How girths have been scientifically proven to have an impact on performance

By Dr. Russell Mackechnie-Guire

Groundbreaking research has revealed the effect girths can have on the locomotion of the galloping racehorse.

Generally, whenever the subject of tack and equipment is discussed, the saddle is always the first, and possibly even the only, consideration. Recent scientific studies have revealed interesting findings relating to girth design and its association with gallop kinematics (movement). These findings could bring significant benefits for trainers—in terms of performance and equine health.

It seems the girth has the potential to be more influential and important than ever been imagined. Indeed, the girth’s impact on equine locomotion has been reported to be so great that authors of a study suggest the girth and its fit should be considered by a veterinarian when evaluating a horse for poor performance.

Thanks to advances in technology, we have enhanced our understanding of the physiological and biomechanical demands placed on the horse. This evidence-based knowledge is leading to progress in the development of race and exercise tack, allowing trainers to optimise benefits brought about by the design and fit of saddles and girths—benefits which have been quantified using scientifically robust principles and state-of-the-art measuring systems.

Pressure matters

The association between saddle pressures and back discomfort is a topical area within the equine literature. Studies have reported that a mean saddle pressure of more than 13kPa, or peak pressure of more than 35kPa, has the potential to cause ischemia—compression leading to soft tissue and follicle damage. This can result in the appearance of white hairs, muscle atrophy and skin ulcerations, with the potential to induce discomfort.

It has always been assumed that girth pressures are at their highest on the midline of the horse’s trunk, at the horse’s sternum (breastbone) where the girth passes over the bone. In a study investigating girth design on sport horse performance, researchers identified repeatable high pressures beneath the girth, but these pressures were actually located behind the elbow, not on the sternum. This also seems logical, given it is the location where girth galls and girth pain may appear.

Adapting technology previously used in saddle-based research, using a pressure mat with 256 individual pressure sensor cells, researchers were able to quantify the precise levels and exact location of actual pressures beneath the girth. For the first time, they were able to demonstrate how the pressure distribution changes during locomotion and show that the pressure peaks are directly associated with the timings of the gait.

Limb kinematics were quantified using a two-dimensional motion capture system. The combination of pressure mapping and gait analysis demonstrated that a girth designed to alleviate pressure, particularly in the region behind the elbow, resulted in an improvement in equine locomotion and the horse’s movement symmetry.

Two-dimensional motion capture is used to quantify improvements in gait.]

Speed increases pressure

The groundbreaking findings from the sport horse study sparked further investigation into racing thoroughbreds. It is accepted that high speeds are associated with higher pressures under the saddle and, applying the same principles to a girth, it was speculated that girth pressures may increase with an increase of speed.

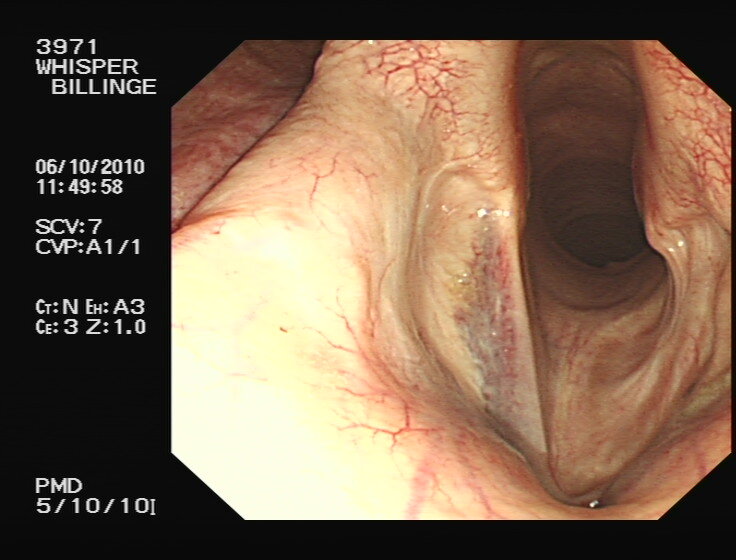

In a recent experiment, researchers quantified girth pressures in a group of racehorses that were galloping on a treadmill at a standardised speed wearing commonly-used exercise girths. All girths were of the same length and tension. Just as in the sport horse study, increased girth pressures were identified behind the elbow in the galloping thoroughbred, with pressure peaks occurring when the forelimb opposite to the leading leg was in stance (see photo).

The moment in the stride when peak pressure is seen—the point where the musculature is trapped between the front of girth and back of leg.]

Although the location of pressure was consistent between sport horses and racehorses, the magnitude of the pressures recorded under commonly used race girths was dramatically higher—and far higher than had been reported in any previous saddle study. The girth pressure mat was calibrated to manufacturer’s guidelines at a maximum of 106kPa, but in the racehorse study pressure values for a galloping horse wearing a regular girth peaked out above the highest calibration point. It was not possible to estimate the exact magnitude of girth pressure, but it is worth noting that 106kPa is already three times the peak pressure reported to cause capillary damage and discomfort beneath a saddle.

Pressure under a straight girth on a horse galloping on a treadmill was higher than the pressure mat could record.

In the second part of the experiment, the same horses were galloped over-ground in order to quantify gallop kinematics and determine if there was any change when girth pressures were reduced. Data demonstrated that a modified girth, designed to avoid areas of peak pressures, significantly improved the horse’s locomotion at gallop with increased hock flexion, hindlimb protraction and knee flexion.

Space to breathe

Girth pressures are also thought to have an influence on the horse’s capacity to breathe efficiently. One study demonstrated a relationship between increased girth tension and a reduced run-to-fatigue time on a treadmill, indicating that girths can affect the breathing apparatus of the galloping horse.

The more recent girth pressure study also identified a relationship between peak pressures in a normal girth and breathing. This study didn’t quantify respiration rate, but visual observation of the pressure mat data indicated a peak pressure on inhalation. When the horse was wearing the modified girth, the pressure spikes (speculated to be related to the intake of breath) were no longer evident.

It has been reported that the equine rib cage has a limited range of expansion directly where the girth sits. The shape and fit of the modified girth design reduces pressure from the intercostal muscles and therefore does not hinder the rib cage’s naturally occurring expansion.

The girth pressure studies in sport horses and racehorses suggest that muscle function could be highly significant in relation to the time it takes a galloping horse to fatigue.

Muscles need to contract in order to work effectively. If pressure from the girth negatively affects muscle activity, this could result in restricted function and limit the limb’s full range of motion. Subsequently, the muscles may have to work harder and, if they are required to work harder, may fatigue faster.

When scientific evidence shows that commonly used girths are compromising muscle function and restricting breathing during galloping, the advantage of the modified design becomes obvious.

Not so fantastic elastic

One anecdotal belief is that girths modified with elastic inserts offer some form of pressure relief, allowing the horse’s rib cage to expand, therefore enhancing instead of hindering breathing mechanics. However, in the sports horse research, adding an elastic component to the end of the girth did not result in increased locomotion or any alteration in pressure distribution beneath the girth. In contrast, the addition of the elastic decreased the stability of the saddle. Furthermore, new elastic girths can provide up to six inches of stretch and, as a result, are easy to over-tighten. With daily use, the elastic component of the girth weakens over time, losing its elastic properties and stretching. From a safety viewpoint, where elastic girths are being used in race training, routine checks of the stitching and elastic strength are crucial.

Anticipated pain and ulcers

In practice, without the use of sophisticated measuring systems and in the absence of skin ulcers, girth pressures will largely go undetected. However, behaviour when being tacked up, particularly when the girth is being done up, can be indicative of girth-related pain and discomfort.

Similar to humans anticipating pain, horses increase cortisol and gastric acid production, leading to gastric irritation. For horses that already have clinical signs of ulcers, this, combined with excessively high girth pressures in excess of 106kPa behind the elbow at gallop, is likely to lead to increased discomfort. As a result, health and performance are likely to be compromised.

