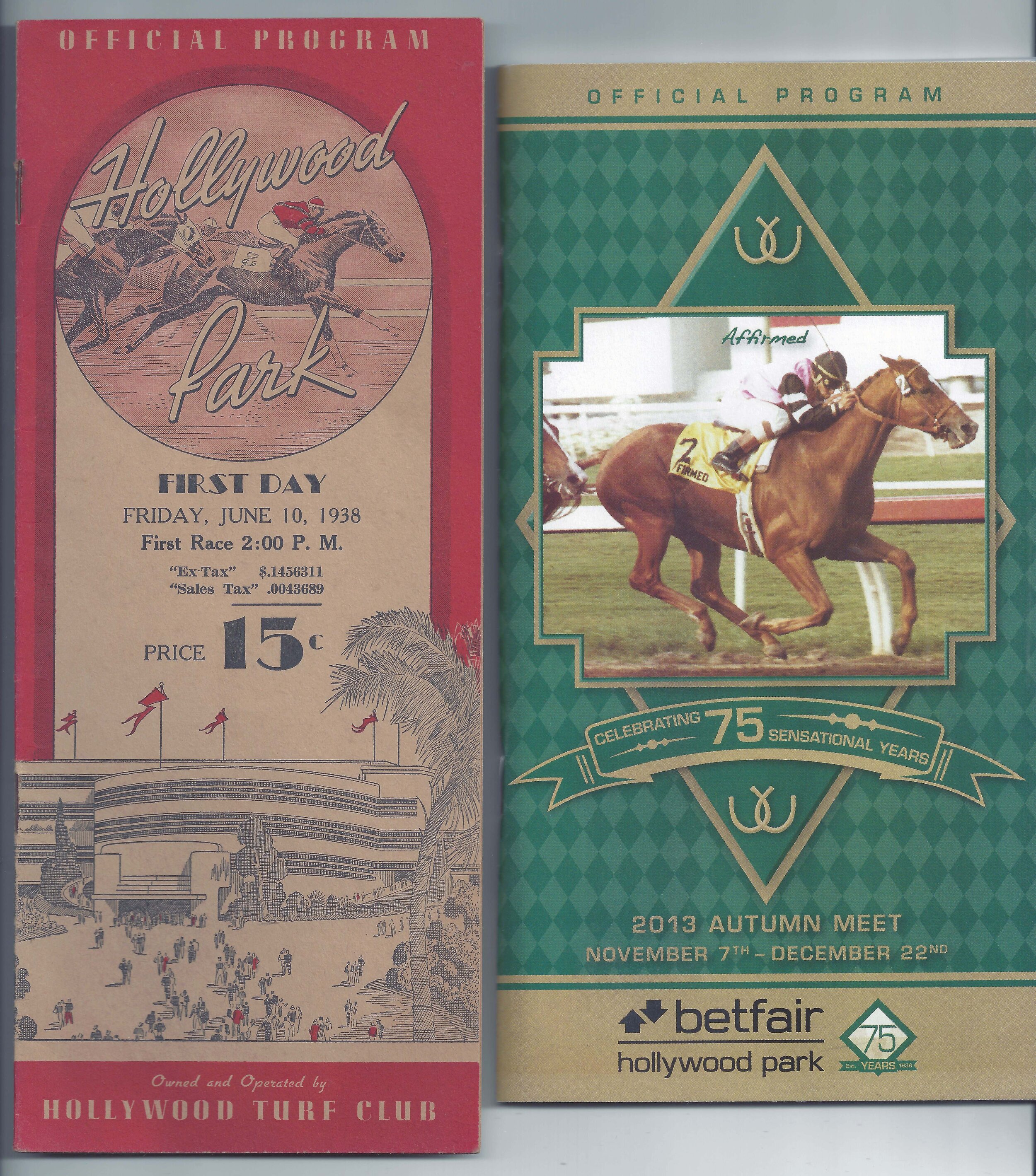

Hannan made it his mission to rescue archives from the Inglewood, Calif. track that opened 75 years earlier on June 10, 1938. The Hollywood Turf Club was formed under the chairmanship of Jack L. Warner of the Warner Brothers film corporation.

Hollywood Park Opening Day and Closing Day programs.

Among the 600 original shareholders were many stars, directors and producers of yesteryear from movieland’s mainstream, including Al Jolson, Raoul Walsh, Joan Blondell, Ronald Colman, Walt Disney, Bing Crosby, Sam Goldwyn, Darryl Zanuck, George Jessel, Ralph Bellamy, Hal Wallis, Wallace Beery, Irene Dunne and Mervyn LeRoy.

They pale, however, compared to the equine stalwarts that raced at Hollywood Park, which include 22 that were Horse of the Year: Seabiscuit (1938), Challedon (1940), Busher (1945), Citation (1951), Swaps (1956), Round Table (1957), Fort Marcy (1970), Ack Ack (1971), Seattle Slew (1977), Affirmed (1979), Spectacular Bid (1980), John Henry (1981 and 1984), Ferdinand (1987), Sunday Silence (1989), Criminal Type (1990), A.P. Indy (1992), Cigar (1995), Skip Away (1998), Tiznow (2000), Point Given (2001), Ghostzapper (2004) and Zenyatta (2010).

Hannan obviously had his hands full, but thrust ahead undeterred as he soldiered on to digitize Hollywood Park’s entire film/video history of nearly 4,000 stakes races for eventual public access.

It seemed a mission mandated by a higher power.

Hannan, who turns 57 on Jan. 29, was born in Phoenix, Ariz., where his mother and father had come from Brooklyn. Moving to California when he was just two, they lived on the Arcadia/Monrovia border within a couple miles of storied Santa Anita, and left in 1972 for nearby Temple City where Kip has lived ever since.

In 1979, at the tender age of 15, he began working as a marketing aide at Santa Anita under the aegis of worldly racing guru Alan Balch and his fastidious publicity sidekick, Jane Goldstein.

