Alan Balch - The stress test

Article by Alan F. Balch

My old horse trainer, one of the wisest people I ever met—and I find many trainers to be so wise, way beyond their formal educations—used to define stress this way: the confusion created when one's mind overrides the body's basic desire to choke the living [bleep] out of some [bleep] who so desperately needs it.

Any trainer reading this will immediately recognize the sensation, surrounded as he or she is by countless other “experts” (at least in their own minds): regulators, do-gooders, gamblers, veterinarians, reporters, owners, blacksmiths, hotwalkers, entry clerks, and track officials—to name only a very few categories of her or his advisers.

Everyone else in racing these days (not to mention virtually everyone else on Earth) is experiencing that same sensation. Our mutual feelings of stress are ubiquitous—that is to say, they’re everywhere in virtually everything we’re doing.

I can remember a time, not that long ago, when people went to the races, or owned horses, to get away from politics. And stress. The objectivity of the photo-finish camera, invented nearly a century ago now, was a welcome relief from all the conflicting opinions outside the track enclosures. And my $2 was just as valuable as Mr. Vanderbilt’s.

To be certain, there have always been politics within racing—our own politics. And gradually, with politically appointed state regulators, non-racing politics, real politics, became more and more intrusive as the decades marched on.

What we have witnessed in the last few years, however, is something new. Or, perhaps, a throwback to the early 1900s, when much of American racing was simply abolished in the name of “reform,” which a “reform” movement later led even to prohibition! It’s perhaps instructive that prohibition of alcoholic beverages ended about the same time that modern pari-mutuel betting on newly approved tracks began in the 1930s.

I’m not sure that what we’re witnessing now in racing—the advent of national, federal legislation to accompany and supplant state-by-state regulation—will be as cataclysmic for racing as what happened before in the name of “reform,” but I’m also not sure that it won’t be.

What it comes down to is this: how much reform did or does present-day racing really need? Are the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority (HISA) and its bureaucratic bedfellows actually going to result in whatever reform is really necessary? Or, are we going to fail this stress test?

The Jockey Club and Breeders’ Cup—those august, elite, and self-righteous bodies who always claim to know what’s best for racing—now find themselves arrayed against the National Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association and the Association of Racing Commissioners International. The latter can be equally self-righteous and are accompanied by some state regulators, but have no august or elite pretensions. Quite the opposite, in fact, they claim to represent “the people.” Which is to say, bluntly, the non-elite. And let there be no mistake: in racing as in all things, the less-than-elite vastly outnumber the elite. The taking of sides we’re seeing leads to absurd ironies: one vocal HISA supporter dared to scorn the Kentucky HBPA for not being democratic enough . . . apparently not realizing that The Jockey Club, prime mover of HISA, is perhaps the least democratic organization on the globe, with the possible exception of the Catholic Church.

More importantly, the top of any sport’s pyramid is very, very tiny indeed, and isolated, unless it has a broad and sturdy foundation with ready and fair access to the top. Those at the tip-top would do well to consider that fundamental fact. In American racing, remember that those graded stakes purses are funded by how much is bet on the overnights—meaning, for the most part, non-elite and lower level claiming races—which need robust field sizes to attract sufficient handle. Those are the trainers and owners represented by the organizations who are questioning the necessity and implementation of several supposed HISA “reforms.”

We hear these reasons for racing’s supposedly necessary reforms. First, we need to stamp out cheating. Second, we need to better protect the welfare of horses. Third, we need uniformity of racing rules throughout the country.

Following the experience of the last year or so, does anyone now seriously believe that adding a new layer of national bureaucratic and governmental oversight to the state oversight and regulation we’ve had since the 1930s will lead to greater uniformity, rather than more complexity, confusion, and cost? Predictably, uh, no. And, in the bargain, just what is happening to the total cost of racing regulation and oversight?

Equine welfare? To the extent that the rest of the nation expects to be required, for the most part, to follow California’s progress, this could be a positive. But is it outweighed by resulting confusion, misunderstanding, and outright resistance to its very necessity, practicality, and incremental costs? Why were so many complex regulations that were not in dispute replaced by even more intricate new language and protocols that indicate lack of fundamental horsemanship?

Finally, the worst self-inflicted wound, the perception that cheating is rampant in racing, repeated endlessly and without proof by The Jockey Club, in its anti-Lasix crusade. Yes, the authorities discovered and proved a cheating scandal via wiretaps intended for another purpose. So, please point us to the armor in the HISA hierarchy of complicated supervision that will prevent such an outrage from happening again.

What’s to be done? Well, we can continue to hope this bronc can be broke . . . and be thankful our cowboy is mounted on a horse instead of a tiger. If he is.