The use of a pressure-relieving girth may be an effective tool when used as part of a multidisciplinary approach in supporting horses undergoing treatment and management of ulcers. If pressure-related discomfort is eliminated, it seems likely that the anticipation of, and response to, pain will be reduced over time.

The area of peak pressure (shown in red) caused by a straight girth is avoided by the cutaway shape of the modified girth.

The research performed on the treadmill demonstrated that a straight girth created areas of high pressures in excess of 106 kPa behind the elbow, on muscles that are vital for locomotion and respiration. …

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD —

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Substance Abuse - a new view of an old enemy

By Lissa Oliver

“I have seen so many jockeys wasting on physic go out like the snuff of a candle,” said starter and former jockey Henry Custance, in 1886. In 2016, work-rider and former jockey ‘Franck’ told Rue 89 journalist Clément Guillou, "I saw that if I drank bottles of vodka and took cocaine, I was not hungry and I urinated a lot, so I lost weight. I became addicted at 22 years old, up to three or four grams a night. Then there are the prohibited products, diuretics (Burinex) and laxatives (Contalax).

"My first Burinex, I lost one and a half kilos in 12 hours. Your heart is beating very fast, you urinate all afternoon. You still want to go, but you have nothing left.” ‘Franck’ took only five milligrams of the most powerful diuretic, prescribed for acute and chronic renal failure. "You feel your belly retract. I know the Burinex shoot my back. And since you have only been snacking for three days, you are a little tense at the time of the race. The cramps happen quickly."

If ‘Franck’ “eats like a normal human being” he weighs 68-70 kilos. He needs to be 64 kilos. But it isn’t only about weight. "Among the lads, there are many former jockeys. The weight has caught up with them, but they remain alcoholics. They work in the yard all morning, and sleep in a nine-square-metre room, because here [in Maisons-Laffitte] real estate is very expensive. Don't be fooled; if you do this job and you don't race...it’s a bad luck thing.”

It isn’t just weight. It isn’t just disappointment and loss of a dream. And, as Custance recalled in his 1894 memoir, it wasn’t only the daily glassfuls of the crude and potent laxative concoction known as ‘Archer’s Mixture’ that contributed to Victorian pin-up jockey Fred Archer’s early demise. “Unfavourable public comments made in the press or conveyed to him by trouble-making acquaintances, slander and back-biting such as it is almost inevitable for a man in his position to suffer, racked him mentally.” Today, we call that social media.

Resorting to substance abuse and becoming reliant upon its effect is as old as racing itself. The problems that drive the unfortunate to addiction have never gone away and are not going to, either. And the benefits of that addiction are hard to obtain by any other fashion.

“In racing, the call of the bottle and the threat of the scale go hand in hand. Alcohol dehydrates, so it takes you to the bathroom more easily, and acts as a pain reliever,” Manuel Aubry, work-rider, told Rue 89. “A lot of white wine and champagne because it doesn't make you fat. My weight is 73 kilos. I went down to 66.5. I was hypoglycemic.”

And there’s another factor as well. Maurice Corcos, director of the adolescent and young adult psychiatry department at the Montsouris Institute in Paris, responded, “Sports practice requires dietary restrictions. Both are self-reinforcing and addictive. Anorexia, bulimia and sports are addictions. We must add the state of elation linked to sporting success. When all these addictions are no longer enough, there may be the switch to others like alcohol and cocaine."

If the problems haven’t changed or diminished, our recognition of the symptoms have. As we can already discern from those featured here, what we see only as a problem in itself is nothing more than a symptom of several problems. The industry is tackling the symptoms stringently; but is it equipped to really prevent the problems at source?

That may not be our concern, but of considerable concern to trainers is the repercussion of staff becoming dependent on alcohol or drugs. It doesn’t only affect their timekeeping, work ethic and impact on their colleagues; the risk of cross-contamination is a major issue.

We have already seen in Britain the disqualification of a winner due to a banned substance that was traced back to the hair dye used by an assistant trainer. Last October, a point-to-point winner in Ireland was disqualified for traces of the drug Ecstasy. Veterinary surgeon Hugh Dillon stated the horse could have been inadvertently exposed to Ecstasy through human contact. The trainer was fined €1,500. Another Irish trainer saw his €1,000 fine waived having taken all reasonable precautions to avoid contamination, as his disqualified horse had apparently tested positive to caffeine from a small amount of coffee spilt on racecourse stable bedding.

In North America, a trainer was held blameless after a horse in his care tested positive for cocaine. The Maryland Racing Commission ruled, “Because of his past history and the drug in question, the groom was requested to deliver a urine sample. He refused to take the drug test but did admit that he was in possession of cocaine the day the horse ran.” As a result, the trainer was not fined, but the horse was disqualified and lost the $13,110 purse. This was in contrast to three previous positive tests for cocaine handled by Maryland stewards, who handed out 15-day suspensions despite evidence of contamination from backstretch employees.

Texas stewards absolved several trainers of any blame when six horses tested positive for the street drug methamphetamine, and human contamination was ruled as a “mitigating circumstance”. The horses were disqualified and lost the purse money earned.

When it comes to taking “all reasonable precautions”, so much is out of the control of a trainer. In addition to loss of the race and prize money, proving cross-contamination involves lengthy and rigorous investigation and testing, by which time the headlines of disqualification and banned substances may already have caused damage. And there isn’t always a simple solution.

As a trainer found out, being absolved of guilt is sometimes not enough. His filly was found to have the painkiller Tramadol in her system when she ran unplaced, thanks to a groom urinating in her box while mucking out. The trainer was fined £750 and commented, “If I put a little sign out in the yard saying 'Please don't urinate in the boxes', owners coming in here will think we're a right tinpot little firm." He instead employed a former policeman to rewrite his health and safety rules to include a rule against urinating in boxes. It was a costly experience all round.

Alcohol and drug dependency has been a recognised aspect of the racing industry for three centuries, so why is it only now becoming such an issue? Partly this is due to the introduction of testing, but partly, too, we are also more aware of the underlying causes and tragic consequences and are less willing to turn a blind eye.

Testing for alcohol and illegal substances in jockeys was first introduced in France in 1997. Jockeys were breathalysed on a British racecourse for the first time in 2003, and in Ireland in 2007. In 2000, Irish jockey Dean Gallagher became the first in France to test positive for cocaine. “Since testing began three years ago, we have never had any cases of jockeys using hard drugs," said Louis Romanet, Director-General of France-Galop, at the time. “Dominique Boeuf had problems with the police over drugs, but he never tested positive when he was riding.”

Paul-Marie Gadot, France-Galop, says, “France-Galop occasionally catches a few jockeys, often foreigners not necessarily used to French doping controls. Around a thousand riders are tested per year, not counting the breathalysers. It is not to make sure that they do not lose, because the performance is made by the horse, but we want to make sure that the jockey does not put his health in danger, that he has not taken alcohol, is not on antidepressant or has not taken diuretics.”

‘Archer’s Mixture’ and champagne diets are no longer so open that they’re considered de rigueur. Yet they remain, but now, perhaps dangerously, hidden. With stringent testing, the old methods of relief are denied. This has other consequences.

“I commissioned a survey in racing in 2015, and 57.1% of jockeys in Ireland had symptoms of depression,” stated Dr Adrian McGoldrick, the Irish Turf Club chief medical officer at that time. In the age group of 18-24, the figure rose to 65.2%. Nationally, only 28.4% of 18-24-year-olds suffer from major depression, so jockeys suffer from depression at an alarmingly higher rate than their non-jockey peers.

To whom do trainers owe the greatest duty of care—their horses, their staff, the jockeys they employ, or their owners? What happens when that duty of care gives rise to a conflict of interest?