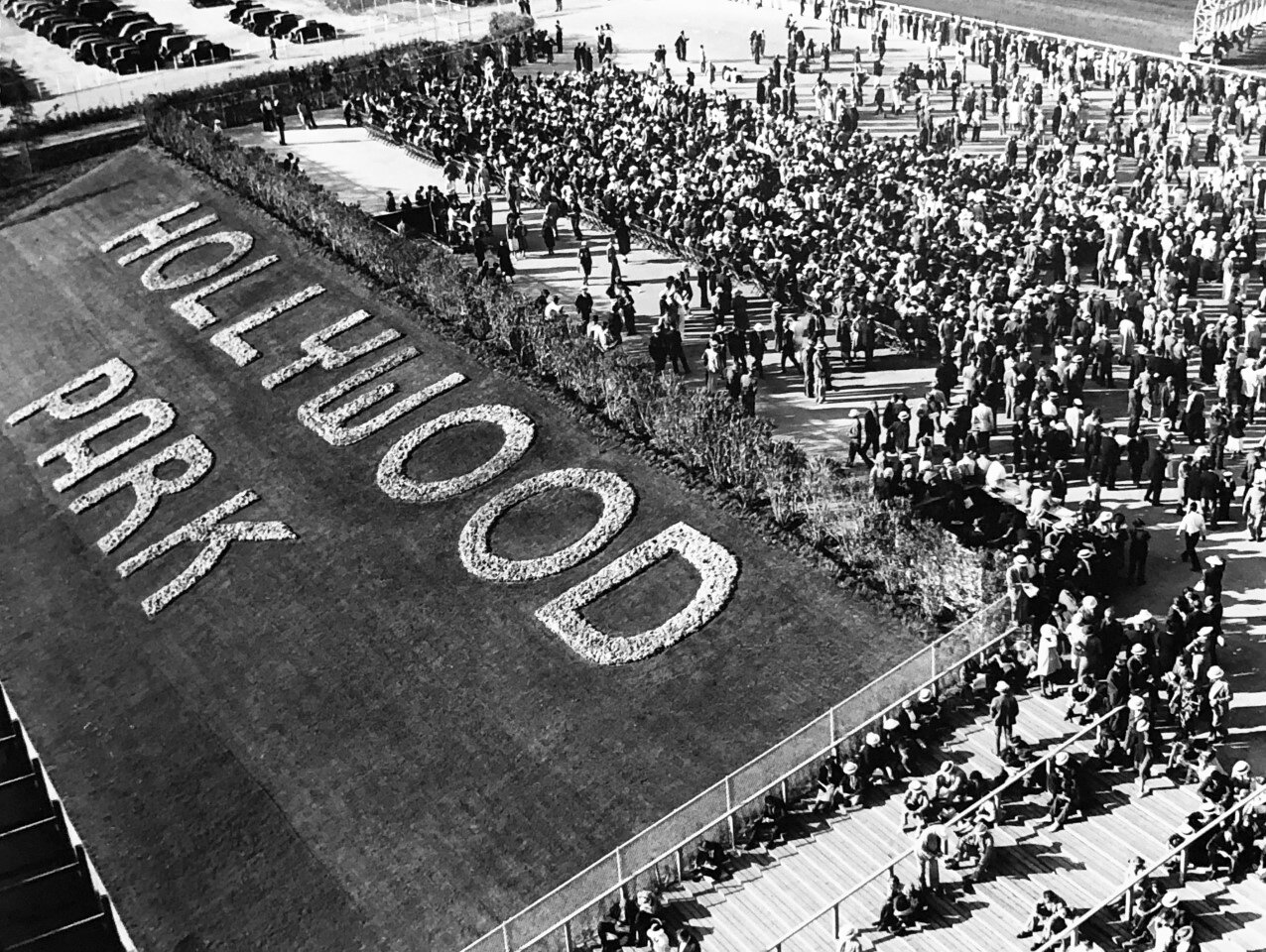

Hollywood Park, 1939.

He was the last employee at Hollywood Park in order to organize archives for digitization and eventual transfer to the UCLA Library, where he began working in late 2014 as videographer and editor. He is still employed there, maintaining the integrity of Hollywood Park film, video, photo and book archives.

Hannan sums up his career in one word: “Fascinating.”

“I had already started collecting music at age 11, in 1975,” Hannan said, “and probably because of this, I associate many life events with the music of the time. I’m sure many people can relate.

“It was at Santa Anita where and when I first met Lou Villasenor, who was already working there and would go on to become a staple of its TV broadcast team—a job he held for nearly 35 years before his death in 2018.

“Lou became one of my best friends and eventually was the one who brought me to Hollywood Park where I was hired to work in its television department in 1986.”

As marketing aides, their tasks were menial and labor intensive, such as removing duplicates from mailing lists, organizing contest entry cards filled out by fans, and other simple office-related duties. After a few years, Hannan was promoted to supervisor.

At Santa Anita in 1982, Hannan met another new hire who became an instant best friend: Kurt Hoover, current TVG anchor whose relaxed and ingratiating on-camera presence is the stuff of network standards. He also is a devoted and skilled handicapper and a successful horse owner.

“We hit it off immediately,” Hannan says.

A couple years later, Hannan left Santa Anita briefly to study television production at Pasadena City College, while also finding time to work at Moby Disc Records in town.

Burt Bacharach and wife Angie Dickinson admire their race horse Apex II in his Hollywood Park stall, 1969.

“I had always been a movie buff, with the original 1933 ‘King Kong’ my inspiration, along with ‘One Million Years B.C., and not just because of Fay Wray and Raquel Welch—although I had crushes on both. It was the dinosaurs and the stop-motion filmmaking and special effects.

“I wanted to get into film somehow but couldn’t afford USC, so the gateway was video/television production, first in high school and then at Pasadena City College.

“It was around this time, summer of 1985, that Santa Anita contacted me out of the blue,” he said. “Knowing I had radio operation training in college, they told me of a radio station in the planning stages that would be an on-site source for racing fans and handicappers broadcasting information throughout the day.

“Nearly doubling my hourly wage from the record store, I jumped at the chance. It was designed and organized by the same company that created the low-power AM radio station that can be picked up near the LAX Airport for flight information; and soon, KWIN Radio AM was created.

“I was the operator/engineer with countless marketing people and handicappers available for on-air hosts and guests. It was at this time I met Mike Willman, the ‘roving reporter’ and program manager of sorts, who gathered interviews on his cassette recorder for us to air.

“On April 23, 1986, Villasenor took me to Hollywood Park where he was program director and graphics operator in its TV department.

“I was fortunate to be there and was in the right place at the right time. They were short of cameramen that day, and word came from Hollywood Park President Marje Everett that many of her personal friends would be attending, including popular celebrities of music, film, television and politics.

“The TV department was to capture ‘Opening Day Greetings’ from them on their arrival. The TV director asked if I could handle the professional portable camera, portable tape deck and tripod. I said yes, gathered up everything, and headed to the Gold Cup Room, avoiding crowded elevators with all that gear.

“It was then I realized my career was moving up, for at that moment, not three steps behind me on the escalator were Elizabeth Taylor and Michael Jackson. As we continued to climb, all I could think of was getting to a phone to tell my folks how my first day went, before it had even started!

Michael Jackson and Elizabeth Taylor, 1986.

“There is one particular snapshot taken in the Gold Cup Room that I cherish. I’m not in the photo but was about six feet ahead of them, walking with my gear like I was on top of the world at age 22.

“I did get Michael Jackson’s autograph later, as miraculously he only had one bodyguard with him that day. At the time, there was not a bigger pop music star on the planet, and it was surreal to see him right before me.

“Even though they both declined to appear on camera for a greeting, it was Elizabeth Taylor who got to me. As I set up my camera gear not 25 feet from where she was sitting (and momentarily alone), she glanced up from the table and looked directly at me with this big smile.

“I literally melted! As I continued to fumble getting the camera onto the tripod, I kept thinking, ‘Dear God, those eyes!’ and I was ready to sign on for husband number seven, as suddenly it had all made sense to me. …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents

ISSUE 58 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 58 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - ONLY $24.95

Remembering - Seattle Slew - 1977 Triple Crown winner

By Ed Golden

All photographs published by kind permission of Hollywood Park archive

Bob Baffert was a young pup of 24, fresh out of college about to make a name for himself training Quarter horses at outposts in Arizona like Sonoita and Rillito when Seattle Slew became the first undefeated Triple Crown winner in 1977.

Forty-one years later, in 2018, Baffert followed suit, deftly leading Justify successfully down racing’s Yellow Brick Road to become only the second undefeated Triple Crown winner in history.

Now 67, the most recognizable trainer on the planet is a two-time Triple Crown winner (American Pharoah in 2015), and had the fates allowed, could have been a four-time winner, save for Silver Charm losing the 1997 Belmont Stakes by a length and Real Quiet by an excruciating nose the very next year in a defeat that smarts to this day.

Still young at heart four decades after he began his career, Baffert has fond memories of Seattle Slew, who became one of racing’s giants despite being purchased for the miniscule sum of $17,500.

“I was 24 and still in college I think, but I saw Seattle Slew win the Derby, the Preakness and the Belmont on TV, even though I wasn’t into watching a lot of Thoroughbred races,” Baffert said. “I was still a Quarter horse guy.

“But when I saw him run, I knew the name, and it was a great name—one that stuck with you.

Seattle Slew in the stable area at Hollywood Park,1977.

“He was a most impressive horse, especially because in the paddock, he looked completely washed out but would run a hole in the wind.”

He would use up so much energy before a race and still destroy the opposition; and that’s a trait he throws (in his bloodlines).

“He ran as a four-year-old at Hollywood Park and got beat, and then I quit watching him because I lost interest after that. But to me, he was one of the greatest horses I ever saw run on YouTube.”

***

The following story is about Seattle Slew: part Seabiscuit, part Secretariat. It was published on May 14, 2002, but is appropriately resurrected here in advance of this year’s altered Triple Crown.

This is an exclusive firsthand interview the author obtained with the late Doug Peterson—a bear of a man who trained Seattle Slew in his four-year-old season and who provided a Runyonesque tale of the horse and those closest to him before his untimely death of an apparent accidental prescription drug overdose on Nov. 21, 2004 at age 53.

Seattle Slew being saddled in the paddock before the Swaps Stakes at Hollywood Park, 1977.

(Reprinted courtesy of Gaming Today)

Great race horses do not necessarily prove to be great stallions.

Citation and Secretariat were champions on the track, but each was a dud at stud. Cigar was a king on the track but fired blanks in the breeding shed. He was infertile.

But one Thoroughbred that succeeded on both fronts was Seattle Slew, who in 1977 became the only undefeated horse to win the Triple Crown.

One of racing’s all-time bargains as a $17,500 yearling purchase, Seattle Slew died last Tuesday in Lexington, Ky., exactly 25 years to the day of his Kentucky Derby triumph. He was 28 and still productive at stud, despite falling victim to the rigors of old age in recent years.