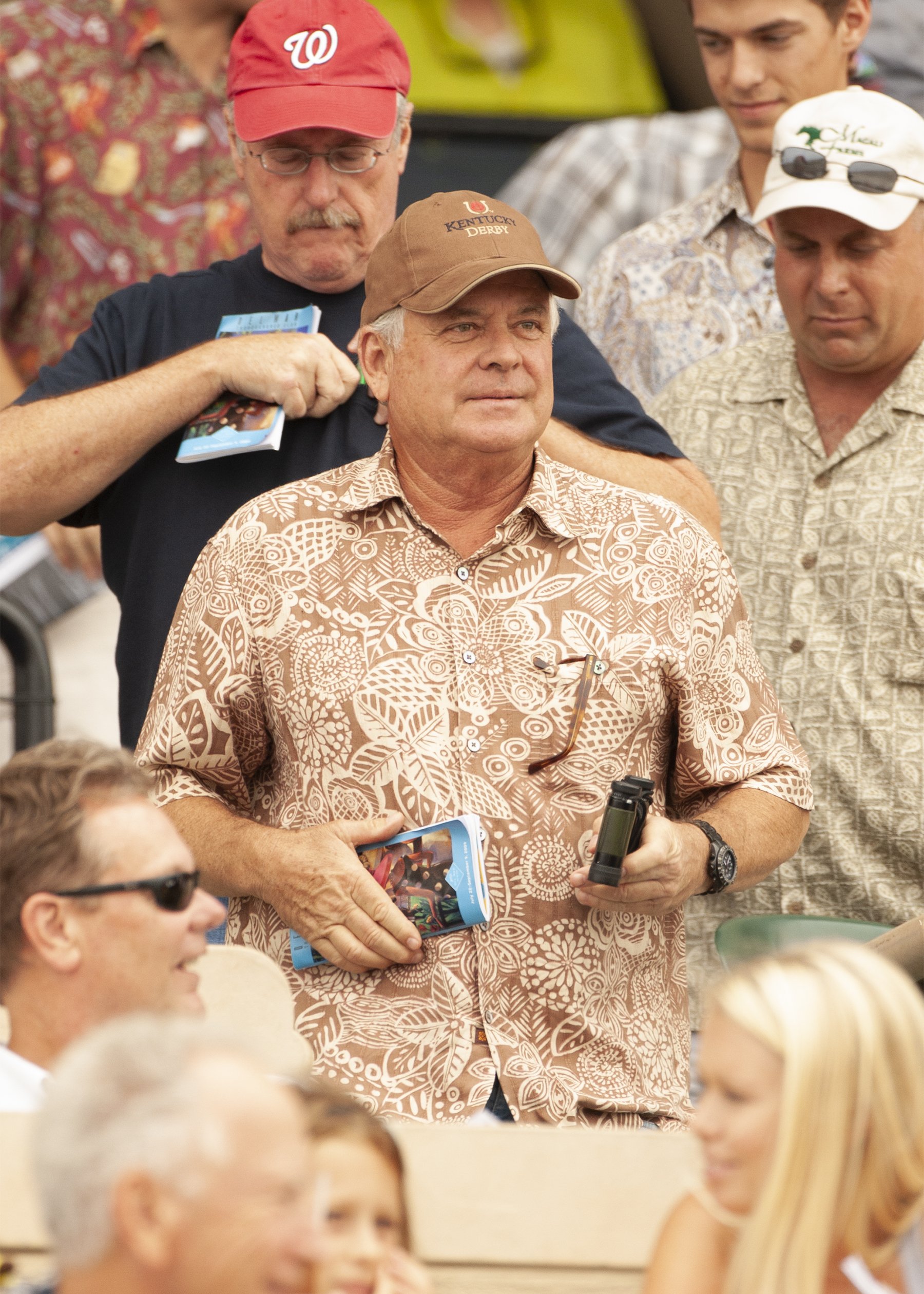

John Alexander Ortiz - the trainer of Barber Road - has plenty to look forward to.

MY WAY

By Ken Snyder

John Alexander Ortiz has two favorite memories from his first Oaklawn Park meet in 2017: listening to Frank Sinatra’s signature song, “My Way,” on the eight-hour drive back to Lexington from Hot Springs, Arkansas after the meet and getting some advice that he has never forgotten.

“Steve Asmussen and I were in a race together. He ran third and I ran fourth; and [as] we were walking back to check our horses after the race, we happened to walk side by side. Steve and I didn’t really know each other that well at the time, but I like to talk a lot, so I asked him, ‘What advice would you give a young trainer?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Stick to your guns. Nobody knows your horses better than you do. Don’t let anybody else tell you where to run them. Don’t change your system. Be who you are.’”

Ortiz may have also interspersed “My Way” with whistling a happy tune on the way home. He saddled eight winners in 46 starts at Oaklawn, for a 17%-win percentage. That’s very respectable for a trainer in only his first full year on the racetrack. He went on to earn $688,013 for the year—an enviable figure for any new trainer.

“His way” and the advice he got at Oaklawn also produced impressive results this past year: $2,614,398 compared to $1,094,092 in 2020. Surpassing even that accomplishment, perhaps, is an innovation in barn management that may have other trainers shaking their head in amazement, others pretending they didn’t hear about it, and still more near Ortiz’s barn keeping a close watch on their own barn help.

“I quit paying the help by the number of horses that grooms were taking care of. Instead, I gave everybody a yearly salary. If you’re doing six horses, or seven or eight, or four horses, you’re going to get a yearly salary—the same paycheck,” he said.

The salaried system solved a chronic short-term problem of finding barn help and the long-term problem--equally, if not more importantly—of keeping barn help.

The closure of Churchill Downs this past summer for the new turf track installation was the time for Ortiz to launch his system. He is based in Lexington and had stabled during summers at Churchill Downs. Barn help didn’t want to travel to Colonial Downs in Virginia where Ortiz and many other trainers had to locate. “We went there with 27 horses and only two grooms. We didn’t have any hotwalkers,” he said. Aside from the horses, the barn was Ortiz, three exercise riders, an assistant trainer, a foreman and the two grooms.

With all-hands-on-deck required, the traditional pay structure of pay-per-head went out the proverbial window followed by job descriptions.

Ortiz described the new system as “a test run that was scary.

“Nobody was assigned a specific horse. My brother [Daniel, Ortiz’s assistant trainer] and the grooms would walk down the line and muck stalls together. Daniel and the exercise riders would walk hots, help catch horses and fill the water buckets.

“When everybody was secure in knowing they were going to get paid a certain amount, they were happy to do whatever it took to get the job done.”

The system continued for a variety of reasons, primarily among them that it worked. The barn workers loved it. It also solved issues and problems that have always existed in racetrack barns.

“Normally, a groom gets a job taking care of five, six, seven horses; and they get paid by the head. Usually, it’s about $110, $120 per head per week. I realized that there was a lot of juggling keeping track of it—how many horses this guy did, how many horses that guy did—and you can get a little bit of jealousy: ‘Why is that guy grooming four horses, and he’s grooming seven?’” said Ortiz.

The same check for grooms eliminates all that,” he said. Likewise, all hotwalkers, exercise riders, foremen and assistant trainers are paid the same.

John and Daniel Ortiz

Salaries also minimize one hiring obstacle: Ortiz has had to turn away people who have told him, “If I can’t groom seven horses, I can’t work for you.”

Post-Colonial Downs, and with a full complement of help, the system and benefits from it continued. “With a salary, they’re willing to help me do extra things they normally haven’t had time for or don’t want to do because ‘it’s not my job.’ Those words don’t exist in my barn,” said Ortiz.

He freely admits he is “over-paying” barn help. “I’ve had grooms make up to $1,200 a week in pay. If they want to do laundry, I’ll tack on $200, do night watch: $200, walk a horse over and back for a race: $40.

Workers traveling with Ortiz from meet to meet can make the following annually: exercise riders: $40,000 to $42,000; grooms and foremen: $34,000 to $36,000; and hotwalkers: $24,000 to $26,000.

“Not only do they have a good yearly salary, but at the end of the year, I gave everybody a bonus. I know how hard everybody worked last year. I know how hard they worked for me.”

The key question—Are you getting it back in win totals and earnings?--prompts an instant answer from Ortiz: “One-hundred percent, yes.”

The exact number, of course, is incalculable.

“I want to believe we’re having a lot more success because everybody in my barn is a happy worker. Everybody wants to see us succeed. They support me because I support them. I think that’s where I get the biggest return.”

“Success” in 2021 is understating it. The increase from 2020 was just short of a whopping 139 percent—more than enough to take on higher barn pay.

If any other trainer has paid salaries rather than weekly, by-the-head wages, the affable Ortiz hasn’t heard of it. “It makes more sense to me to have reliable help than a bunch of people randomly here, coming in to get a paycheck. When everybody is secure financially, people seem to concentrate on what they’re doing.”

The change in how he paid help also comes from experience. Since being on the racetrack, Ortiz (not related to jockeys José and Irad Ortiz, as he is often asked) has worked every job in the barn including exercise rider. He knows well the ups and downs of financial fortune and constant worry about finances. “Hard-working people—the ones that really put their blood, sweat and tears into this—deserve to be secure financially. They have families.” Losing horses from the barn through a claim, for example, and the pay that goes with it, he added, is the “one thing that scares the help on the ground.”

John Ortiz and Sandra Washington, barn foreman

Ortiz is the son of former jockey Carlos Ortiz, who rode in Colombia before moving with his family to the U.S. to ride here. Embarking on a career in 1988, Ortiz rode at New York and mid-Atlantic tracks. A spill that broke his femur ended his jockey career but led to exercise riding for Bill Mott for 15 years. Working for Mott brought his son John into contact with the legendary trainer.

As a small boy, he would accompany his father to the racetrack. “I was introduced to racehorses through Bill’s barn,” Ortiz recalled.