Increasingly, apprentice jockeys are testing positive, and they should certainly rate high on that spectrum; they are the next generation of professionals coming through. But should we support, sympathise with, or admonish? What about the duty of care we owe our horses and owners?

Cocaine has been widely used by jockeys as a hunger suppressant, with high-profile names throughout Europe testing positive. Following a six-month ban in 2001, German champion Andrasch Starke was quick to acknowledge the importance of support from his trainer, Andreas Schütz. “I think that's great, and something like that strengthens. He is with me, and I am also with him. I have great appreciation for his behaviour towards me. Because I am aware that it could have been different. Suddenly I could have stood there without a job.” …

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD —

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Encouraging and maintaining appetite

By Catherine Rudenko

Encouraging and maintaining appetite throughout a season can become a serious challenge. The best planned feeding program in the world is of no use if the horse simply does not eat as required to sustain performance. There are multiple factors that can lead to poor appetite for horses in training—some relating to health, some relating to physical properties of the feed or forage, along with behavioural considerations.

What is a normal appetite?

Before we can fairly state a particular horse has a poor appetite, we must firstly have an idea of what a normal appetite range is. The horse has a given capacity within its digestive tract and an appetite appropriate to this. Horses will typically consume 2-3% of their body weight each day on a dry matter basis—in other words not accounting for fluid intake or any moisture found in the forages. This equates to 10-15kg (or 22-33lbs) per day for a 500kg-weight racehorse. As fitness increases, it is normal for appetite to reduce, and most horses will eat closer to 2% of their body weight.

The energy requirement of a horse in training is such that we are dependent on a large amount of grain-based ‘hard feeds,’ which for the majority form 7-9kg of the diet each day. With a potential appetite of 10-15kg we are, for some individuals, running close to their likely appetite limit.

The most immediate effect of a reduction in appetite is the reduction in energy intake. Horses require a large amount of calories, typically 26,000 to 34,000 cal per day when in full training. Comparatively, an average active human will require only 3,000 cal per day. Just one bowl of a racing feed can contain 4,500 cal, and so feed leavers that regularly leave a half or quarter of a bowl at each meal time really can be missing out. Forage is equally a source of calories, and a reduction of intake also affects total calorie intake.

Physical form of feed and forage

The physical form of the bucket feed can affect feed intake due to simple time constraints. Morning and lunch time feeds are more common times at which to find feed left behind. Different feed materials have different rates of intake—due to the amount of chewing required—when fed at the same weight. To give an example, 1kg of oats will take 850 chews and only 10 minutes to consume in comparison with 1kg of forage taking up to 4,500 chews and 40 minutes to consume.

Meals that require a high amount of chewing—whilst beneficial from the point of view of saliva production (the stomach’s natural acid buffer)—can result in feed ‘refusal’ as there is simply too much time required. Cubes are often eaten more easily as they are dense, providing less volume than a lighter, ‘fluffier’ coarse mix ration. Inclusion of chaff in the meal also slows intake, which can be beneficial, but not for all horses. Any horse noted as a regular feed leaver ideally needs smaller meals with less chewing time. Keeping feed and forage separate can make a significant difference.

The choice of forage is important for appetite. Haylage is more readily consumed, and horses will voluntarily eat a greater amount. The study below compares multiple forage sources for stabled horses.

Another factor relating to forages is the level of NDF present. NDF (neutral detergent fibre) is a lab measure for forage cell wall content—looking at the level of lignin, cellulose and hemi-cellulose. As a grass matures, the level of NDF changes. The amount a horse will voluntarily consume is directly related to the amount of NDF present.

Analysing forage for NDF, along with ADF, the measure relating to digestibility of the plant, is an important practice that can help identify if the forage is likely to be well received. Alfalfa is normally lower in NDF and can form a large part of the daily forage provision for any horse with a limited appetite. As alfalfa is higher in protein—should it become a dominant form of daily fibre—then a lower protein racing feed is advisable. Racing feeds now range from 10% up to 15% protein, and so finding a suitable balance is easily done.

B vitamins

B vitamins are normally present in good quantity in forages, and the horse itself is able to synthesise B vitamins in the hindgut. Between these sources a true deficiency rarely exists. Horses with poor appetite are often supplemented with B12 amongst other B vitamins. Vitamin B12 is a cofactor for two enzymes involved in synthesis of DNA and metabolism of carbohydrates and fats. Human studies where a B12 deficiency exists have shown an improvement in appetite when subjects were given a daily dose of B12 (3).

As racehorses are typically limited in terms of forage intake and their hindgut environment is frequently challenged, through nutritional and physiological stresses, it is reasonable to consider that the racehorse, whilst not deficient, may be running on a lower profile. Anecdotal evidence in horses suggests B12 supplementation positively affects appetite as seen in humans.

Another area of interest around B vitamin use is depression. Horses can suffer from depression and in much the same way as in the human form, this can affect appetite. French researchers investigated the behaviour of depressed horses, those determined as non-reactive or with low reaction to stimuli, against their response to sweetened and novel-flavoured foods. The depressed horses consumed significantly less than normal horses (4). There has been much interest in B vitamins for humans with depression as a low level of B vitamins is linked with depressive behaviour (5). Using a B vitamin supplement may also be beneficial to horses.

Digestive health

Gastric ulceration is commonly associated with changes in appetite (6). Picky eaters may be responding to the physical effect of feed digestion in the stomach. Racing feeds by design contain a significant amount of starch relative to forages, which horses are designed to consume. Starch fermentation in the stomach produces VFAs (volatile fatty acids), which can damage the stomach lining if the pH level of the upper stomach is lower than normal causing discomfort (7). The ability of the upper stomach to remain within normal parameters relates to forage intake. Normal range is pH 5-7, however with limited forage intake the pH can lower to 4. Once below this level, the squamous tissue may ulcerate for a variety of reasons including VFA production at the time of feeding (8).

The incidence level of ulceration in racehorses is high, with reports of 93% of horses having presence of ulcers (9). Not every individual shows the classical symptoms of ulcers but for any horses with poor appetite scoping for ulcers is recommended. The risk factor for development of ulcers is related to the amount of time spent in training, with every week spent increasing risk 1.7 fold (10). A horse with a change in appetite as the season progresses may not just be the result of increasing fitness but an indicator of an ulcer developing.

Feed flavouring

The use of flavouring in feed is another consideration for sparking appetite. Although traditionally mint is used as an addition to feed, more recent research into a broad range of flavours has revealed that horses find other flavours more appetising. In order of preference, horse selectively consumed a fenugreek-flavoured cereal by-product first followed by banana, cherry, rosemary, cumin and carrot before reaching peppermint. When added to mineral pellets, the most common item to be left at the bottom of a feed pot when using a coarse mix for racehorses, the inclusions of fenugreek and banana resulted in pellets being more readily consumed (11). Including a novel flavour may be enough to encourage interest in horses that are apparently off their feed for no reason.

Assessment and recommendations for horses with poor appetite

There are multiple factors that influence appetite, and improving appetite will normally require taking more than one approach to get the best result. …

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD —

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

18-40 – captivating the next generation of racehorse owners

By Lissa Oliver

A popular music festival, soon approaching its 60th year, recently generated a great deal of upset on social media with regard to the line-up. “I have been going since it started, and I have never heard of any of these bands!” said many. “Worst line-up ever! It has been getting steadily worse every year!” complained others. “Oh, wow! Brilliant line-up!” said all of the younger ones. One of them even had the sense to comment, “What were 50-year-olds saying about your favourite bands when you first started going there in 1961?”

There is a generation gap; it exists. Times change. The offside rule in football has changed many times, yet the game remains the same. So it is for horse racing; the sport itself does nothing to engender a rift between young and old. The problem seems to be in getting young people through the gates and discovering for themselves that this is something they can become passionate about. It is by no means a new problem—horse racing has historically been dominated by the over-40s audience, and that has been a perpetual worry for the industry.