Seattle Slew in the stable area at Hollywood Park,1977.

His stud fee was $100,000 at the time of his death and $300,000 at its apex.

Here was a horse for the ages—the likes of which racing may never see again. Consider this: at two, he broke his maiden in his first attempt, and two races later won the Champagne Stakes; at three, he won the Derby, the Flamingo, the Wood Memorial, the Preakness and the Belmont.

At four, he won the Marlboro Cup, the Woodward and the Stuyvesant. He won the Derby by 1¾ lengths as the 1-2 favorite in a 15-horse field. Overall, the dark bay son of Bold Reasoning won 14 of 17 starts and earned $1,208,726.

Doug Peterson was a naïve kid of 26 when he took over the training of Seattle Slew from Billy Turner, who conditioned him for owners Karen and Mickey Taylor through the Triple Crown.

Now 50, Peterson is a mainstay on the Southern California circuit where he operates a successful, if nondescript, stable. But his memories of the great ‘Slew are ever vivid.

“I got Seattle Slew late in his three-year-old year, after he got beat by J.O. Tobin at Hollywood Park (in the Swaps Stakes),” Peterson recalled. “Billy Turner brought him out here, but he didn’t want to run him. As the horse was getting off the van and they slid up the screen door that was on the top of his stall, it fell down and hit him on the head.

“The day of the race he had a temperature. That’s why he couldn’t make the lead. There was no horse ever going to be in front of this horse, but despite the temperature, they ran him anyway because of all the hype and all the money and all the fans who wanted to see him. That’s what started the disagreement between the Taylors and Turner.”

Peterson got his chance to train Seattle Slew through a stroke of good fortune.

“I was in Hot Springs, Arkansas, sitting on a bucket,” Peterson said. “I was cold and down and out, and this girl—an assistant for another trainer—came by and told me, ‘If you’re going to make it big, you’ve got to go to New York.’ I packed up with two bums and went to New York.

“I got stables at Belmont Park on the backside of Billy Turner, but that was just a coincidence. Turns out, I was in the right place at the right time because Dr. (Jim) Hill was the veterinarian for Billy, and he came to my barn and I asked him to work on a couple of my horses.

“Dr. Hill recognized my horsemanship, and he and Mickey Taylor were buying 15 yearlings. They were going to need two trainers, and this is how the whole thing started. They said Billy would have a string and I would have a string. Well, before the next year, they fired Billy. …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

ISSUE 56 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 56 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - PRINT & ONLINE - ONLY $24.95

Gary Young

By Ed Golden

For a guy whose livelihood is based on calculations measured in milliseconds, Gary Young never seems to be in a hurry.

But he is a quick study with a quicker opinion, remindful of Woody Allen’s quip: “I took a course in speed reading and read War and Peace in 20 minutes.

“It’s about Russia.”

Gary Young’s life is about racing, and consummately longer than 20 minutes. It started when his parents took him to Arlington Park at the age of six, too young to realize it was chapter one of an engrossing biography.

Half a century later, Young is a respected fixture at the apex of his profession as a private clocker and bloodstock agent, providing information for a fee, winning the odd bet with his own dough, and earning sizeable chunks of change as a buyer or seller of young horses at the sales ring.

Sitting in an open box in the last row of the Club House on any given morning, Young has all the tools of a clocker’s trade at hand: binoculars, stop watch, pens, pencils, notepad, recording devices, the obligatory cell phone, snacks, liquid refreshment and other assorted paraphernalia.

He confirms for posterity the horses’ workouts into his recorder with the verbal rat-a-tat-tat of a polished auctioneer, not missing a beat.

His is a specialized sanctum. It has been thus for four decades now.

Born in Joliet, Ill., Gary grew up in nearby Lockport and got his first glimpse of major racing at Arlington Park in Arlington Heights, about 28 miles and a 30-minute ride from Chicago.

“My dad would take me to the paddock and point out certain things, like horses washing out,” Young said, recalling those halcyon days of yesteryear. “We saw horses like Damascus, Dr. Fager and Buckpasser run there. When I was 12 years old, Secretariat came to Arlington after he won the Triple Crown at Belmont in 1973.

“At that time, there was really big-time racing at Arlington Park. It started sliding later that decade, ironically after (owner) Marge Everett got caught bribing the governor to build a freeway from downtown Chicago to Arlington Park.”

It was there he linked his liaison with the Winick family—Arnold, Neal and Randy—Arnold being the most prominent of the trio in the Windy City area.

“Arnold was a really big trainer in Illinois,” Young said. “We’d see each other and I’d say hi to him. My parents (Cliff and Rachel) were weary of the Illinois winters and always talked about moving to Miami where Winick primarily was based.

“He told me if I ever came there to stop by and I could have a job. About 1978, we moved to Florida where I started at the bottom, walking hots and later grooming horses for Neal, who was trainer of the Winick stable there. Randy was training in California.

“As a groom, I became very aware that I was severely allergic to hay. The inside of my arms would burn like they were on fire if I filled up a hay net. Turned out, the Winicks always had someone who would go up in the grandstand and time horses, watch their horses work, watch other horses work, and make recommendations on ones to purchase or claim.

“Neal decided that because of my allergy, I couldn’t groom horses, so he bought me a stopwatch and sent me to the grandstand to time horses. It was in April of 1979 when I was 18. This past April marked 40 years I’ve been a clocker.”

During that span, Young has received testimonials from the game’s biggest players, among them Jerry Bailey and Todd Pletcher. Noted Bailey: “Gary Young has the unique ability to spot good horses at two-year-old-in-training sales after they come to the track to embark on their careers.

“Having watched him grow in racing from the bottom up, his foundation is rock solid and his eye for talent as good as any in the game.”

Added Pletcher: “Gary found Life at Ten for us. His record at auction speaks for itself. He commands respect in many aspects of the racing world.”

Young readily acknowledges he’s made more money buying and selling horses than betting on them, although his maiden triumph as a gambler remains fresh in his memory.

“The first horse I clocked and bet on that won was trained by Stan Hough, who was the dominant trainer in Florida at that time, along with Winick,” Young said. “It was the first horse that Hough bred, and it was named Lawson Isles. He paid $12 or $14.

“I thought to myself, ‘That’s pretty cool.’ Little did I know that I’d still be doing it 40 years down the road.

“I spent a couple years around Florida clocking, and in the fall of 1980, a horse came to our barn named Spence Bay that Arnold had purchased out of the Arc de Triomphe sale.

“He was the meanest horse you’d ever want to be around but also an unbelievable talent. He won a couple stakes in Florida like a really good horse, but Arnold always would cut back his stock there and around April, he sent some to California, including Spence Bay.

“California was California at that time, and I took the opportunity to come there with Spence Bay in April of 1981 and clock horses.

“I stopped working for the Winicks about 1983, but it was amicable, not bitter by any means. They were kind of downsizing a bit then anyway, and I basically went out on my own. I got my last steady paycheck around 1983, before I started clocking.

“Racing was really good in California at that time, and the Pick Six was very popular and appealing. I’d provide my information to Pick Six players for a percentage of the winnings, and I hit a lot of them in the 80s.”

Times have changed, however. “These days, I definitely make more money buying and selling horses than I do gambling,” Young said. “It’s not the same.”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

SUMMER SALES 2019, ISSUE 53 (PRINT)

$6.95

SUMMER SALES 2019, ISSUE 53 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

PRINT & ONLINE SUBSCRIPTION

From $24.95

Personal preference - training from horseback or the ground

By Ed Golden

At 83, when many men his age are riding wheelchairs in assisted living facilities, Darrell Wayne Lukas is riding shotgun on a pony at Thoroughbred ports of call from coast to coast, sending his stalwarts through drills to compete at the game’s highest level.

Darrell Wayne Lukas accompanies Bravazo, ridden by Danielle Rosier

One of three children born to Czechoslovakian immigrants, Lukas began training quarter horses full time in 1967 at Park Jefferson in South Dakota. He came to California in 1972 and switched to Thoroughbred racing in 1978. Rather than train at ground level as most horsemen do, Lukas has called the shots on horseback lo these many years, winning the most prestigious races around the globe.

A native of Antigo, Wisconsin, he was an assistant basketball coach at the University of Wisconsin for two years and coached nine years at the high school level, earning a master’s degree in education at his alma mater before going from the hardwood to horses.