“One summer at my dad’s birthday barbecue with trainers, jockeys, agents, etc., we were sharing horse stories, and Bill Mott looked at me across a table and asked, ‘What are you doing this summer? Why don’t you come and work for me?’”

Ortiz was 15 years old and walked hots for Mott that summer as well as on weekends. He said he fell in love with racetrack barns that summer, but with “an itch to ride horses like my dad. Bill got me on my first racehorse.”

He also wanted to know everything about barn operations—the foundation for his career as a trainer. Even though he did not groom horses, he talked to those who did to learn everything he could about it. “I was always interested in becoming a trainer. Even if I was a jockey, I knew it wouldn’t be long term because of my weight.”

As a kind of “plan B” to a jockey career, Ortiz spent a year at a trade school learning to be an auto mechanic. Jobs, however, were scarce after his training.

“My family moved to Ocala in Florida. I stayed back, and I couldn’t find a job as a mechanic. My dad said, ‘I left the helmet. I left some boots and the vest. Put ‘em on and go freelance. If you want to stay in New York, find your way.’”

“I breezed my first horse for Dominic Galluscio. He taught me how to breeze and gave me an opportunity.”

When Mott returned to New York from a winter in Florida in 2006, Ortiz went to work for him as a foreman and exercise rider. “I loved working for him. I learned horsemanship, which is rare nowadays,” he said.

As important as Mott was to him, his former assistant trainer, Leana Willaford, was the most important influence. “Being under Leana, I learned all the tricks of the trade. I still use techniques and knowledge she gave me, and I’m forever grateful for that.”

In 2008, Ortiz went to work for Graham Motion at Palm Meadows in Florida and Fair Hills in Maryland and got his assistant’s license under the British trainer. From Motion, he said “I learned organization…what it takes to run a barn.

“Everybody had a task, and it was all charted. How he ran his barn was like a business. Everything I do is on the computer, on a chart.”

After a year-and-a-half with Motion, Ortiz went to work as an assistant for Kellyn Gorder. “I’ve worked for some really great trainers—Bill Mott and Graham Motion—but working for Kellyn was the best experience in my lifetime.

David Vincente

“I got to experience a new side of horses: the yearlings, the two-year-olds, and working for farms like WinStar, Dixiana and Three Chimneys.

“I was able to see horses coming off rehab and how to develop the babies. That was one of the key elements that I learned from Kellyn.”

The best thing he ever learned from Gorder, however, may have been something intangible that he carried into his own stable and that may have been a contributor to a switch to paying salaries to barn help. “We would disagree on stuff, but he told me one day, if we didn’t disagree, we weren’t working together. His ideas became my ideas and my ideas became his; and again, that’s where I developed a mentality that this is a team effort.

“It’s not about my name on a big board across my barn.” He means that literally.

“My logo isn’t letters of my name; it’s two lines, two slashes. My hotwalkers, my grooms, my riders, my foreman Sandra Washington, assistant trainers Lindsey Reynolds, Felipe Nichols, and Daniel Ortiz—we all work here in parallel with each other. We don’t cross each other. I’m one of the green stripes, they’re the other, and we’re always side by side.”

Five years after the advice from Steve Asmussen, Ortiz refers to it often. “In 2021, there was a little dry spell in the summertime. I’m walking with my head down kicking rocks and thinking, ‘What am I doing wrong? I gotta change the feed program? We gotta’ do something.’ And then that’s when Steve’s advice popped up in my head: ‘Don’t change anything; stick to your guns.’

“I stuck to what we were doing. It wasn’t that we were having a slow summer. We were having a successful summer, hitting the board in $100,000 races. We weren’t winning that much, but we were in the right races.”

Asmussen’s counsel came to mind again more recently. Mucho, who came to Ortiz’s barn in 2021, had never won at a distance over six furlongs and had never raced longer than seven. “I put him in a mile race [the Fifth Season Stakes at Oaklawn on January 15 of this year], and I had a lot of people ask me why I’m stretching him out. ‘You shouldn’t do that; he’s a sprinter.’ No, I’m sticking with my guns. ‘He’s going to go two turns.’ The horse got beat by a neck. I knew my horse. That’s where I was reminded of what Steve told me.”

Mucho, by the way, earned $335,090 in 2021 in 10 starts for Ortiz after earning $350,829 in three years over 19 starts.” The right races, indeed.

The goals? “This year at Oaklawn is to always win a couple more than the year before. We won 15 last year. This year, we’re looking at 20.

“We’re also going to focus on the Breeders’ Cup. That’s the main goal.”

Right now, Ortiz also has a horse on the Derby trail—Barber Road—who at time of writing, has now finished second in three straight stakes races, including an impressive late running performance in the Gr. 3 Southwest Stakes at Oaklawn Park in late January. “Pretty good for a $15,000 weanling,” said Ortiz.

Could Ortiz be singing “My Way” again after this year’s Kentucky Derby or Breeders’ Cup? We shall see.

Diversification of the Thoroughbred Sire Lines

By Nancy Sexton

From the time the breeding of racehorses became a more commercial pursuit, bloodlines have ebbed and flowed freely across differing racing jurisdictions. The export of various high-profile horses out of Britain to North America during the first half of the 20th century added weight to the development of the American Thoroughbred, giving it a foundation from which to flourish. And when more American-breds came to be imported back into Europe, the British and Irish Thoroughbreds benefitted as well.

All the while, it stands to reason that some sire lines will strengthen and some will die out. Some of those that lose their vigor in one nation might thrive in another. Others will merely be overwhelmed by a more dominant line, as was the case with game-changer Northern Dancer.

A glance at the leading North American sires’ list from 1972 reveals quite how much the Thoroughbred has changed in 50 years. Round Table, Claiborne Farm’s brilliant son of Princequillo, sat at the top with approximately $2 million in earnings ahead of Hamburg Place’s T V Lark, a son of the Nasrullah stallion Indian Hemp. Princequillo and Nasrullah, both of whom stood under Claiborne management, were dominant influences of their day but interestingly each of the top five stallions that year—Herbager, Beau Gar and Count Fleet completed the quintet—represented different sire lines.

Is today’s Thoroughbred a melting pot of fewer viable lines? The 2021 North American champion sires’ table would suggest that might be the case—its top ten containing four male line descendants of Northern Dancer (Into Mischief, Ghostzapper, Paynter and Hard Spun) and four belonging to Mr Prospector (Curlin, Speightstown, Munnings and Twirling Candy).

Of course, given how each surviving branch of Northern Dancer and Mr. Prospector has evolved over time erodes the importance of comparing different representatives; Into Mischief, as a great-grandson of Storm Cat via Harlan’s Holiday, is a very different beast to Awesome Again’s son Ghostzapper as is Curlin to Speightstown and his son Munnings.

Conspicuous by its absence, though, is representation from the once vibrant Hail To Reason line, its most high-profile representative being the veteran More Than Ready in 26th place. Caro’s line is prominent via the deeds of top ten stallion Uncle Mo, although whether that horse can be classed as a typical representative of that line is a moot point. The In Reality sire line, which traces back to Man O’War, remains relevant primarily through Tiznow. However, it doesn’t take too much imagination to envisage it petering out in the near future, much like that belonging to Princequillo, Ribot, Buckpasser and Bull Lea before it.