According to Nielsen (www.nielsen.com) data, only golf has an older average television audience age, at 64, than horse racing. Data collected periodically shows an increase in the average viewing age of televised horse racing from 51 in 2000 to 63 in 2016—the most recent data collected. In 2016, 5% of horse racing’s audience was under 18, falling from 10% in 2000 and 7% in 2006.

Horse racing isn’t unique in this loss of younger viewers. Those who watched wrestling at the height of its television popularity still do—the average age of a television viewer of professional wrestling has climbed by 21 years since 2006 to the age of 54—the biggest age increase of any sport viewed on television.

Jesse Collings of Wrestling Inc., observes, “For WWE, the main issue for the company is that they have failed greatly to create new fans over the last two decades. Chances are if you are a WWE fan right now, you have probably been watching WWE for over 20 years. From 1997 to 2001, the average age of a WWE viewer was 23 years old—30 years younger than the current viewer today. The promotion was hot and creating new fans on a weekly basis, with a lot of young people that were getting into wrestling for the first time. Maybe they stopped when the top stars of that era retired, or they had kids, or they just got burned out by the product.”

As horse racing is currently at that same ‘hot’ promotion stage, perhaps this should stand as a future warning. It’s retention, not attraction, that should be the central focus.

The Nielsen study of 25 televised sports showed that all but one have seen the average age of their viewers increase during the past decade, as the younger generation gravitate toward digital options. This doesn’t mean they no longer watch the sports that interest them, but it does mean we can no longer rely on television viewing figures to identify our market and popularity. Attendances, therefore, become increasingly important.

This is where there is brighter news for horse racing. In Britain, the Racecourse Association (RCA) reports that the British racing crowd is younger than the overall sporting average, based on advanced ticket purchases. This has been driven by engagement with the millennial generation who are responsible for 44% of British horse racing attendees, even though millennials make up just 21% of the population.

“Engaging audiences at an early stage is crucial for the future of racing and presents a huge opportunity for us over the next 10-15 years as millennials continue to take a larger share of the leisure pound,” reflects Stephen Atkin, RCA Chief Executive. “We hope they will go on to become lifelong followers and participate more in the sport through attending, betting and even ownership or working in racing.”

Great British Racing (GBR) has invested heavily in growing racing’s younger fanbase, promoting free admission for under-18s, and during the six weeks of the summer school holidays there was a 1.15% increase in attendance at family fixtures, tripling the average growth. British attendances have increased by 5% and, importantly, retention rates have increased by 2%.

This is in direct variance to France, where attendances fell by 25% from 2000, before drastic marketing measures were taken in 2017. “The teaching of horse racing from parents to children is lost. There is a whole generation who do not come to the racetrack and who said to themselves it is an insider's environment; it is not made for us,” Grégory Garnier, head of the marketing department at Le Trot, recently told Le Figaro, that evening racing, aimed at young people, has worked best with turnover increased by 30%. The Thursday evening meetings at ParisLongchamp, begun in May 2018, attract 8,500 spectators aged 20-30.

By combining forces, the PMU, Le Trot, France-Galop, the National Horse Racing Federation and the Equidia group developed the “EpiqE Series” specifically to attract Generation Y. “We must conquer the generation of 25-45-year-olds,” says Édouard de Rothschild, president of France-Galop.

The key lies in understanding the target audience. What is Generation Y, and who are millennials?

“Boomers” (aged 50- 67) typically like activities that are more controlled and structured, they value peer competition and embrace a team-based approach.

“Generation X” (aged 35-50) like to ask questions and challenge concepts; they like to know exactly what is being offered and have clear goals. They prefer managing their own time and solving their own problems and like getting feedback to adapt to new situations. They are flexible and gender equal.

“Generation Y” (aged 13-27) are also known as millennials and are described as the most educated, entertained and materially-endowed generation in history. They have been raised in a self-educated era and are more interested in the social aspects of sports. They like to learn new things in an environment that is engaging, flexible and fun; and they want to experience new things in an environment where their ideas and opinions are heard.

A Turnkey Sports and Entertainment survey, now Marketcast (www.marketcast.com), conducted in 2016 in North America noted that the biggest deterrent to drawing Generation Y to horse racing was lack of personalities—a view shared by 40% of those surveyed. Contrary to what some in racing suggest, the short duration of the main event was only cited by 7%, and the gambling aspect was a concern of just 2%. The welfare of animals was highlighted by 17%.

This year, a survey by Marketcast Kids found that children, a group we will be looking to attract as our customers in the next decade, hold very strong views on social issues—animal rights and wildlife protection figuring high on their list of priority, above world peace, provision for the poor and climate change. Ninety-three percent of children surveyed throughout North and South America, Europe and Asia believe companies have a responsibility to directly support good causes with money, time and publicity.

This is already an idea acted upon by Britain’s “Racing Together” scheme, encouraging racecourses to engage with their local community. Racing Together and the Racecourse Association (RCA) raised over £2.2m through racecourse charitable activity during 2019 for over 250 charities, and racecourse team members volunteered more than 3,100 hours to community projects. Free curriculum-based school trips were hosted for 15,011 students, and all of this received media publicity, particularly during televised racing.

This side of the public face of racing is vital, as young people feel limited by their own means and want companies to help them take action. Of those surveyed, 87% believe they can create change, and they provided a clear priority list of what companies can do to support youth social activism:

Make products they can use to help make a difference.

Give them a free space to meet and organise.

Publicise events that kids and teens are running,

Organise after-school clubs or online groups to connect them with others who care about their cause.

Run events or fairs.

Their number one priority may not apply to our industry, but we can meet the other needs of today’s children, who are not far removed from the Generation Y we are trying to attract. A designated space at the racecourse and online group interaction offers an engagement with horse racing they themselves can run and control and can be readily supplied by racecourses, already proven in Asia.

Given that golf is the only sport attracting an older viewing audience than horse racing, it might be helpful to look at how that sector is promoting itself to Generation Y. “Get into Golf” is a programme designed not only to support golf clubs in recruiting new members and increasing membership figures and revenue, but to make golf more accessible to a wider audience. To achieve this, it focuses on recruitment, advertising and communication, both internal and external.

Its taster sessions and awareness days have been particularly successful, combining lessons with a PGA professional with volunteer activities to help integrate participants into the golf club. In 2019 alone, golf clubs running “Get into Golf” enjoyed an average conversion rate from the programme into membership of 66%.

Similarly, tennis clubs throughout Europe are also adopting a direct approach, most advertising weekly pizza party social evenings for under-21s and designating specific teen social days once a week or bi-weekly, all of which is advertised on social media, and where group pages are deployed to great effect.

The British Horseracing Authority (BHA) “Diversity and Inclusion Report 2018” identifies the need to bring horses and sporting action closer to racegoers and cites the Hong Kong Jockey Club as a good example, where virtual reality technology allows racing fans to create their own horse and set of colours and compete in their own race, in designated ‘technology zones’.

The Report also explores opportunities to collaborate with other equestrian organisations and inner-city charities and highlights initiatives such as “Take The Reins”, where horse racing is harnessed to inspire personal and social change and be a force for social good in disadvantaged communities. The sport is used to promote its values and excitement to new and under-represented communities by improving access, understanding and involvement. The feasibility of establishing an inner-city racing academy as a focal point for the next generation is also being explored.

The “Racing To School” initiative, showcasing the sport and career opportunities in schools, has been broadened to include trips to training centres and the introduction of ‘family follow up week’ during school holidays.

France-Galop and Great British Racing already promote the successful “Under 18s Race Free”, an incentive also adopted by Irish racecourses, but CEO of the Irish Racehorse Trainers Association, Michael Grassick, identifies a serious issue.