His innovations have become racing institutions, as his Thoroughbred charges have won nearly 4,800 races and earned some $280 million. They are second nature to him now.

“I’m on a horse every day for four to five hours,” said Lukas, who’s usually first in line. “I open the gate for the track crew every morning. I ride a good horse, and I make everybody who works for me ride one.

“My wife (Laurie) rides out most days. She’s got a good saddle horse. I make sure my number one assistant, Bas (Sebastian Nichols) rides, too.”

The Hall of Fame trainer is unwavering in his stance.

“I want to be close to my horses’ training, because I think most of the responses from the exercise rider and the horse are immediate on the pull up after the workout or the exercise,” Lukas said.

“I don’t want that response 20 minutes later as they walk leisurely back to the barn. I want it right there. If I’m working a horse five-eighths, and I have some question about its condition, I want to see how hard it’s breathing myself, before it gets back to the barn.

“I’ve always been on a pony when my horses train, ever since I started. I’ve never trained from the ground. If my assistants don’t know how to ride, they have to take riding lessons, and they’ve got to learn how to ride. I insist on them being on horseback.”

Wesley Ward, a former jockey and the 1984 Eclipse Award winner as the nation’s leading apprentice rider, is a landlubber these days as a trainer, yet has achieved plaudits on the international stage.

Wesley Ward

“I don’t think there’s any advantage at all on horseback,” said Ward, who turns 51 on March 3. “Look at (the late) Charlie Whittingham. “He’s the most accomplished trainer in history, I think, and he wasn’t on a pony . . . Everybody’s different. It’s just a matter of style. I can see more from the grandstand when the horses work.

“I like to see the entire view, and on a pony, you’re kind of restricted to ground level, so you can’t really tell how fast or how slow or how good they’re going.

“I like to step back and observe the big picture when my horses work. I can check on them up close when they’re at the barn. But all trainers are different. Some like to be close to their horses and see each and every stride. I’ve tried it both ways, and I like it better from an overview.”

Two-time Triple Crown-winning trainer Bob Baffert, himself a former rider, employs the innovative Dick Tracy method: two-way radio from the ground to maintain contact with his workers on the track.

Bob Baffert

“I used to train on horseback,” said Baffert, who celebrated his 66th birthday on Jan. 13, “but you can’t really see the whole deal when you’re sitting on the track. From the grandstand, you can see the horses’ legs better and you can pick up more.

“On horseback, you can’t tell how fast a horse is really going until it gets right up to you. That’s why I switched. I have at least one assistant with a radio who’s on horseback, and I can contact him if someone on the track has a problem.”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

Breeders’ Cup 2018, issue 50 (PRINT)

$6.95

Pre Breeders’ Cup 2018, issue 50 (DOWNLOAD)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Print & Online Subscription

$24.95

Andrew Lerner - a young trainer on the up

By Ed Golden

Andrew Lerner looks like he just stepped off the pages of GQ.

At 29, six feet tall, 180 pounds and hazel eyes, he oozes subtle masculinity and innate innocence, bearing the attributes of an NFL tight end.

Picture Superman and Clark Kent or Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

But beneath that demure demeanor lies his true countenance, horse trainer, body and soul.

It was not a matter of if, but when it would happen.

“I created a couple of businesses that fortunately did well, and that put me in a position to buy some horses,” Lerner said. “I sent them to trainer Mike Pender with the caveat that I wanted to learn to train.

“I started a company with a friend of mine in 2012 and we did well; I sold half of it, not for a fortune, but for enough where I was able to buy a horse named Be a Lady and give it to Pender.

“That’s how it all began. She’s still racing.

“I told Mike I wanted to learn how to train, came out every morning at 4:30, shadowed his grooms and hot walkers for about a year and a half, then decided I wanted to learn how to ride, not at the track but somewhere else, just to get an idea of what the jocks and exercise riders were talking about when they got off a horse and told us how it went.

“I wanted to understand first-hand what they were explaining, more than just hearing their words. After that, it took me about six months to get my trainer’s license in March of last year.

“It was a small stable initially, just me, a groom and two horses. Now we’re up to about 22 head.”

Lerner came to Pender’s barn every morning, not with a chip on his shoulder but a thirst for knowledge.

Thus, Pender readily recognized that Lerner would triumph against the odds. His acuity was ever present.

“He won a race with the first horse we claimed together, and we were off and running,” said Pender, 52, a Los Angeles native whose major stakes winners in a career approaching 15 years include Jeranimo and Ultimate Eagle.

“When he told me he wanted to train, I asked why he would do such a crazy thing, and he was emphatic. He said he wanted to, and I knew how he felt because I had been in his shoes at one time.

“I told him he was going to fail more than he’d succeed and tried to talk him out of it, but he stood his ground. Even after I told him the only way to succeed was through hard work and spending a lot of money—some of it coming out of his own pocket when owners don’t pay and walk away leaving you high and dry with a $10,000 feed bill—he remained firm.

“He gave the right answers to all my questions, but most importantly, he showed up every morning. I’ve had a lot of guys walk through my doors saying they want to become trainers, and I feel a responsibility for them to achieve that goal, because it’s trainers who bring in new owners.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

Spring 2019, issue 51 (PRINT)

$6.95

Spring 2019, issue 51 (DOWNLOAD)

$3.99

Add to cart

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Print & Online Subscription

$24.95

Add to cart

Javier Jose Sierra - Invisible no more

By Ed Golden

Javier Jose Sierra has survived if not prospered for 45 years in a game he loves. Yet, he does not warrant a bio in any media guide.

He is racing’s Invisible Man.

The 66-year-old trainer has been sedulously plying his trade despite lack of recognition, ego be damned.

A native of El Paso, Sierra stands on a foundation adorned with pillars of self-confidence, gained in no small part from a proper upbringing in a family of 12 children, and tours early on with legendary trainers D. Wayne Lukas and J.J. Pletcher, father of Todd Pletcher.

Sierra grew up in Juarez where he played soccer as a kid. At 14 he aspired to be a jockey at Sunland Park in New Mexico, but his father, Cirilo, a native of Mexico, made education a priority. Javier aborted racing, went to school at the University of Texas El Paso (UTEP) and graduated with a degree in electrical engineering. Eventually, he earned an MBA while still working full time.

“I was doing well as an engineer,” Sierra said. “I worked my way up to vice president at an aerospace company.”

The appeal of the turf, however, proved an alluring temptress. Duly smitten, Sierra ultimately came to California in 1976.

“As soon as I graduated from college, I loved racing so much, I bought a couple horses,” he said. “I was doing both jobs at the same time, training horses and working in the aerospace industry.”

Most of Javier’s family were involved in racing. “All my brothers worked in racing in different positions, grooms, hot walkers, exercise riders, thanks to my father, who was a trainer.

“While in college, I worked three summers for Lukas when he trained quarter horses in New Mexico, and with J.J. Pletcher one year at Sunland Park. I remember Todd being there. He was probably five years old.

“I learned a lot from both men, especially Pletcher. I was impressed with the quality of horses he brought in from back east. One was a son of Bold Ruler named First Edition. J.J.’s training regimen was amazing, completely unlike everyone else there at the time.

“Gerald Bloss was another big trainer from New York who was in New Mexico in the ‘60s. He was like Baffert is now. He had big owners, like DuPont, and used different techniques from those of the cowboys. We learned a lot from those guys.”

Bloss trained the great Gallant Man in the first part of his two-year-old season before he was transferred to New York with John Nerud.

Gallant Man, along with Bold Ruler and Round Table, in 1957 comprised arguably the greatest crop of three-year-olds ever. Gallant Man finished second by a nose to Iron Liege and Bill Hartack in that year’s Run for the Roses when Bill Shoemaker, aboard Gallant Man, misjudged the finish line and stood up in the stirrups in the shadow of the wire.

Gallant Man went on to win the Belmont Stakes and at age 34, became the longest living horse to win a Triple Crown race. He died on Sept. 7, 1988. Count Fleet was the previous record holder, having died on Nov. 30, 1987 at the age of 33 years, eight months.

“My older brother, Cirilo Jr., was an assistant trainer for Jake Casio who conditioned quarter horses in New Mexico for many years,” Sierra continued, “but when Jake died, I asked my brother to help me train at Santa Anita. Ten years ago, he retired and I took over training full time, giving up my job in aerospace.”