In Europe, the situation is much the same, dominated by Northern Dancer influences descending from Sadler’s Wells, in particular Galileo, and Danzig, who is at his strongest via Danehill and Green Desert. The outlier at the top end of the market is Mr. Prospector’s great-grandson Dubawi.

Sadly, those lines descending from the likes of Mill Reef, the last British-based champion sire prior to Frankel, Blushing Groom and Sharpen Up today hang by a thread. Others, such as Dante and Habitat, have more or less died out across Europe.

Fiona Craig (right) with Molyglare Stud’s Eva-Maria Bucher-Haefner.

“It has definitely changed,” says Fiona Craig, advisor to the Irish-based Moyglare Stud Farm. “Success breeds success, so to some degree the situation is maybe better because of the dominance of the more successful bloodlines. However, as a result, we may well all lose some of the genetic variation that is so vital for the vigor of a bloodline. It is difficult to fully evaluate at this point as it may take another 50 years to see the effect of the current concentration of bloodlines.”

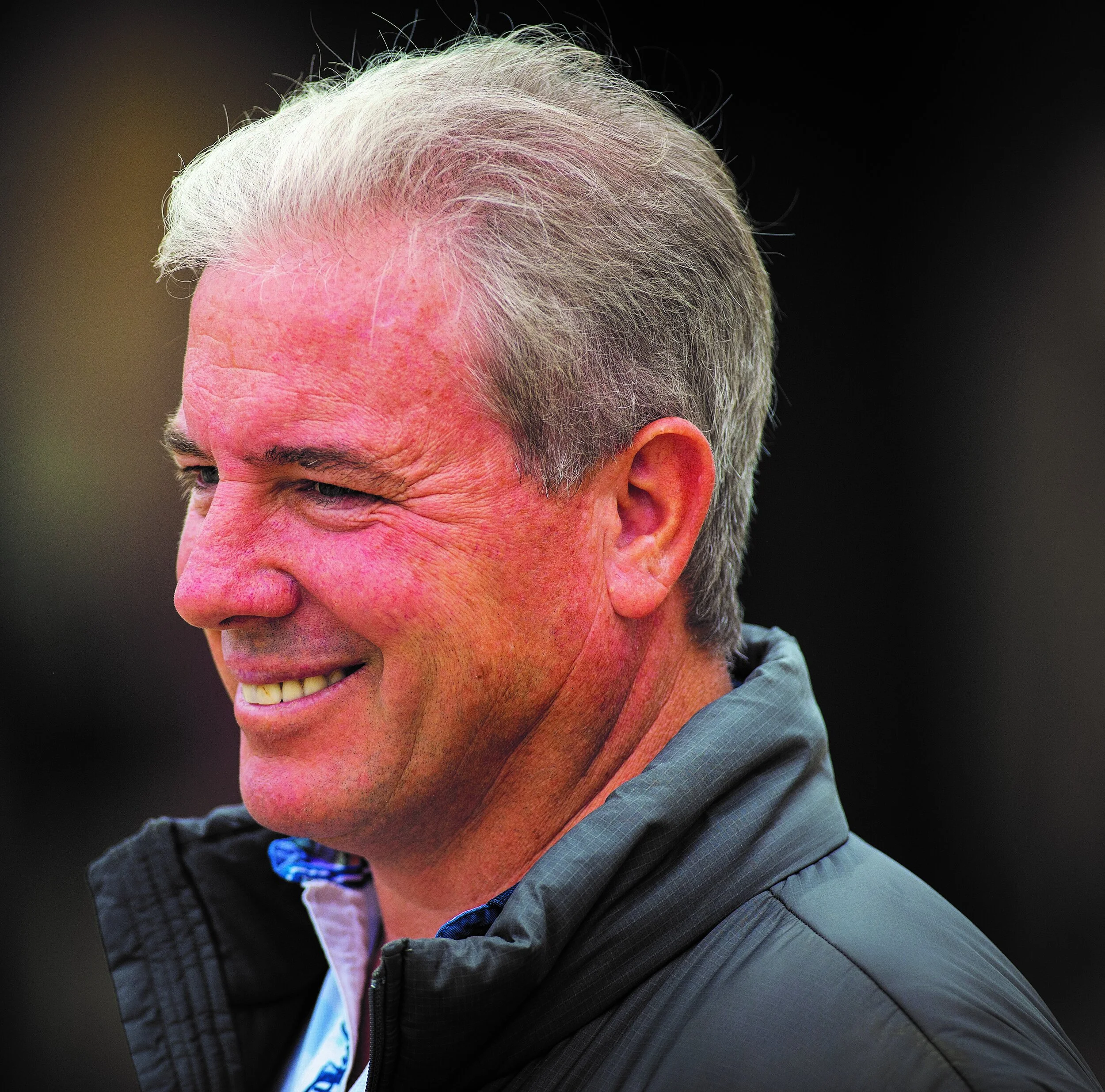

Duncan Taylor of Taylor Made Sales goes far back into the 20th century, pointing to the success of the Phalaris sire line, and its subsequent concentration, as a catalyst for the current situation.

“From 1956, the leading sire by earnings for each year since tells the story of the Thoroughbred breed and its evolution,” he says. “Speed has been the centerpiece of the story. During this 65-year period, the leading sire list has been topped on only eight occasions by stallions from sire lines other than the Phalaris paternal line. Princequillo (1957 and 1958), Ambiorix (1961), Round Table (1972), Dr. Fager (1977), Nodouble (1980), His Majesty (1982) and Broad Brush (1994) are those eight sires.

“Every other time it has been led by a Phalaris line stallion—Northern Dancer, Mr. Prospector, Bold Ruler and Hail To Reason. If you look back at the leading sires list by earnings for 2021, you see that all bar one of the top 50 stallions traces back to Phalaris: 19 of the 50 trace through Mr. Prospector, 16 through Northern Dancer, 11 through Bold Ruler, two through Hail To Reason and one through Caro. Only the In Reality line, represented through Tiznow [in 45th], does not trace back to Phalaris.”

Taylor adds: “Phalaris was a modest racehorse at stamina distance. As a four-year-old, his trainer [George Lambton] turned to sprint races where he won seven of nine starts and was ultimately crowned England’s Champion Sprinter. As a five-year-old, he became known for his ability to carry more weight than his competitors, doing so with brilliant speed. He went on to become a leading sire of two-year-olds in 1925, 1926 and 1927. He was Champion sire in England in 1925 and 1928.

Duncan Taylor

“What I see in Phalaris and what I have learned about the customers that create the “bullseye market” for buying a yearling in America are very similar. Our horse-buying customers want early two-year-old performers with speed, and they like it when the horse can go on and race at three. They would love for that fast two-year-old to be able to go on and win up to a mile-and-a-quarter at three. Phalaris and his offspring have delivered the speed necessary to put most of the other sire lines out of business. You will still see these other sire lines in pedigrees, but not as the paternal sire line.”

Globalization

Whatever way you look at it, globalization of the business has also been a driving force. On the one hand, it has allowed international breeders access to different bloodlines. On the other hand, it has been a major factor in the commercialism of the industry; once breeding racehorses became big business, fashion gained a new importance.