“Something that really needs to be addressed by HRI (Horse Racing Ireland) is the rule that under-18s must be accompanied by an adult,” he points out. “It’s ludicrous to turn away young people because they come racing on their own, and it needs to be sorted out at once. It’s a very serious issue. We were all as children taken racing by our parents, and we went racing by ourselves on days off from school. We developed our love of racing as children, so for the current young generation to be told they have to be accompanied by an adult, because of the betting and alcohol at races, is a joke. The barman at the races should be like any barman everywhere else and not serve anyone without age ID, and the same for betting. Stopping them at the gate is ludicrous, and we’re seeing it happening.” …

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD —

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

PET: the latest advance in equine imaging

By Mathieu Spriet, Associate Professor, University of California, Davis

Santa Anita Park, the iconic Southern California racetrack, currently under public and political pressure due to a high number of horse fatalities during the 2019 season, announced in December 2019 the installation of a PET scanner specifically designed to image horse legs. It is hoped that this one-of-a-kind scanner will provide information about bone changes in racehorses to help prevent catastrophic breakdowns.

What is PET?

PET stands for positron emission tomography. Although this advanced form of imaging only recently became available for horses, the principles behind PET imaging have been commonly used at racetracks for many years. PET is a nuclear medicine imaging technique, similar to scintigraphy, which is more commonly known as “bone scan”. For nuclear imaging techniques, a small dose of radioactive tracer is injected to the horse, and the location of the tracer is identified with a camera in order to create an image. The tracers used for racehorse imaging are molecules that will attach to sites on high bone turnover, which typically occurs in areas of bone subject to high stress. Both scintigraphic and PET scans detect “hot spots” that indicate—although a conventional X-ray might not show anything abnormal in a bone—there are microscopic changes that may develop into more severe injuries.

Development of PET in California

The big innovation with the PET scan is that it provides 3D information, whereas the traditional bone scan only acquires 2D images. The PET scan also has a higher spatial resolution, which means it is able to detect smaller changes and provide a better localisation of the abnormal sites. PET’s technological challenge is that to acquire the 3D data in horses, it is necessary to use a ring of detectors that fully encircles the leg.

The first ever equine PET scan was performed at the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California in 2015. At the time, a scanner designed to image the human brain was used (PiPET, Brain-Biosciences, Inc.). This scanner consists of a horizontal cylinder with an opening of 22cm in diameter. Although the dimensions are convenient to image the horse leg, the configuration required the horse be anesthetised in order to fit the equipment around the limb.

Figure 1: The first equine PET was performed in 2015 at the University of California Davis on a research horse laid down with anesthesia. The scanner used was a PET prototype designed for the human brain (piPET, Brain-Biosciences Inc., Rockville, MD, USA).

The initial studies performed on anesthetised horses with the original scanner demonstrated the value of the technique. A first study, published in Equine Veterinary Journal, demonstrated that PET showed damage in the equine navicular bone when all other imaging techniques, including bone scan, MRI and CT did not recognise any abnormality.

Figure 2: These are images from the first horse image with PET. From left to right, PET, CT, MRI and bone scan. The top row shows the left front foot that has a severe navicular bone injury. This is shown by the yellow area on the PET image and abnormalities are also seen with CT, MRI and bone scan. The bottom row is the right front foot from the same horse; the PET shows a small yellow area that indicates that the navicular bone is also abnormal. The other imaging techniques however did not recognize any abnormalities.

A pilot study looking at the racehorse fetlock, also published in Equine Veterinary Journal, showed that PET detects hot spots in areas known to be involved in catastrophic fractures. This confirmed the value of PET for racehorse imaging, but the requirement for anesthesia remained a major barrier to introducing the technology at the racetrack. To overcome this, LONGMILE Veterinary Imaging, a division of Brain-Biosciences Inc, in collaboration with the University of California Davis, designed a scanner which could image standing horses. To do this, the technology had to be adapted so that the ring of detectors could be opened and positioned around the limb.

With the support from the Grayson Jockey Club Research Foundation, the Southern California Equine Foundation and the Stronach Group, this unique scanner became a reality and, after the completion of an initial validation study in Davis, the scanner was installed at Santa Anita Park in December 2019.

PET at the racetrack….

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD —

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Should we fear or embrace continuing professional development?

By Lissa Oliver

There is a saying, ‘teaching Granny how to suck eggs’, which implies Granny has more knowledge and experience than we may ever teach her, and it’s a reverent approach we tend to take with any successful professional within the thoroughbred industry. Be they young or old, if they have bred or trained winners, we defer to their expertise or seek it out for our own education. And yet there’s a far more common idiom used regularly among trainers: ‘you never stop learning when it comes to horses’.

Just how do our industry professionals continue to learn? From the new ideas of the next generation coming through? From innovations in technology and food science? From networking and sharing ideas? From trade magazines such as this, bringing the latest research news? Possibly all of those; but there is one obvious source missing: the classroom.

Continuing professional development (CPD) is mandatory in many professions, and we wouldn’t expect it to be otherwise. Vets, for example, need to undertake a minimum of 105 hours of CPD in any three-year period, with an average of 35 hours per year. That’s four full days a year. Veterinary nurses need to complete a minimum of 45 hours of CPD in any three-year period, with an average of 15 hours per year. Dentists must complete a minimum of 100 hours of CPD over a five-year period and must have some CPD training within two consecutive years.

Each registered practitioner must make an annual declaration of their CPD and will be removed from the register if they fail to record CPD. They are also required to have a personal development plan (PDP) outlining specific training requirements and targets. Even following a career break, to be returned to a professional register involves evidence of compliance with CPD. And would we, the client, have it any other way?

You might argue it is to be expected of medical practitioners and agree that it’s also a safeguard for teachers and accountants, among the many professions for whom CPD is mandatory. But is it really necessary for the thoroughbred industry, which is still based very much on skills handed down through generations? How much has equine husbandry actually changed?

Possibly very little, but the business of producing and training racehorses has certainly seen a massive change in recent years. Compliance with the arrangement of working hours, new taxation methods, the safeguarding of staff against bullying, parental leave, health and safety assessment, staff induction policies, social media marketing—the list is endless, and none of the new challenges facing trainers have readymade solutions passed down from our forebears.

Closer to home in the equine world, Horse Sport Ireland (HSI) has instigated a mandatory CPD programme for all Level 1 Apprentice, Level 2 and Level 3 Coaches. HSI is keen to see all coaches progress their coaching skills, and this is the premise on which their CPD programme is based. HSI’s CPD events are a minimum of a half-day, and the minimum requirement of CPD credits is five per year. Examples of CPD are Safeguarding, worth one credit; First Aid, worth two credits; and HSI Coaching, worth three credits.

Again, it is the responsibility of each coach to maintain records, certificates and other evidence of compliance and to submit these to HSI. Anyone who fails to acquire the required credits or submit sufficient evidence will be removed from the register. Similarly, the British and Irish Pony Clubs have mandatory CPD requirements for instructors based on the same credit/point system. How much has the art of teaching people to ride changed, we may also ask?

OK, so CPD is necessary for skilled practitioners upon whom the public depends, and for teachers and coaches who need to be certain they are passing on current approved skills driven by modern standards. But how does this apply to me? Racehorse trainers fit both categories. Not all staff arrive with years of experience behind them, and the general public is actively encouraged to get involved in horse ownership. We are skilled suppliers of a public service and are expected to be trusted sources of learning for our employees.

Whether we like it or not, the modern workplace has progressed, and as trainers we are expected to progress with it. CPD is no longer simply a requirement of licencing bodies; it is expected by clients and depended upon by those to whom we owe a duty of care—our staff and horses and, most importantly, ourselves. Can we afford to be without it?