All these years later, he is a mainstay in the Golden State, making Santa Anita his headquarters save for tours at Del Mar when the seaside track is open. He lives 17 miles from Santa Anita in La Crescenta, with his wife, Dulce. He has never raced on the East Coast.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

Breeders’ Cup 2018, issue 50 (PRINT)

$6.95

Pre Breeders’ Cup 2018, issue 50 (DOWNLOAD)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Print & Online Subscription

$24.95

Val Brinkerhoff - the former jockey turned trainer

By Ed Golden

The Santa Anita stable notes for April 14th (as written by Ed Golden) succinctly summarize that Val Brinkerhoff is one of the faceless trainers who drives the game.

He might be light years from being in a league with the Bafferts, Browns, and Pletchers but pound for pound, the 62-year-old Brinkerhoff has one of the most industrious operations in the land, flying beneath the radar while gaining respect from peers and bettors alike.

He’s an angular version of John Wayne, cowboy hat and all, but without the girth and swagger, Brinkerhoff is a hands-on horseman from dawn till dusk.

He is a former jockey who gallops his own horses, be they at Santa Anita, Del Mar, Turf Paradise in Arizona, or his training center in St. George, Utah, where he breaks babies and legs up older horses that have been turned out.

In short, Val Brinkerhoff is a man’s man, pilgrim.

It all began when he was 14 in a dot on the map called Fillmore, Utah, current population circa 2,500.

Named for the 13th President of the United States, Millard Fillmore, it was the capital of Utah from 1851 to 1856. The original Utah Territorial Statehouse building still stands in the central part of the state, 148 miles south of Salt Lake City and 162 miles north of St. George.

But enough of history.

“My dad trained about 30 horses when we lived in Fillmore,” said Brinkerhoff, a third-generation horseman. “I would ride a pony up and down a dirt road outside our house every day, and that’s how I learned to gallop horses.

“There was no veterinarian in Fillmore, so you had to learn how to be a vet on your own, on top of everything else, because it was 300 miles round trip to a vet. So, if something was wrong, you had to figure it out for yourself without having to run to Salt Lake and back every five minutes.

“I was 5’ 10’’ and weighed 118 pounds and rode at the smaller venues, mainly in Utah but also Montana, where I was leading rider, and Wyoming and California (Fairplex Park in Pomona). I’ll never forget the day my dad took me to Pomona. I walked in the jocks’ room and immediately became aware of how tall I was.

“While in California, Bill Shoemaker gave me one of his whips, which I cherished. I rode many winners with it. Towards the end of my father’s life, my son, Ryan, asked him if he had any regrets. He said he had one.”

His father said, “I should have taken Val to the big tracks in California and given him the chance to make it there. He had the desire and the talent.”

Brinkerhoff also rode in Utah at outposts with names that sound contrived, like Beaver, Richfield, Marysvale, Kanab, Parowan, Ferron, Payson, and Panguitch.

“But ultimately,” he said, “I couldn’t make the weight. I was already skinny and at 5-10 and 118 pounds, didn’t have an ounce to lose.

TO READ MORE --

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

August - October 2018, issue 49 (PRINT)

$5.95

August - October 2018, issue 49 (DOWNLOAD)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Print & Online Subscription

$24.95

Standing in the wings - Assistant Trainers

By Ed Golden

The term “second banana” originated in the burlesque era, which enjoyed its heyday from the 1840s to the 1940s.

There was an extremely popular comedy skit where the main comic was given a banana after delivering the punch line to a particularly funny joke. The skit and joke were so widely known that the term “top banana” was coined to refer to anyone in the top position of an organization.

The term “second banana,” referring to someone at a pejorative plateau, had a similar origin from the same skit. There would have been no Martin without Lewis, no Abbott without Costello, and no Laurel without Hardy.

Racing has its own version of second bananas, only they’re not in it for the yuks. They’re called assistants, and it’s a serious business.

Most of the laughs come in the winner’s circle, and if not outright guffaws, there at least have been miles of smiles for Hall of Fame trainer Jerry Hollendorfer and assistant Dan Ward, who spent 22 years with the late Bobby Frankel before joining Hollendorfer in 2007.

While clandestinely harboring caring emotions in their souls, on the surface, Frankel did not suffer fools well, nor does Hollendorfer. A cynic has said Ward should have been eligible for combat pay during those tours.

But he endures, currently with one of the largest and most successful barns in the nation, with 50 head at Santa Anita alone. Hollendorfer hasn’t won more than 7,400 races being lucky. It is a labor of love through dedication and scrutinization to the nth degree, leaving little or nothing to chance.

A typical day for the 71-year-old Hollendorfer and the 59-year-old Ward would challenge the workload of executives at any major corporate level. Two-hour lunches and coffee breaks are not on their priority list.

“I get to the track before three in the morning,” Ward said, “because we starting jogging horses at 3:30. It takes about a half-hour until we get every horse outside, check their legs, jog them up and down the road, and if we see something that will change our routine--the horse doesn’t look like it’s jogging right or if it’s got a hot foot--we’ll adjust the schedule.

“We won’t send a horse to the track without seeing it jog. We’ll watch all the horses breeze, and if something unexpected happens that we have to deal with, we diagnose it and take care of it. Meanwhile, we’re also going over entries and the condition book, making travel arrangements and staying current on out-of-town stakes and nominations.

“Each time a new condition book comes out, I go over it with Jerry, we agree on which races to run in, and then go out and try and find riders.

“I’ll ask him what claiming price we should run a horse for, but with big stakes horses, the owners have the final say. Jerry and I usually agree on the overnight races, but in some big stakes, it might take more time deciding which horses run in what races. All this consumes most of the day, plus doing the time sheets and the payroll.”

It’s a full plate even with a shared workload, but Ward is considering flying solo should a favorable chance come his way.

“I’m hoping to go on my own,” he said. “Right now, I’m in a very good position, but if the right opportunity comes along, or if Jerry one day decides not to train anymore, I would be qualified to take over. In the future, however, I definitely hope to train on my own.”

Despite his workaholic demeanor, Ward has found time recently to enjoy a slice of life in the domestic domain.

“I was married for a year on March 6 and it’s been the best time,” he said. “My wife (Carol) already had two kids, and now they’re our kids, and it’s really great.”

Ward is a worldly man with diversity of thought, traits Hollendorfer sought when he brought him on board.

“In my barn, I often give the reins to my assistants,” Hollendorfer said. “I like them to make decisions, so when I hired Dan Ward I told him that I wasn’t looking for a ‘yes man’ but for somebody who would state his opinion, and if he felt strongly about it, to stand his ground.

“I make the final decisions, but I want a person who is not afraid to make decisions and lets me know what’s going on when I’m not there. There’s not a successful trainer I know of who doesn’t fully have good support back at his barn, and that’s where I’m coming from.

“It’s not only Dan who makes important contributions, it’s (assistants) John Chatlos at Los Alamitos and Juan Arriaga and (wife) Janet Hollendorfer in Northern California.

“Your supporting cast of assistant trainers has to be solid, too,” said Hollendorfer, who had a trio of three-year-olds hoping to prove they were Triple Crown worthy at press time: Choo Choo, a son of English Channel owned and bred by Calumet Farm; Lecomte winner Instilled Regard; and San Vicente winner Kanthaka.

“If horses are good enough to go (on the Triple Crown trail), you go,” Ward said. “If you miss it, you concentrate on a late-season campaign. It worked well for Shared Belief and Battle of Midway.” Shared Belief, champion two-year-old male of 2013, won 10 of 12 career starts but missed the 2014 Kentucky Derby due to an abscess in his right front foot. Given the necessary time off, he recovered and won the Pacific Classic later that year, and in 2015, the Santa Anita Handicap.

Battle of Midway outran his odds of 40-1 finishing third in the 2017 Kentucky Derby and won the Breeders’ Cup Dirt Mile last November.

Ron McAnally, in the homestretch of a Hall of Fame career that has reaped a treasure trove of icons led by two-time Horse of the Year John Henry, is down to a dozen runners at age 85, none poised to join Bayakoa, Paseana, Northern Spur, and Tight Spot on the trainer’s list of champions. As McAnally says, “I have outlived all my owners,” save for his wife, Deborah, and a handful of others.

Still, maiden or lowly claimer, Thoroughbreds deserve the best of care, which any dedicated trainer readily provides, cost be damned. His glorious past well behind him, trouper that he is, McAnally remains a regular at Santa Anita, although leaving all the heavy lifting to longtime assistant Dan Landers.