“The pendulum swings back and forth,” says Dermot Carty, director of sales at Adena Springs in Canada. “For example, one of the biggest influences during the 1930s and 40s was Hyperion. His son Khaled came to America and with success; another son Star Kingdom was successful in Australia; and then Aristophanes stood in South America where he sired Forli, who then came back to stand in Kentucky.

“With the international economics of the 1940s, 50s, 60s, there was a huge movement of horses, mostly back into North America. Then it went the other way—the Sangster group and the Maktoum family were driving forces into sending those bloodlines back to Europe. And all the while, Japan has been importing a lot of bloodlines and with great success—that was obviously how they came to have Sunday Silence.”

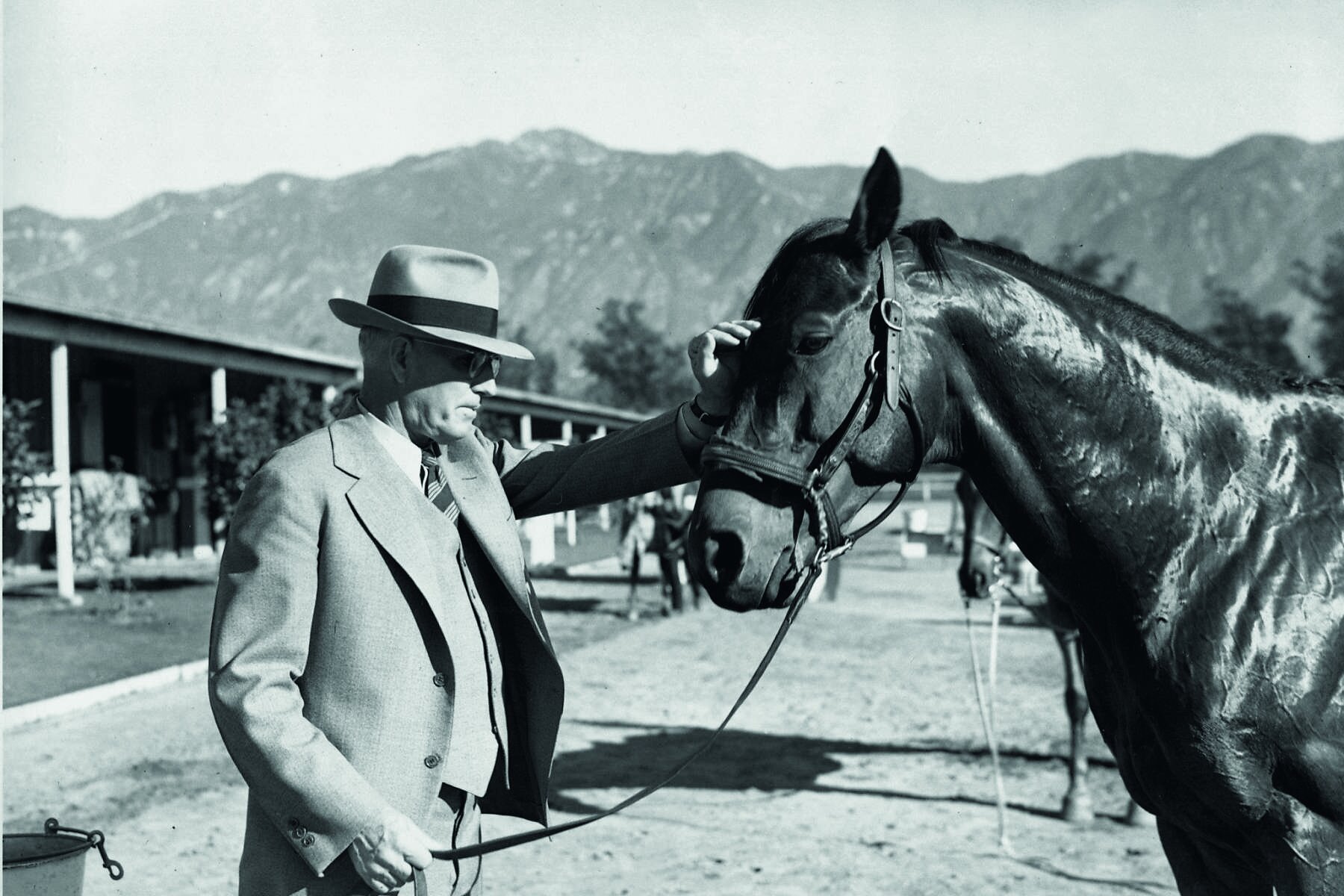

Headley Bell of Mill Ridge Farm in Kentucky concurs.

Headley Bell of Mill Ridge Farm, Kentucky

“My grandfather [Hal Price Headley] imported Order out of England and from him bred [champion] Ornament,” he says. “Then he bought Pharamond from Lord Derby and imported him to stand in Kentucky, where he sired champion Menow [sire of champion Tom Fool, in turn the sire of Buckpasser].

“We go through these different phases, and we get these cycles. You look at what John Gaines did at Gainesway, Leslie Combs at Spendthrift and before that Bull Hancock at Claiborne. They tapped into the British Stud Book and reaped the rewards—and that was a long time ago.”

Such cycles have underpinned the development of the breed, initially allowing for more variety. When Never Say Die won the 1954 Epsom Derby under Lester Piggott, he became the first American-bred winner of the race since Iroquois in 1881.

Columnist Frank Jennings, writing at the time in the Thoroughbred Record, noted that: “Never Say Die did a great deal toward changing this thought [that an American-bred would not be able to win the Epsom Derby] and at the same time provided a fine example of the fact that American bloodlines, when properly blended with those of foreign lands, can hold their own in the top company of the world.”

Just over 40 years later, the race boasted a further 11 American-bred winners as well another, Nijinsky, who had been bred in Canada.

“Properly blended” is a key phrase in Jennings’ text, with the industry’s global nature allowing for differing lines to blend in elsewhere to the point that it's not uncommon nowadays for a horse’s background to host European, North American, Japanese and/or Australian-bred names.

“It is important not to underestimate just how much the mare population matters to a stallion,” says Bell, “and how he might blend. We stood Diesis at Mill Ridge Farm—he was a champion two-year-old in Britain by Sharpen Up; and when he came here, he was provided with those American speed mares. And it clicked; it worked for him.”

As Carty notes, Adena Springs’ stalwart Silent Name is another fine advertisement for a Thoroughbred melting pot. One of the first sons of Japanese supersire Sunday Silence to stand outside Japan, the Gr. 2 winner is a proven Gr. 1 stallion and sits perennially among the leading Canadian sires.

“Silent Name was bred in Japan by the Wertheimer brothers from an European pedigree that had heavy doses of North American influences,” he says. “He’s out of a mare by Danehill, and his second dam is by Blushing Groom. You’ve got Raja Baba, a son of Bold Ruler, in there, too. So it’s a really international pedigree.

“To build this kind of family requires the ability to think long term, and it’s a long process. Credit to the Wertheimer brothers as they had the vision and sight to send mares to Japan and tap into these different bloodlines. Credit to the Wildenstein family and Maria Niarchos for doing the same as well.”

Contraction

Are we closing in on a situation where the breed might be contracting too much?

“Any answer will be determined on what you are trying to breed,” says Craig. “A sound racehorse with a turn of foot or successful sales horse? Do you prefer to out-cross bloodlines, or are you happy to concentrate on currently successful bloodlines to meet market fashion and sell well?