In North America, many trainers believe we can. Under some licencing jurisdictions CPD is mandatory, yet trainers still fail to attend required seminars, and the compulsory attendance is unenforced. Deutscher Galopp has a dedicated page for trainers on its website and suggests news of seminars and workshops can be found there when available, but there are currently none.

Liv Kristiansen

Liv Kristiansen, Norsk Jockeyklub, reports that other than the mandatory course to gain their licence, Norwegian trainers are equally reluctant. “We have arranged some seminars, but our experience is that trainers very seldom attend any conferences or seminars even when offered.”

“I can understand that,” reflects Michael Grassick, CEO Irish Racehorse Trainers Association (IRTA). “Many trainers are having to do most things themselves; the majority run small operations with less than 20 horses, and they’re riding out and having to be very hands-on. They haven’t the time to be away from the yard.

“Courses are a help, but it should be a personal choice; I wouldn’t like to say mandatory. Trainers do need help with things; everyday business is becoming more complicated with more documentation needed. They need help with things like litigation, health and safety, manual handling, insurance. They are well able to train horses but are needing more and more help with the business side of things. Seminars would be useful, but they would need to be held in the afternoon or evening.”

Michael Grassick,

What is it about CPD that makes us wary? Continuing professional development certainly sounds like something we should all welcome and embrace, but it hasn’t always been marketed as such. With compulsory hours and the inference that participants are merely wasting time certifying already existent skills, CPD has become something to fear and resent, akin to being taught ‘how to suck eggs’.

We should instead remember that, working with thoroughbreds, we never stop learning; and the rapidly evolving workplace brings with it an additional pressure to learn. Correctly tailored, CPD helps enhance the skills needed to deliver a professional service to our clients, staff and satellite community, such as media and authorities, and ensures our knowledge is relevant and up to date. It should help us to be more aware of the changing trends and directions of our profession. It is vital, therefore, that the accredited courses and workshops recognise and address those needs. Simply acquiring a certificate for existing skills is not enough.

CPD must be a documented process that is self-directed and driven by the participant, not their employer or licensing authority. That means that to make it relevant, trainers should be sourcing areas of learning of most interest to them and suggesting topics for workshops to be run by the licencing bodies.

This has long been the practice of the various Thoroughbred Breeders Associations, who run seasonal training programmes and workshops for participants, based on the feedback and needs of members and participants. The education programme is not compulsory, but courses and workshops are always over-subscribed and certainly the idiom of ‘never stop learning’ is embraced and practiced by those working in the breeding sector. Should the training sector be any different?

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD —

April - June 2020, issue 69 (PRINT)

6.95

Quantity:

1

Add to Cart

April - June 2020, issue 69 (DIGITAL)

3.99

Add to Cart

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Print & Online subscription

24.95 every 12 months

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Outlook for Stem Cell Therapy: its role in tendon regeneration

By Dr Debbie Guest

Tendon injuries occur very commonly in racing thoroughbreds and account for 46% of all limb injuries. The superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) is the most at risk of injury due to the large strains that are placed upon it at the gallop. Studies have reported that the SDFT experiences strains of up to 11-16% in a galloping a thoroughbred, which is very close to the 12-21% strain that causes the SDFT to completely rupture in a laboratory setting.

An acute tendon injury leads to rupture of the collagen fibres and total disruption of the well organised tendon tissue (Figure 1). There are three phases to tendon healing: an inflammatory phase that lasts for around one week, where new blood vessels bring in large numbers of inflammatory blood cells to the damaged site—a proliferative phase that lasts for a few weeks, where the tendon cells rapidly multiply and start making new collagen to replace the damaged tissue; and a remodelling phase that can last for many months, where the new collagen fibres are arranged into the correct alignment and the newly made structural components are re-organised.

Figure 1. A) The healthy tendon consists predominantly of collagen fibres (light pink), which are uniformly arranged with tendon cells (blue) evenly interspersed and relatively few blood vessels (arrows). B) After an injury the collagen fibres rupture, the tissue becomes much more vascular, promoting the arrival of inflammatory blood cells. The tendon cells themselves also multiply to start the process of rebuilding the damaged structure.

After a tendon injury occurs, horses need time off work with a period of box rest. Controlled exercise is then introduced, which is built up slowly to allow a very gradual return to work. This controlled exercise is an important element of the rehabilitation process, as evidence suggests that exposing the tendon to small amounts of strain has positive effects on the remodelling phase of tendon healing. However, depending on the severity of the initial injury, it can take up to a year before a horse can return to racing. Furthermore, when tendon injuries heal, they repair by forming scar tissue instead of regenerating the normal tendon tissue. Scar tissue does not have the same strength and elasticity as the original tendon tissue, and this makes the tendon susceptible to re-injury when the horse returns to work. The rate of re-injury depends on the extent of the initial injury and the competition level that the horse returns to, but re-injury rates of up to 67% have been reported in racing thoroughbreds. The long periods of rest and the high chance of re-injury therefore combine to make tendon injuries the most common veterinary reason for retirement in racehorses. New treatments for tendon injuries aim to reduce scar tissue formation and increase healthy tissue regeneration, thereby lowering the risk of horses having a re-injury and improving their chance of successfully returning to racing.

Over the past 15 years, the use of stem cells to improve tendon regeneration has been investigated. Stem cells are cells which have the remarkable ability to replicate themselves and turn into other cell types. Stem cells exist from the early stages of development all the way through to adulthood. In some tissues (e.g., skin), where cells are lost during regular turnover, stem cells have crucial roles in normal tissue maintenance. However, in most adult tissues, including the tendon, adult stem cells and the tendon cells themselves are not able to fully regenerate the tissue in response to an injury. In contrast, experimental studies have shown that injuries to fetal tissues including the tendon, are capable of undergoing total regeneration in the absence of any scarring. At the Animal Health Trust in Newmarket, we have an ongoing research project to identify the differences between adult and fetal tendon cells and this is beginning to shed light on why adult cells lead to tendon repair through scarring, but fetal cells can produce tendon regeneration. Understanding the processes involved in fetal tendon regeneration and adult tendon repair might enable new cell based and/or therapeutic treatments to be developed to improve tendon regeneration in adult horses.

In many tissues, including fat and bone marrow, there is a population of stem cells known as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). These cells can turn into cells such as bone, cartilage and tendon in the laboratory, suggesting that they might improve tendon tissue regeneration after an injury. MSC-based therapies are now widely available for the treatment of horse tendon injuries. However, research has demonstrated that after injection into the injured tendon, MSCs do not turn into tendon cells. Instead, MSCs produce factors to reduce inflammation and encourage better repair by the tissue’s own cells. So rather than being the builders of new tendon tissue, MSCs act as the foreman to direct tissue repair by other cell types. Although there is some positive data to support the clinical application of MSCs to treat tendon injuries in horses, placebo controlled clinical trial data is lacking. Currently, every horse is treated with its own MSCs. This involves taking a tissue biopsy (most often bone marrow or adipose tissue), growing the cells for 2-4 weeks in the laboratory and then injecting them into the site of injury. This means the horse must undergo an extra clinical procedure. There is inherent variation in the product, and the cells cannot be injected immediately after an injury when they may be the most beneficial.

To allow the prompt treatment of a tendon injury and to improve the ability to standardise the product, allogeneic cells must be used. This means isolating the cells from donor horses and using them to treat unrelated horses. Experimental and clinical studies in horses, mice and humans suggest that this is safe to do with MSCs, and recently an allogeneic MSC product was approved for use in the EU for the treatment of joint inflammation in horses. These cells are isolated from the circulating blood of disease-screened donor horses and are partially turned into cartilage cells in the laboratory. They are then available “off the shelf” to treat unrelated animals. Allogeneic MSC products for tendon injuries are not yet available, but this would provide a significant step forward as it would allow horses to be treated immediately following an injury. However, MSCs exhibit poor survival and retention in the injured tendon and improvements to their persistence in the injury site, and with a better understanding of how they aid tissue regeneration, they are required to enable better optimised therapies in the future.