Landers was born in a racing trunk, to paraphrase an old show business lexicon. His late father, Dale, rode at Santa Anita the first day it opened, on Christmas Day 1934, and won the second race on a horse named Let Her Play. Landers still has a chart of the race.

“Even if I weren’t here for a few weeks, Dan would know what to do because he’s been with us a long time,” McAnally said. “Dan really works hard, and although he’s got three or four grooms, if they don’t perform their duties as they should, he finds someone else.

“That’s the type of guy he is. He wants things done perfectly--the barn is always clean--and that’s what you look for in an assistant, someone who can take your place when you’re not there, and he’s there.

TO READ MORE --

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

August - October 2018, issue 49 (PRINT)

$5.95

August - October 2018, issue 49 (DOWNLOAD)

$3.99

Why not subscribe?

Don't miss out and subscribe to receive the next four issues!

Print & Online Subscription

$24.95

Career Makers - The Role of Jockeys’ Agent

By Ed Golden

Manager, mastermind, guru, agent, call him what you will, Colonel Tom Parker was the man who made Elvis Presley.

The King of Rock and Roll’s talent was only exceeded by his raw sex appeal, and Parker, self-proclaimed military officer or not, saw to it that the world would march en masse to a cadence called by Presley’s signature tones.

Elvis died more than four decades ago, but not before he and Parker reached the apex in gold and glory, still yielding riches of infinite proportions all these years later.

In racing, it’s not clothes that make the man; in part it is the agent directing the jockey. Agent and jockey provide a service to trainers, a salesman offering a product.

An agent in this instance is best described as a person empowered to transact business for a jockey. On any given morning at any given track, condition book in hand, there they are, Monty Hall wannabes, ready to make a deal.

A standard arrangement calls for an agent to be paid 25 percent of a jockey’s earnings, but that percentage could vary. If the rider’s services are in great demand, he could pay the agent a smaller percentage. Or, if the agent possesses the persuasive prowess of a Colonel Parker, he could warrant the higher percentage. It’s Economics 101.

Back in the day, agents were not prominent, if in evidence at all. Major stables employed contract riders and in order to ride for an outside trainer, the jockey had to receive permission from his contract stable to do so.

Now, the vast majority of riders have an agent, although jocks on a restricted budget with limited mounts have been known to represent themselves.

Agents wear many hats, including those falling under the Three P’s: politician, psychiatrist, and pacifist, and they can be a boon to racing departments.

“In my career around the country at tracks on both coasts, I’ve worked with agents who mostly helped the racing office,” said Rick Hammerle, Santa Anita’s vice president of racing as well as racing secretary. “We’re both trying to accomplish the same thing: get horses into races. Working with agents and sharing information about trainers’ intentions can help us achieve our goal.”

Even though it’s his first tour as an agent, Mike Lakow has racing’s paradigm of Tom Brady in jockey Javier Castellano, a 40-year-old Venezuelan at the zenith of his career. The reigning four-time Eclipse Award winner, a world class rider be it at Dubai or Churchill Downs, was inducted into racing’s Hall of Fame in 2017.

Still, for an agent, the pressure is always on.

Although he never trained, the 60-year-old Lakow (pronounced LAKE-ow) otherwise has an extensive background enabling him to understand ramifications that simmer just below racing’s surface.

“When I was working as general manager at Hill ‘n’ Dale (a major breeding farm in Kentucky),” he said, “I owned a quarter of one horse, and believe me, it’s a tough deal, so I respect all the owners, as well as trainers.”

Lakow, now based on the East Coast, was racing director at Santa Anita before Castellano hired him in August of 2016. Lakow also was racing secretary for the New York Racing Association (NYRA) from 1993 to 2005, served as a racing official in Florida and Dubai, and was hands-on with horsemen regularly at Santa Anita’s Clockers’ Corner during his sojourn at the historic Southern California track.

“I’m incredibly fortunate to represent Javier,” Lakow said, “because he’s a professional who’s liked by everybody. We have no issues as far as not being able to ride for one trainer or one owner. He’s won four Eclipses, done it all, and now we’re trying to focus on riding the top horses.”

Stress and pressure are standard fare in the workforce, whether you’re Donald Trump unceasingly enduring “fake news” attacks 24/7 or a McDonald’s minimum wage burger slinger serving up $2.50 McPicks. It’s all relative.

That includes Lakow, although he is averse to pointing it out, lest he might be looked upon as a malcontent, what with two chickens in the pot.

“People who see all the money we’re making might wonder how being agent for a top jockey could be stressful, but it is,” Lakow said. “I’ve been in administrative positions in racing for many years, with NYRA and at Santa Anita, but if you happen to make a mistake here and there, you move on.

“It affects the company, but it doesn’t affect an individual. If I happen to make a mistake with Javier, it affects him.

“It’s impossible to keep everybody happy. Any agent will tell you that. Fortunately, Javier is level-headed, so I’m in a good position. That’s not the case with some other jockeys, from what I’ve heard. I respect Javier and Javier respects me, but like I’ve said, it’s impossible to keep everybody happy.

“You try to do the right thing. I respect all the horsemen who give us calls, because it’s a tough game for trainers. Horses will fool you, so I understand the stress trainers and owners face. I don’t look at this as a one-shot relationship.

Tom Knust

“Luckily, I have the respect of horsemen because of my work in New York and California. When I started with Javier, horsemen gave me the benefit of the doubt. I was a bit green and I think other agents probably thought, ‘Look at this guy. He starts a job and has a top rider,’ but I’m lucky because I didn’t burn any bridges. I get along with most people and treat everybody with respect. That’s what’s made it so much easier for me.

“In the long run, honesty is the best policy, and I’m always honest. It hurts sometimes, but in the long run, I think it helps.”

Another agent who has been on both sides of the wall is Tom Knust, former racing secretary at Santa Anita and Del Mar, now booking mounts for two-time Kentucky Derby-winning jockey Mario Gutierrez.

“One thing I learned quickly as an agent is that if you have a good rider, it makes things pretty easy, and if you don’t, it’s very, very difficult,” Knust said. “That’s the key, whether you’ve had experience in the racing office or you’ve just come in off the street.

“If you give a call, you want to honor it, although situations develop where you’re in a bind and ask a trainer if he can help you out, but if he doesn’t, you’ve got to keep your word and ride his horse.”

An additional plus comes from riding regularly for a winning trainer, in the case of Gutierrez, that being Doug O’Neill, who saddled I’ll Have Another and Nyquist to capture the Kentucky Derby for principal owner J. Paul Reddam in 2012 and 2016.

“It’s absolutely an advantage, 100 percent, if you have a go-to stable that wins a lot of races, like O’Neill,” Knust said.

As a female, Patty Sterling is in the minority among agents, but with her extensive familial background in racing, she is looked upon as one of the boys.

Her late father, Larry, trained 1978 Santa Anita Handicap winner Vigors and is the father of jockey Larry Sterling Jr. Patty’s uncle, Terry Gilligan, rode and trained, and his brother, also Larry, made his bones as a rider, too. Now 80, he is the quick official at Santa Anita and Del Mar.

“It’s probably a lot easier for a woman in this business than it used to be,” said Patty, 54, a former clocker. “I don’t see that as a problem.

“Being an agent is almost parallel to training horses; it’s very similar. Right now, it seems owners pick the jockeys more so than they ever did before, when trainers were deciding who to ride.”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

Spring 2018, issue 47 (PRINT)

$6.95

Spring 2018, issue 47 (DOWNLOAD)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Print & Online Subscription

$24.95

The Art of Clocking Horses

Published in North American Trainer, Winter 2017 issue.

Time, an old racetrack axiom holds, only counts in prison.

But that ain’t necessarily so to horse players and horsemen worldwide who depend diligently on mathematical mavens called clockers to provide thorough, accurate, and prompt figures that might help cash a bet or win a race.

Clockers, succinctly described as people who time workouts, ply their trade at tracks from Aqueduct to Zia Park, zeroing in on Thoroughbreds and their exercises from before sunup until the track closes for training, a span of some five hours.

There are private clockers, too, whose primary interest focuses on padding their wallets or making their valued information available to the public for the right price.

They all watch like hawks, displaying the close-up intensity of a movie directed by Sergio Leone, often adding a comment such as “breezing” or “handily,” the latter being the most accomplished workout.

Each track later in the morning sends its works to Equibase, which publishes distances and times of said workouts for all to see, a regimen that has been ongoing for decades...