“For me, primarily trying to breed racehorses, I find it increasingly restrictive simply because so many of the broodmares are by or out of the current stallions. That is an increasing problem, and I see the same in yearlings at sales.

“We can make statistics to say anything, but what they do show is that speed is essential for a racehorse. But class speed. Sadly we are now in a world where cheap speed sells, and class stamina is overlooked or not wanted at the sales.”

The power of the commercial market is certainly a factor.

As Bell notes, most breeders are in the position of having “to play the commercial card.”

“The reduction of the foal crop is also something that’s at play here,” he says. “When you’re going down from 35,000 foals to 19,000, you’re going to get limitations. So we’re playing with the cards that we’re dealt.”

Away from commercial dictations, the shift can also be attributed to the overwhelming influence of Northern Dancer, a great-great-grandson of Phalaris.

Bred by E.P. Taylor, it is part of racing folklore how the late May-foaled Northern Dancer was shunned by buyers on account of his size as a yearling yet went on to win the Kentucky Derby in record time several weeks short of his actual third birthday.

Northern Dancer was sired by a horse, Nearctic, whose female family had been imported by Taylor out of Britain in the early 1950s. At stud, he wasted little time in transcending the gap between North America and Europe, with the deeds of his second-crop son, 1970 Triple Crown winner Nijinsky, prompting a heightened interest in the stallion that was subsequently justified through the likes of Sadler’s Wells, El Gran Senor, The Minstrel, Secreto, Lyphard and Nureyev.

Today, the breed is awash with Northern Dancer, particularly in Europe.

“You look at the role that Northern Dancer played,” says Bell. “He’s by far the most significant. And we’re now seeing Northern Dancer on Northern Dancer work. Delving further in, Danzig on Danzig is more prevalent and can work. Sadler’s Wells on Sadler’s Wells can also work, as we saw with Enable [who was inbred 3x2 to the stallion].”

The idea of major breeders experimenting by doubling up on bloodlines is nothing new.

Ultimus, an unraced but successful sire bred in 1906 by James Keene, was inbred 2x2 to Domino. In Europe, the breeding empire belonging to Marcel Boussac rested primarily upon the influences of his stallions Asterus, Teddy, Pharis and Tourbillon. Indeed, his 1949 Arc heroine Coronation was inbred 2x2 to Tourbillon.

More recently in Australasia, Danehill has become so powerful that in some cases it is hard to get away from his influence. To date, there are no fewer than 15,400 foals inbred to Danehill worldwide—310 of whom are stakes winners. While the list contains various Australian heavyweights such as Verry Elleegant, Farnan, Alizee and Bivouac, it is also interesting to note the number of Australasian farms who market their stallions as being free of Danehill blood when the opportunities arise.

Yet while history tells us that some people will never hold back from multiplying on lines, surely the concentration of today’s sirelines poses some quandaries for breeders.

While Round Table was the North American champion sire of 1972, his place was taken 10 years later by His Majesty, a son of Ribot. By 1992, Northern Dancer was changing the landscape; Danzig was champion in America while in Europe, Sadler’s Wells was in the midst of a championship run that would come to consist of a record 14 sires’ titles. Sadler’s Wells’ own son El Prado broke through with his own American sires’ championship in 2002, and remains a firm influence today via Kitten’s Joy and Medaglia d’Oro.

At the same time, the faster and more precocious Storm Cat, a grandson of Northern Dancer via Storm Bird, was gaining traction on both sides of the Atlantic that would come to be reflected in the successes of Into Mischief, Giant’s Causeway and Scat Daddy—all of whom remain extremely powerful and commercial forces in 2022.

Meanwhile, the Mr. Prospector sire line flourished, whether it be through the likes of Gone West (sire of Elusive Quality, Zafonic, Speightstown and Mr. Greeley), Forty Niner (sire of Distorted Humor and End Sweep), Smart Strike (sire of Curlin) or Fappiano, who has become an increasingly powerful force via Unbridled and Candy Ride.

The Seattle Slew line has consolidated its place as one of America’s best, notably through A.P. Indy and his son Pulpit, who has been so ably represented in recent years by Tapit.

However, all this has come at the expense of other sire lines. Granted, not all of them possessed the vigor to remain relevant. But others were popular and successful options of their time and merely fell foul of commercial desires.

For instance, would Sunday Silence have been so successful had he stood in Kentucky? As it was, Arthur Hancock of Stone Farm attempted to stand his Kentucky Derby winner but support for the horse—one who had been unsold at $17,000 as a yearling and in possession of a light female pedigree—was underwhelming; and he was sold to Japan, where he became an incredible success. While his blood today saturates the breed in Japan, Kentucky options belonging to his sire Halo are limited.

Other causes include a combination of geography, value and circumstances, says Craig.

Ribot at Darby Dan Farm, 1960

“Horses were at one time mainly bred to be raced by their breeders,” she says. “The public sales market was to dispose of those that were not wanted. Mares also often visited stallions that were local and then with time and travel, they went further afield; and a center such as Newmarket began to develop for breeding as much as racing.

“Walter Haefner [Moyglare Stud Farm founder] was one of the first breeders to ship mares by air to Kentucky. He was very wealthy and loved U.S. racing. He sent two mares from Ireland in 1968, primarily to breed to Sea Bird and Ribot. Irish Lass produced Irish Bird, the dam of Assert and Bikala, to Sea Bird. Another mare, White Paper, produced Gp. 1 winner Carwhite to Caro.”

Craig touches upon the wealth of European runners available in America at that time, with Nureyev, Lyphard, Riverman, Irish River, Blushing Groom, The Minstrel, El Gran Senor, Storm Bird, Sir Ivor and Vaguely Noble, among those to leave a lasting impact alongside Sea Bird, Ribot and Caro.

“Many of the top European stallion prospects were abruptly sent to the U.S. in the 1970s due to fear of equine abortion [prompted by the contagious equine metritis (CEM) outbreak in 1977],” she says.

“Comparing stud fees and yearling values in the 1950s and 60s to those at the end of the 1970s and onward shows a vast change, maybe originating in the U.S. as a result of CEM and the flight of leading stallions from Europe, [which] then migrated quickly back to Europe.

“I will always remember attending a Matchmaker seasons and shares auction in the old Radisson in downtown Kentucky in the late 1980s and watching a Northern Dancer season make $1 million. Big business arrived into breeding and as a result into sales, and as we all know, much of this current industry is dictated by fashion. Traditional owner/breeders continued but increasingly found the associated stud fee and broodmare costs limiting.

“Commercial breeders are guided by fashion, and so stallions have to fit the commercial parameters in order to get enough mares; and currently early success and speed are everything. Proven, fast, good looking and recognizable—that doesn't leave many spots for the tough old stallions doing it the hard way. Would Persian Bold have made a stallion now? Would Broad Brush? Both were more than able to get a higher percentage of top performers than the speedy two-year-old performer that gets three times the number of mares.

“And with increased commerciality and 'fashion' came numbers. Fashion and commercial aspects meant that everyone [wanted] to breed their mares to the same sire or sire line, and others were ignored.”

She adds: “Yes, we need the class stamina lines of Roberto, we need Halo, we need Princequillo and Ribot. But they are not flashy or speedy, and sadly not fashionable. Hence the demand is poor, and so those sire lines fade into history.”