Our research has previously derived stem cells from very early horse embryos (termed embryonic stem cells, ESCs. Figure 2). ESCs can grow in the laboratory indefinitely and turn into any cell type of the body. These properties make them exciting candidates to provide unlimited numbers of cells to treat a wide range of tissue injuries and diseases. Our experimental work in horses has shown that, in contrast to MSCs, ESCs demonstrate high survival rates in the injured tendon and successfully turn into tendon cells. This suggests that ESCs can directly contribute to tissue regeneration.

Figure 2. A) A day 7 horse embryo used for the isolation of ESCs. Embryos at this stage of development have reached the mare’s uterus and can be flushed out non-invasively. B) “Colonies” of ESCs can grow forever in the laboratory.

To understand if ESCs can be used to aid tendon regeneration, they must be shown to be both safe and effective. In a clinical setting, ESC-derived tendon cells would be implanted into horses that were unrelated to the original horse embryo from which the ESCs were derived. The recipient horse may therefore recognise the cells as “foreign” and raise an immune response against them. Using laboratory models, we have shown that ESCs which have been turned into tendon cells do not appear recognisable by the immune cells of unrelated horses. This may be due to the very early developmental stage that ESCs originate from, and it suggests that they would be safe to transplant into unrelated horses.

To determine if ESCs would be effective and improve tendon regeneration, without the use of experimental animals, we have established a laboratory system to make “artificial” 3D tendons (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Artificial 3D tendons grown in the laboratory are used to study different sources of tendon cells and help us work out how safe and effective an ESC-based therapy will be. A) Artificial 3D tendons are 1.5 cm in length. B) a highly magnified view of a section through an artificial tendon showing well-organised collagen fibres in green and tendon cells in blue.

ESC-tendon cells can produce artificial 3D tendons just as efficiently as adult and fetal cells, and this system allows us to make detailed comparisons between the different cell types.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD —

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

EMHF UPDATE - Dr. Paull Khan reports on the Asian Racing conference, Cape Town, stewarding from a remote 'bunker' and the 'Saudi Cup'.

By Dr. Paull Khan

ASIAN RACING CONFERENCE, CAPE TOWN

The Asian Racing Conference (ARC) is the most venerable institution in our sport. It may seem strange, but the Asian Racing Federation (ARF) is older than its parent body, the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA). Its conferences, while only biennial compared with the IFHA’s annual get together in Paris after the ARC, go back further—60 years in fact. And, because of the liberal definition of ‘Asia’ employed by the ARF, the conference found itself this year in Cape Town, South Africa, just as it had done once before, in 1997.

What might one glean from conferences such as this about the state of racing globally?

Well, attendance at the Cape Town event could be taken as evidence of an industry in reasonable health. The gathering attracted around 500 delegates from some 30 countries, but despite the Coronavirus effect, a large contingent of intended delegates from Hong Kong and smaller numbers from mainland China were unable to travel. Ten years ago, when the conference was hosted in Sydney, 550 attended from 36 countries. So, attendance has held up well over the past decade.

But the content of the conference perhaps tells a different story. Back in 2010, the ‘big debate’ centred on the funding of racing, and the relationship between betting and racing in this regard. What struck me about the subject matter in 2020 is that it was less about maximising income, more about the long-term survival of the sport. By way of evidence of this, there were sessions on the battle against the scourge of the rapid expansion of illegal betting, the threats to horse racing’s social licence in the wake of growing global concern of animal welfare and the mere use of animals by humans, and the urgent need to engage governments to retain their support for our industry.

That is not to say that it was all doom and gloom. Far from it. The conference opened with a stirring discussion of the potential benefits of 5G technology and closed with a session explaining why there is now real optimism that, after years of isolation, South African thoroughbreds will soon be able to travel freely to race and breed.

The 5G (fifth generation) standard for mobile internet connectivity is 1,000 times faster than its predecessor, can support 100 times the number of devices and enables full-length films to be downloaded in just two seconds. While the technology is already here, coverage is limited to date but is predicted to expand with searing rapidity over coming months. The implications of this are manifold for all of us. Indeed, it was said that the opportunities it presents will be like ‘a fire hose coming at you’. Potential benefits that speakers identified for all aspects of horse racing came thick and fast. These benefits include:

Real-time horse tracking, enabling punters watching a race to identify ‘their’ horse.

The ability to provide more immersive customer experiences—you will be able to ‘be’ the jockey of your choice and experience the race virtually from his or her perspective.

Hologram technology is already creating ways for music fans to experience gigs from around the world—why not horse racing as well?

Through the internet, the physical world is being ‘datafied’—great advances will flow from this in the shape of; e.g., the monitoring, through sensors, of such things as horses’ heart rates.

Facial recognition at racecourses will (privacy laws permitting) enable the racecourse to know its crowd much better.

Using heat-mapping and apps on racegoers’ mobiles, congestion control will be aided, and individual racegoers encouraged to go to tailored outlets.

The problem, of course, is that 5G’s benefits will be available for all sports and competing leisure and betting activities. In order to retain market share, racing will need to match others’ use of these new technologies. Each race is fast—it’s over in a matter of minutes. And understandably, while racing has some traits that work in its favour in the mobile age, in other respects, it is not well placed. Racing is fragmented, with no overarching governing body and many internal stakeholders bickering over intellectual property rights. For Greg Nichols, Chair of Racing Australia, “There’s an urgency in contemporising our sport”.

On illegal betting, the message for Europe from Tom Chignell, a member of the Asian Racing Federation’s Anti-Illegal Betting Task Force, and formerly of the British Horseracing Authority, was stark: illegal exchanges are already betting widely on European races. Pictures of those races are being sourced and made available through their websites. The potential for race-fixing is obvious.

Policing the regulated betting market and the identification of race-fixing are difficult enough. It becomes significantly more so in the illegal market, since operators are under no obligation to divulge suspicious betting activity and are unlikely anyway to know who their customers actually are.

BHA Chair Annamarie Phelps speaks on the ARC Welfare Panel

It was acknowledged that illegal betting, which is growing faster than legal betting, is already so big—so international that sport alone cannot tackle it. What is needed is multi-agency cooperation, which must include national governments. Indeed, the new Chair of the British Horseracing Authority, Annamarie Phelps, believed these efforts needed to be global to be effective: “if we start to close it down country by country, we’re just pushing people to another jurisdiction; if we act globally, we can push it out to other sports”, she argued.

The critical importance of horse welfare, and the general public’s attitude thereto, was underlined. Louis Romanet, Chair of the IFHA, said: “This is a turning point for our industry—much good has already been done, but there is more to do and dire consequences unless this happens.”

As an indicator of what has already been done, it is noticeable how, in recent years, a much higher proportion of the changes introduced to the IFHA’s International Agreement on Breeding, Racing and Wagering have been horse welfare focussed. For example, this year saw the banning of bloodletting and chemical castration practices—hot on the heels of last year’s outlawing of blistering and firing. Spurs have been banned this year, and it has become mandatory to use the padded whip not only in races but also during training.

For those outside the racing bubble, there would seem to be three core concerns: racing-related fatalities, use of the whip and aftercare. Much space was given over at the conference to the last of these, including a special session organised by the International Forum for the Aftercare of Racehorses, and in this area great strides have certainly been made in several countries. But presentations from Australia demonstrated just how necessary such efforts are. Work on a number of fronts in the interest of the welfare of thoroughbreds has vastly been ramped up in the wake of a number of body-blow welfare scandals, none more powerful than the sickening image of horses being violently maltreated in an abattoir. No longer will the public accept that racing’s responsibility ends when the horse leaves training. Even if it is many years and several changes of ownership after it retires from racing, if it should meet a gruesome end, the world will still point an accusatory finger at us. In the public’s eye, once a racehorse, always a racehorse. It was a fitting coincidence that, just as these presentations were being made in South Africa, across the world, Britain’s Horse Welfare Board was unveiling its major review of horse welfare—a key message that there must be whole-of-life scrutiny.