![KIp HannanBy Ed GoldenIn an age of “Races Without Faces,” Edward Kip Hannan is a renaissance man.Not to be confused with an anarchist bent on destroying history’s truths, Hannan is an archivist, with an ethos dedicated to preserving timeless treasures and ensconcing them in pantheons for future generations.With the artistic and obdurate passion of a Michelangelo, when Hollywood Park closed forever on Dec. 22, 2013, like a man possessed with an oblation, Hannan knew there was “gold in them thar hills” and dug in like he was assaulting the Sistine Chapel.Far from a fool and capitalizing on today’s applied sciences, Hannan has successfully transitioned through more than four decades, surviving—yea, overcoming—a concern once epitomized by Albert Einstein who said: “I fear the day that technology will surpass our human interaction. The world will have a generation of idiots.”Hannan made it his mission to rescue archives from the Inglewood, Calif. track that opened 75 years earlier on June 10, 1938. The Hollywood Turf Club was formed under the chairmanship of Jack L. Warner of the Warner Brothers film corporation.Among the 600 original shareholders were many stars, directors and producers of yesteryear from movieland’s mainstream, including Al Jolson, Raoul Walsh, Joan Blondell, Ronald Colman, Walt Disney, Bing Crosby, Sam Goldwyn, Darryl Zanuck, George Jessel, Ralph Bellamy, Hal Wallis, Wallace Beery, Irene Dunne and Mervyn LeRoy.They pale, however, compared to the equine stalwarts that raced at Hollywood Park, which include 22 that were Horse of the Year: Seabiscuit (1938), Challedon (1940), Busher (1945), Citation (1951), Swaps (1956), Round Table (1957), Fort Marcy (1970), Ack Ack (1971), Seattle Slew (1977), Affirmed (1979), Spectacular Bid (1980), John Henry (1981 and 1984), Ferdinand (1987), Sunday Silence (1989), Criminal Type (1990), A.P. Indy (1992), Cigar (1995), Skip Away (1998), Tiznow (2000), Point Given (2001), Ghostzapper (2004) and Zenyatta (2010).Hannan obviously had his hands full, but thrust ahead undeterred as he soldiered on to digitize Hollywood Park’s entire film/video history of nearly 4,000 stakes races for eventual public access.It seemed a mission mandated by a higher power.Hannan, who turns 57 on Jan. 29, was born in Phoenix, Ariz., where his mother and father had come from Brooklyn. Moving to California when he was just two, they lived on the Arcadia/Monrovia border within a couple miles of storied Santa Anita, and left in 1972 for nearby Temple City where Kip has lived ever since.In 1979, at the tender age of 15, he began working as a marketing aide at Santa Anita under the aegis of worldly racing guru Alan Balch and his fastidious publicity sidekick, Jane Goldstein.He was the last employee at Hollywood Park in order to organize archives for digitization and eventual transfer to the UCLA Library, where he began working in late 2014 as videographer and editor. He is still employed there, maintaining the integrity of Hollywood Park film, video, photo and book archives.Hannan sums up his career in one word: “Fascinating.”“I had already started collecting music at age 11, in 1975,” Hannan said, “and probably because of this, I associate many life events with the music of the time. I’m sure many people can relate.“It was at Santa Anita where and when I first met Lou Villasenor, who was already working there and would go on to become a staple of its TV broadcast team—a job he held for nearly 35 years before his death in 2018.“Lou became one of my best friends and eventually was the one who brought me to Hollywood Park where I was hired to work in its television department in 1986.”As marketing aides, their tasks were menial and labor intensive, such as removing duplicates from mailing lists, organizing contest entry cards filled out by fans, and other simple office-related duties. After a few years, Hannan was promoted to supervisor.At Santa Anita in 1982, Hannan met another new hire who became an instant best friend: Kurt Hoover, current TVG anchor whose relaxed and ingratiating on-camera presence is the stuff of network standards. He also is a devoted and skilled handicapper and a successful horse owner.“We hit it off immediately,” Hannan says.A couple years later, Hannan left Santa Anita briefly to study television production at Pasadena City College, while also finding time to work at Moby Disc Records in town.“I had always been a movie buff, with the original 1933 ‘King Kong’ my inspiration, along with ‘One Million Years B.C., and not just because of Fay Wray and Raquel Welch—although I had crushes on both. It was the dinosaurs and the stop-motion filmmaking and special effects.“I wanted to get into film somehow but couldn’t afford USC, so the gateway was video/television production, first in high school and then at Pasadena City College.“It was around this time, summer of 1985, that Santa Anita contacted me out of the blue,” he said. “Knowing I had radio operation training in college, they told me of a radio station in the planning stages that would be an on-site source for racing fans and handicappers broadcasting information throughout the day.“Nearly doubling my hourly wage from the record store, I jumped at the chance. It was designed and organized by the same company that created the low-power AM radio station that can be picked up near the LAX Airport for flight information; and soon, KWIN Radio AM was created.“I was the operator/engineer with countless marketing people and handicappers available for on-air hosts and guests. It was at this time I met Mike Willman, the ‘roving reporter’ and program manager of sorts, who gathered interviews on his cassette recorder for us to air.“On April 23, 1986, Villasenor took me to Hollywood Park where he was program director and graphics operator in its TV department.“I was fortunate to be there and was in the right place at the right time. They were short of cameramen that day, and word came from Hollywood Park President Marje Everett that many of her personal friends would be attending, including popular celebrities of music, film, television and politics.“The TV department was to capture ‘Opening Day Greetings’ from them on their arrival. The TV director asked if I could handle the professional portable camera, portable tape deck and tripod. I said yes, gathered up everything, and headed to the Gold Cup Room, avoiding crowded elevators with all that gear.“It was then I realized my career was moving up, for at that moment, not three steps behind me on the escalator were Elizabeth Taylor and Michael Jackson. As we continued to climb, all I could think of was getting to a phone to tell my folks how my first day went, before it had even started!“There is one particular snapshot taken in the Gold Cup Room that I cherish. I’m not in the photo but was about six feet ahead of them, walking with my gear like I was on top of the world at age 22.“I did get Michael Jackson’s autograph later, as miraculously he only had one bodyguard with him that day. At the time, there was not a bigger pop music star on the planet, and it was surreal to see him right before me.“Even though they both declined to appear on camera for a greeting, it was Elizabeth Taylor who got to me. As I set up my camera gear not 25 feet from where she was sitting (and momentarily alone), she glanced up from the table and looked directly at me with this big smile.“I literally melted! As I continued to fumble getting the camera onto the tripod, I kept thinking, ‘Dear God, those eyes!’ and I was ready to sign on for husband number seven, as suddenly it had all made sense to me.“That was my first day as a TV professional that I’ll never forget.”Hannan also has noteworthy literary credits.“I was fortunate to be mentioned in the ‘thank you’ section of Laura Hillenbrand’s best-selling book, Seabiscuit, for simply providing her with basic Seabiscuit footage from Hollywood Park,” he said. “I sure wish I could have sent her all the eventual work I did years later, after I had restored all of Seabiscuit’s existing race films, including some four-minute vignettes on the 1938 Gold Cup, the famous match race with War Admiral and the 1940 Santa Anita Handicap, before her book was published.“Through a connection via Charlotte Farmer—a fan who had rescued the great horse Noor’s remains from land repurposing and moved them across the country to be reinterred at Old Friends in Kentucky—I contributed photos to Milton C. Toby’s book, Noor-A Champion Thoroughbred’s Journey from California to Kentucky.“These included the cover photo of Noor working out with Johnny Longden up, which came from a negative that had probably been unprocessed and unseen for 62 years!“A few years ago, I was asked to contribute to a book by photographer Michele Asselin, who had been commissioned to photograph and document the closing of Hollywood Park and its people during late 2013 and early 2014. It resulted in a coffee table photobook entitled Clubhouse Turn—The Twilight of Hollywood Park Race Track, which was published in March 2020.“With Roberta Weiser, we wrote a detailed Hollywood Park ‘timeline’ for the end of the book, to provide a sense of the track’s history, which was only being represented in the book by photos of its final months.“Without Roberta, the rescue, work and maintenance of the entire Hollywood Park archive would not have happened, and more importantly would not exist to this day.”Displaying his passion and knowledge of music globally from note to note, Hannan also edited a full-length DVD version of Laffit Pincay Jr.’s retirement ceremony at Hollywood Park in July 2003.