Craig laments the contraction of the Grey Sovereign line: “There was a brilliance to those, also temperament, but they worked on all surfaces and in different countries.” Similarly, she is disappointed to witness the contraction of that belonging to Never Bend, a “line of class and brilliance” that supplied Mill Reef and Riverman.

For Headley Bell, use of the Roberto sire line has yielded great rewards.

“Hail To Reason and his son Roberto is such a powerful line,” he says. “I’ve played Roberto and I used Dynaformer a lot with success—our client Lael Stable bred [Kentucky Derby winner] Barbaro by him. I played Halo, more recently through his grandson Hat Trick, the sire of Win Win Win [a Gr. 1-winning homebred for Live Oak Plantation].

“I was also a big Stop The Music player back in the day, although he was different to most Hail To Reasons; he was typey with more speed.”

Of course, the subject of bloodlines isn’t as cut and dry as favoring one sire line over the next. Each stallion represents a blend of influences and as such, opportunities are there to be tapped into.

“Ribot and Roberto remain influential,” says Bell. “In Reality, Relaunch, Fappiano—they are all common threads as well. The Rough N’ Tumble line has been hugely influential—we see him today playing an important role through his son Dr. Fager, the damsire of Fappiano. And that pays tribute to John Nerud and those Tartan Farm families. They bred all those good horses: In Reality, Dr. Fager, Unbridled, Quiet American; and they remain relevant today.”

Independently, Craig was also quick to pay tribute to the impact left by Nerud.

“Tapit is the Bold Ruler - Seattle Slew line, but maybe his real success is due to those tough old Tartan Farm bloodlines,” she says, alluding to the fact that Tapit’s dam, Tap Your Heels, is a daughter of Unbridled (bred on the Fappiano - Dr. Fager cross) and also inbred twice to In Reality.

There is an argument to think that the health of the Thoroughbred is not going to benefit from the current situation. Sure, North America is home to an array of accomplished sires, but at the same time, the variety of several decades ago—an era when some would argue that the breed was sounder and more durable—is lacking.

While Northern Dancer and Mr. Prospector cast a shadow over the top echelons of the 2021 champion sires’ list, there is also a similarity to the next big names, among them runaway champion first-crop sire Gun Runner who represents a fusion of Fappiano, to whom he is inbred, and Storm Cat. Another successful freshman, Practical Joke, represents Into Mischief over Distorted Humor and therefore broadly speaking, Storm Cat over Mr. Prospector.

“It is both a luxury and expensive to be an owner/breeder now,” says Craig. "Most breeding is trial and error. For sure, you can afford to take a few chances—breed to Saxon Warrior or Study Of Man [both sons of Deep Impact based in Europe], keep a few mares in the U.S. or Australia to try to use more of a variety of sire lines, but it is a challenge. There are limited options, and I think we are breeding a lot of slower horses as a result. We are moving inwards not outwards.”

State Incentives 2022

by Annie Lambert

North American Thoroughbred market breeders saw record sales in 2021, while breeding to race looks equally enticing in 2022. Even a pandemic has not stopped the racing industry from rewarding breeders and owners from producing, purchasing and racing quality horses.

Farm Futures

Spendthrift Farm, Lexington, Kentucky, are continuing with their trendsetting programs – Share The Upside and Safe Bet – following the death of Spendthrift founder and owner B. Wayne Hughes last August. Both programs have been directly copied or modified by other farms due to their obvious significance to breeders.

The Spendthrift Farm 2022 Stallion Roster consists of 25 sires, including newly added Basin (Liam’s Map), Known Agenda (Curlin), Yaupon (Uncle Mo) and By My Standards (Goldencents).

Safe Bet minimizes risk for mare owners by ensuring that the stallion they chose from the program will sire at least one graded/group stakes winner by December 31, 2022 from its first two-year-old crop, or the mare owner will owe no breeding fee. If the stallion does produce at least one black-type winner, the listed stallion fee would be due.

Spendthrift stallions in the program for 2022 include Cloud Computing, Free Drop Billy and Mor Spirit, all standing for a $5,000 fee.

“Safe Bet will continue this year with Free Drop Bill, Mor Spirit and Cloud Computing,” verified Spendthrift Stallion Sales Manager Mark Toothaker. “If they do not have a graded stakes winner in North America in 2022, then all of those contracts done under the program will be free. If they have a graded stakes winner, [breeders] are thrilled to death to pay $5,000. If it doesn’t work out, at least it doesn’t cost them anything, as far as a stud fee.”

Share The Upside has proved stunningly successful for breeders, while remaining a simple concept. Breed a mare to a program stallion, have a live foal and pay the stallion fee when due. That foal entitles the mare owner to a lifetime breeding to the stallion, an annual breeding share, with no added costs.

Program stallions for 2022 include: Basin, By My Standards, Known Agenda and Rock Your World (Candy Ride (ARG)), the latter two being already sold out.

“We have two different forms of Share the Upside,” Toothaker said. “Rock Your World and Known Agenda are both on two year programs with fees of $12,500 this and next year. Basin and By My Standards are both on one-year deals with a second year breed back for free. They are both standing at $8,500 one time and then in 2023 you breed a mare for free and you will have filled your commitment to have a lifetime breeding right.”

According to Toothaker, some stallions offer a pay-out-of-sale proceeds type offer this year. It is not a forgiveness of the stud fee, but it is a deferment arrangement.

“There are certain stallions that we will allow a breeder to defer paying the stallion fee, temporarily,” Toothaker said. “They can sell the mare in foal or sell the resulting weanling or yearling. We don’t usually want to carry it past a yearling season.”

Because the quality stallions can be very expensive to acquire, farms must try and turn each season into monetary income if at all possible. Various programs enable stallions to be marketed for the benefit of the stallion business and mare owners.

The Kentucky Thoroughbred Development Fund (KTDF) has increased purses within the state and has shown significant growth. Keeneland Race Course, for example, will award a record $7.7 million for 19 stakes to be run during their April 2022 spring meet.

Spendthrift’s 2022 ‘Share the upside’ program stallions include Rock your world, known agenda, Basin & By my standards (pictured)

The KTDF will contribute $1.5 million to the stakes purses, pending approval from the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission. KTDF funds come from one-percent of money wagered on live Kentucky Thoroughbred and historical racing. In addition, two-percent of all money wagered on Thoroughbred races via inter-track wagering and whole card simulcasting.

Only Kentucky-sired and Kentucky-foaled horses that are registered with the KTDF are eligible for these purse supplements. Each racetrack, pending approval by the KTDF advisory board, decides the purse payment structure. Payment is distributed to the owner of record.

State Lures

The California Breeder’s Association continues to have one of the most respected, and often copied, programs in North America. According to Mary Ellen Locke, Registrar and Incentive Program Manager, there have been no structural changes to their lucrative program from recent years.

California mare owners can breed to out-of-state stallions and still have a Cal-bred, providing the mare foals in the Golden State and is bred back to a California stallion.

“We have no new changes for 2022,” Locke confirmed of the CTBA incentives. “There have not been as many inquiries from other states regarding our program recently. When most were starting out, they’d ask how our program worked. I think a lot of the states that want an incentive program have one.”