There is one very troubling aspect of all of this. Having been identified as necessary for racing’s very survival, any of these tasks—exploiting new technology, tackling illegal betting or establishing systems to trace thoroughbreds from cradle to grave—will be costly and resource-hungry to put into effect. The disparity in resources and influence of racing authorities is enormous. At one end of the spectrum, the size and national significance of the Hong Kong Jockey Club is hard to grasp: it employs over 20,000 people and last year paid €3.4bn in taxes and lottery and charitable contributions. In Victoria, and other Australian states, there is a racing minister. New Zealand has been able to boast such a post since 1990, and the current incumbent is also its deputy prime minister, no less.

At the other end, many racing authorities have but one track in their jurisdiction, exist through voluntary labour and are, unsurprisingly, not even on their government’s radar.

It would seem inevitable, without specific countermeasures, that the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ will only widen with the risk of smaller racing nations going under. It is surely desirable for our sport as a whole globally that racing exists and thrives in as many parts of the world as possible. Ensuring this is going to take much thought, will and effort.

STEWARDING FROM A REMOTE ‘BUNKER’

An oft-discussed topic in Europe over recent years is what might best be termed ‘remote stewarding’: where stewards officiate on distant race-meetings from a central location with the aid of audio and visual communications links. But it is outside our continent where you will find the pioneers of this concept. At Turffontein racecourse, Johannesburg, within the National Horseracing Authority of Southern Africa’s (NHRA’s) Headquarters, is a room from which ‘stipes’ have for some time now been linking with other racecourses across the country and sharing the stewarding duties.

South Africa has no volunteer stewards—all are salaried, stipendiary stewards and referred to universally as ‘stipes’.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD —

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Staying power - is the French staying race division running out of steam?

By John Gilmore

The European Pattern Committee's decision that three French Gp2 middle distance races and the Gp1 Criterium de Saint Cloud for two-year-olds risk to be downgraded in 2021, should come as no surprise to anyone.

A major problem has been the lack of quality middle distance horses being trained in France over the past few years, which the country was once famous for. Most of the better stallions like Galileo, Dubawi, Sea The Stars and Frankel are based in Ireland or England, which wouldn't in itself be a problem if the majority of the foals born from French mares who cross the shores to be mated with them, ended up finally being trained in France. The truth is many don't, and it's a pattern that's been getting worse over the years with foreigners from around the globe, buying all the commercially bred top-priced yearling horses.

Earthlight winning the Prix Morny. The only French trained Group I winner at Deauville last August

Arqana can be well satisfied with last August's three-day yearling sales. Overall turnover rose 14.8% to €42,789,000 from 228 yearlings sold, two less than how many went through the ring the previous year. But whether it's also good for French racing is highly questionable. Once again Ecurie Des Monceaux led the way with 28 yearlings, which sold for a total of €9,975,000, including the two highest Lot 147, a Galileo colt , sold to Japanese trainer Mitsu Nakauchida for €1.5m and Lot 148, a filly by Dubawi, bought by Godolphin for €1.625m. Emphasising the studs’ trusted formula of mating, the majority of their mares with top Irish and English stallions.

Of the 20 horses sold through the ring for €500,000 or more last year, all were bought by foreign buyers and only three sired by French based stallions: Siyouni, Shalaa and Le Havre for €650,000, €600,000 and €500,000, respectively. As most of the horses are unlikely to be trained in France, it's hardly positive for maintaining a healthy quality number of racehorses in France and as a consequence is somewhat negative for the future breeding industry, when needing to replace breeding stock in the future.

Significantly, all but one of the American bloodstock agents present were GENERALLY buying only top quality fillies for their clients, not only for racing but also with future breeding in mind. This is a trend that has been increasing at European yearling sales over the past few years to top up the short supply of turf-bred quality US mares.

The negative quality of top-class horses in France is evident looking at French track results over the past few years with British and Irish trained horses taking a large slice of the Group races in France.

At Deauville in August last year, only the André Fabre-trained Earthlight (Shamardal) prevented a clean sweep of the five Gp1 races run there by English and Irish trained horses. French trained horses won their five Classic races in 2019, but ended up winning only 12 of the 28 total annual Gp1 races in France with foreign-based horses taking the rest. This was inferior to the previous year when the French won 14 of the 27 Gp1 races held that year.

The extra Gp1 in 2019 being the Prix Royallieu run at ParisLongchamp over the Arc weekend, which was upgraded to Gp1 status and its distance extended from 2,500m to 2,800. In the past two years the race has been won by a British- and Irish-trained horse. It broke a six-time winning sequence of French-trained horses, who had also won 15 of the previous 17 runnings since 2001.

Roman Candle winning the Prix Greffulhe Group 2. The race is under threat for downgrading in 2021.

In fact there has been a notable descending trend of French-trained Gp1 victories since 2011, when they won 22 of the 27 races on their soil. For the full picture of all Group races, it's a similar pattern, with French-trained horses victorious in 93 from the 110 on offer in 2011, down to 72 out of 115 Group races last year.

All in all, it's not too much of a surprise that the European Pattern committee is looking to downgrade the Prix Grefulhe Gp2 French Derby trial, which admittedly was won by the Niarchos families Study of Man two years ago, winning easily in a small field. The colt subsequently went on to capture the Prix Du Jockey Club but has not done much since. Last year the race was won by Roman Candle, who later finished 5th in the Jockey Club and 4th in the Grand Prix de Paris. Downgrading is not the only major issue here, but more so the weak fields, notably in the past two years, shows the lack of depth in quality middle-distance horses in France.

When you consider that in the past, both the Prix Grefulhe and Prix Du Jockey Club were won by the likes of Peintre Celebre, Montjeu and Dalakhani who all went on to win the Arc de Triomphe and Pour Mol completed the Grefulhe and English Derby double before having a training accident. All horses had one thing in common: they were all owned by owner/breeders.

The key factor is even owner/breeders who can take more time with racehorses have adapted to the change in the Jockey Club distance from 2,400m to 2,100m in 2005, which has led to them copying the commercial market and breeding shorter distance horses. Notably, French owner/breeders like the Aga Khan and Wertheimer, by their own high standards, have not produced a top classic middle-distance performer in the past few years. It is hardly a coincidence that since 2005, the winner of the Prix du Jockey Club has never gone on to win the Prix De L'Arc de Triomphe. By contrast, in the previous 13 years, three horses: Peintre Celebre 1997, Montjeu 1999 and Dalakhani 2003 did the double.

It would appear the prophecy made by the late French journalist and historian Michel Bouchet in May 2016 rings true. “It was a grave mistake to shorten the distance of the Prix Du Jockey Club race for the French breeding industry as it’s now possible to win the Poule D'essai des Poulains over 1,600 metres and Prix Du Jockey Club with the same horse.” Three did it: Brametot, Lope de Vega and Shamardal. “All the trainers I know will regret the change, and it will only encourage breeders to produce fewer middle-distance performers."

This emphasis on the commercial markets’ influence on breeding increasingly shorter-distance horses can be clearly shown by last year's Arqana August yearling sale over the three days. …

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD —

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Introducing ‘Thoroughbred Tales’

By Sally Ann Grassick

The world of racing and breeding has been my home for my entire life. I am lucky enough to have grown up in this wonderful industry that has not only provided me with a career and the opportunity to travel the world but has also introduced me to some of my closest friends and even my boyfriend. After all of this, I feel as though I owe something of a debt back to the industry. We are ultimately just custodians of this great sport, and it is our duty to pass it on to the next generation in as healthy a state as possible.