“I added music from the Mascagni opera, Cavalleria Rusticana, during Laffit’s farewell speech,” Hannan said. “If you think of the music soundtracks to either the opening scene of Raging Bull (with the boxer in the ring by himself, feinting blows in slow motion) or the final scene on the steps in Godfather III, it might come to you.“If you don’t get a lump in your throat and your eyes don’t water when Laffit says, ‘I still have that fire inside me that I cannot put out . . .’ before he continues with his tearful and thoughtful farewell moment, hugging his very young son, his grown children and his mother, then we might need to check your pulse.”Another of Hannan’s highlights was the creation of a “quadruple whammy Living Legends” music video in 2005, honoring four recently retired legendary jockeys in the Hollywood Winners’ Circle: Pincay, Chris McCarron, Eddie Delahoussaye and Julie Krone. The piece was done with no narration, accompanied only by visuals and Electric Light Orchestra’s powerful instrumental, “Fire on High.”“As a music collector, researcher, cataloger, historian and fan, it’s not much of a stretch to see how I was able to latch on to the Hollywood Park archive and become its archivist. I treated it the same as my music collection, gathered it and organized it . . . I knew I had an audience that wanted history to remain alive, so I kept it going the next five or six years.“I restored clips of Seabiscuit winning the first Gold Cup in 1938 . . . found a color film reel with footage of Citation from 1951—probably not seen by anyone in 60 years—and had that professionally restored along with the earliest color film found of Hollywood Park from 1945. The cool stuff just kept turning up . . . Native Diver’s 1967 farewell parade after his third consecutive Gold Cup victory, Cougar II’s 1971 win over Fort Marcy in the Hollywood Turf Invitational, and the 1978 Swaps Stakes with J.O. Tobin beating Triple Crown winner Seattle Slew in front of 68,000 fans.”Hannan’s favorite race is Lava Man winning a third consecutive Gold Cup in 2007, tying Native Diver’s mark. “I stood up and screamed all the way down the stretch at the TV screen in my little editing room,” he said. “What a race and what a finish! Thank you, Lava Man and Corey Nakatani.”But had the fates allowed, his choice would have been the 2010 Breeders’ Cup Classic in which Zenyatta, the remarkable stretch-running mare, suffered her only defeat after 19 straight dramatic come-from-behind victories, losing by a head to Blame ridden by the late Garrett Gomez.“’Zenyatta: Queen of Racing,’ was a career highlight for me and the best I’ve ever done,” said Hannan, who enlisted Jay Hovdey to help script it. “Such a beautiful horse and fan favorite. Her wonderful story was easy to tell, but once again I had to tell it right for her legion of fans.”The Zenyatta story was buoyed, thanks to music by The Police and Sting, and by Hannan’s brother Chris, who composed all the original music.Added Hannan: “I still feel Zenyatta gave her greatest performance in defeat, making up 18 lengths at one point against the best boys in the world at her age [six], at night with lights on [a first for her] and on an unfamiliar [Churchill Downs] surface.“That stretch run was another screamer for me, but to come up short by so little was a heartbreaker . . . If she gets up and beats Blame, it’s the greatest race of all time. That’s my two cents; sorry, Lava Man.”Hannan’s favorite tale is about horse owner and music legend Burt Bacharach who was at Hollywood in 1996 but on this particular day had a horse running at Keeneland and wanted to see the race.Hannan picks it up from there. “Our TV department scrambled to downlink a satellite feed from Keeneland to do it,” he recalled. “I put the track’s feed on the monitor and ran into another room and popped in a tape to record the race, just in case.“Burt came in a few minutes later. I welcomed ‘Mr. Bacharach’ and he said, ‘Please call me Burt,’ I said ‘OK’ and escorted him down the hall to a room where he could watch his race. As I was stepping out, I said, ‘Good luck with your horse” to which he quickly replied, ‘No, you don’t have to go. Sit down and help me cheer on my horse.’“As I sat there, I couldn’t stop thinking about this musical genius sitting right next to me, dressed casually as always, in a tracksuit with a sweater around his neck—one of the most beloved and successful songwriters of all time, sharing horse racing chit chat with me.“At first I held back from telling him I was a great fan and collector of music, how I used to write down the Top 40 every Sunday morning while listening to Casey Kasem on the radio, how so many of those classic songs were written by him and his lyricist, Hal David, and how my dad was also a music collector . . . I patiently waited to see how the race went first.“The race went off, and we were both yelling down the stretch as his horse pulled away and won easily. We both cheered, and as I turned to Burt, he had his hand raised ready to receive a high five. I graciously obliged, of course. ‘Holy cow,’ I thought. ‘I just high-fived Burt Bacharach!’“I told him I had taped the race and could make him VHS copies later; he was very happy to hear that. It was then that I informed him I was a music nut and respected his amazing body of work. We talked music for a few minutes to the point that he realized I knew my stuff, and he said he would have his secretary send me a CD box set of his songs, although I never thought it would happen.“Two days later at home on a Tuesday, my off-day, there was a medium-sized white envelope on my doormat with a return address on it but no name. It didn’t hit me until I opened it.“Inside was a four-CD box set, a publishing promo unavailable to the public containing all of Burt Bacharach’s hit songs as recorded by the performers who made them hits. It included a small, handwritten note with ‘Burt Bacharach’ printed as a letterhead at the top. “To Kip—hope you enjoy—thanks again for all your help—appreciate!”—Burt Bacharach.“Boy, I was impressed. What a kind gesture from a really, really nice guy and one of my heroes. My favorite Hollywood celebrity story by far.”After Hollywood Park closed, Hannan stayed for an additional nine months to move and organize the archive and prepare it for digitization—a laborious and emotional task in its own right—as the track was being demolished around him. His final day came on Sept. 30, 2014.“I had arranged for UCLA to send out two huge trucks that day for transporting much of the archive directly to its special collections’ library, while much of the rest would be kept and staged for the future stakes races’ digitization project,” Hannan said.“My time at Hollywood Park was done. Within two months, however, I was hired by the UCLA Library, after I had suggested they may need a curator for the collection they were just gifted. It worked out nicely, and I’m currently still employed there as a videographer.“The digitization project is finally coming to a conclusion, with well over 3,000 stakes races from the track’s history, beginning in 1938 through the final 2013 season. A computer database for the files’ metadata of statistics and for future cross-referencing is another ongoing project nearing completion.”As to his unique middle name of Kip, it’s a grand story in its own right. Hannan explains:“My maternal grandfather, Domenick Bertone—a man unfortunately I never got to meet as he passed away at 54, a year and a half before I was born—worked for Western Union and then Associated Press.“He could type 125 words a minute and became a linotype machine operator for the AP in New York. He was one of the first people on the east coast to receive news that Pearl Harbor had been attacked and couldn’t believe what he had to type out for the country to wake up and read.“Anyhow, I believe the story goes that he used to wear these round, wire-rimmed glasses, much like that of journalist, poet and novelist Rudyard Kipling, of Gunga Din and The Jungle Book fame.“Eventually, instead of Domenick or Dom, his coworkers nicknamed him ‘Kip,’ short for Kipling, because of his wire-rimmed glasses; and the nickname stuck.“So, to this day I refer to him as my Grandpa Kip. As for me, my mom decided to pass on her father’s nickname to her first son as my middle name, even though she had to fight for it at my baptismal because the priest said it wasn’t a saint’s name.“She begged to differ and eventually won, with the threat of going to another church as the deciding factor. As a baby, I was known as ‘Eddie Kip,’ utilizing both my first name and the name of my father, Edward (and his father) and my grandfather’s nickname.“As time passed, the ‘Eddie’ fell off, and I became ‘Kippy’ to everyone. Eventually, at the age of seven, I put my foot down and demanded to be called simply Kip.“However, I do use my full name for my signature and production credits. So, perhaps it’s all from Rudyard Kipling. I can’t know that for sure, but it might explain why, as a toddler, I was such a fan when Disney’s The Jungle Book movie came around in the late ‘60s.”Through the years, Hannan’s sobriquet has remained transfixed and true, adhering to these profound words of Henry David Thoreau: “Let us make distinctions; call things by the right names.”Edward Kip Hannan: fascinating, for sure.-30-](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/517636f8e4b0cb4f8c8697ba/1603533823467-N4HZPMR6FMS4CP2OH971/113110709041_Hollywood_Gold_Cup_Day_Scene.JPG)