Little Red Feather Racing Club is an established racing partnership group, which purchases prospects to race across North America. Founder and managing partner, Billy Koch, made it clear they are not in the breeding business, but definitely keep owner incentives in mind for his runners.

“We race everywhere in the country, so we look at the horses [bred in any state],” Koch explained. “Whatever racing jurisdiction you are running in, the incentives should be noted. When it comes to California, as they say, ‘It pays to own a Cal-bred.’”

Texas has been making big improvements for breeders to take advantage of in recent years, according to Mary Ruyle, Texas Thoroughbred Association Executive Director. Texas state legislatures passed a bill in 2019, which provides for $25 million annually to help the equine industry – seventy percent is set aside for purses. The monies are collected via a tax on equine goods and products.

The TTA is actively promoting the Texas-bred Thoroughbred in 2022.

“What we are doing is going to each of the Texas Class One tracks and inviting new people to learn more about the process of becoming a breeder or a racehorse owner,” Ruyle said. “We’re also having an event in connection with our two-year-old training sale.”

Berdette Felipe, Arizona Thoroughbred Breeders Association, reported there were no major changes to their program, but that business was going well for breeders and owners.

“Turf Paradise has added money into the purses, the purses are bigger,” she said. “And, Turf Paradise does pay a breeder and owner award at the end of the meet.”

Mare owners in Arizona are able to breed to out-of-state stallions, similar to California, and still have an Arizona-bred foal. “As long as the mare foals here and the baby stays in Arizona for six months of its first year,” Felipe explained.

When Virginia passed their Historical Horse Racing legislation in 2019 Debbie Easter, Executive Director of the Virginia Thoroughbred Association (VTA), predicted good things for Colonial Downs. Last year, Easter began to see the numbers climbing in spite of no year around racing in Virginia.

Colonial Downs enjoyed a record setting Thoroughbred season in 2021 with purse monies of $522,000. That number is expected to grow to $600,000 this year. The Virginia Racing Commission also granted the 2022 meet an additional nine days of racing.

The VTA continues to provide incentives to their breeders, encouraging them to set up shop and grow in their state.

Even though the state of Minnesota has challenges for breeders and owners, those directly involved continue to stride forward with help from the Minnesota Thoroughbred Association and the Minnesota Breeders’ Fund [MBF].

The MBF, which is overseen by the Minnesota Racing Commission (MRC), awarded over $600,000 to breeders last year. Monetary awards are paid to Minnesota-bred horses that are registered with the MRC. There are ongoing attempts to promote state-bred horses.

“Members of the commission have agreed recently to support an incentive whereby anyone who buys a share in a Minnesota Thoroughbred Association stallion auction will be rewarded,” Bob Schiewe, Deputy Director of the MBF, explained. “If you bring your mare to use the breeding and bring the mare back to Minnesota to foal, the Breeders’ Fund will pay a $1,000 incentive.

“It’s not a lot in the bigger picture, but it is something. We are hoping that it might result in 15 to 30 mares foaling in Minnesota that otherwise may not have.”

Minnesota not only suffers from severe winter weather. Lower purses at Canterbury Park, the only Thoroughbred track, are stressing the racing structure.

“Canterbury Park, where we have had Thoroughbred and Quarter Horse racing since the 1980s, has a marketing agreement with the nearby Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux community, which owns/operates the Mystic Ways Casino,” Schiewe said. “The casino is very successful and has supplemented purses at Canterbury Park by about $7.5 million annually for 10 years. It basically doubled our purse account.”

But, much to Schiewe’s dismay, the decade long agreement with the casino to provide the added funding is expiring and the Native American community seems prepared not to negotiate a new contract.

“Unfortunately for horse racing in Minnesota,” Schiewe acknowledged, “it seems to be in very serious jeopardy of going away.” “You can do the math; we’ll be losing half of our purse account in this day and age.”

Mr Monomoy

Independent Initiatives

Sean Feld is Managing Director of Climax Stallions, which he runs from Lexington, Kentucky. Sean’s father, Bob Feld of Bobfeld Bloodstock is the company’s Director of Stallion Acquisitions.

Climax Stallions now offer seven sires, most of which reside in varied regions of the United States, with one currently standing in Ireland. The concept of treating each stallion separately allows the company to find proper exposure for each horse.

“When we acquire a stallion we’ll make phone calls to various farms in various locations where we think the horse fits best and where we think he will get the best reception,” Sean explained. “Curlin To Mischief [a half-brother to Into Mischief and Beholder by Curlin] is in California because it was helpful that Into Mischief and Beholder did their running out there. That familiarity definitely helps.”

Son Of Thunder, a full-brother to the late Laoban, stands in New York, St Patrick’s Day, by Pioneerof The Nile, resides in Florida and Mr. Monomoy, by Palace Malice, is in New York. Editorial, a half-brother to Uncle Mo by War Front, and Fortune Ticket, a full-brother to Gun Runner, are both in Maryland. The only stallion standing outside of North America is Bullet Train by Sadler’s Wells.

“We have Bullet Train leased to a national hunt farm in Ireland,” Sean said. “He’s going to be a steeplechase stallion. His first foals in Ireland are three, so they’ll start running soon.”

Climax Stallions are placed with consideration of breeder and owner awards offered as well. Mr. Monomoy, with his dirt pedigree fit well in New York considering the amount of money in the Stallion Stakes races as well as winter races in Aqueduct being run solely on dirt.

State-bred programs like California, Florida, New York and Maryland all have outstanding incentive programs overall, according to Sean. And, Sean appreciates mare owner programs like those offered by Spendthrift.

“We offer a Share the Upside type program for all our freshman sires,” he pointed out. “In the regional market it is a lot harder to compete than the Kentucky market. You have to be creative to get as many good mares as you can. There are leading breeders in every state and you try to get as many mares from leading breeders as possible.”

“Our tagline is, ‘We bring Kentucky to you,’” he added. “We have Kentucky quality pedigrees in the regional market; we try to help the regional-bred horses as much as possible in the pedigree department.”

Ontario, Canada’s province most entwined in Thoroughbred racing, sports a range of incentives to promote Thoroughbred breeding in the province.

There are monetary bonuses allotted through the Mare Purchase Program that applies to in-foal mares with progeny of 2022 when purchased at an Ontario Racing recognized public auction. Through the Mare Recruitment Program, a breeder who brings an in-foal mare to Ontario to foal in 2022 is eligible for incentive funds, with some stipulations.

A breeder of record is eligible for several bonuses through the Thoroughbred Improvement Program, including out-of-province breeders awards. Ontario sired purse bonuses are also paid out. There are many angles to beef up breeder awards in Canada.

It would quite possibly take the entire magazine to explain each and every North American opportunity for mare owners to enhance their bottom lines. The more you dig, the more opportunities are found. And, with competition growing, there are certainly deals to be made. You won’t know until you ask.

Antimicrobials in an age of resistance

By Jennifer Davis and Celia Marr

Growing numbers of bacterial and viral infections are resistant to antimicrobial drugs, but no new classes of antibiotics have come on the market for more than 25 years. Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria cause at least 700,000 human deaths per year according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Equivalent figures for horses are not available, but where once equine vets would have very rarely encountered antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, in recent years this serious problem is a weekly, if not daily, challenge.

The WHO has for several years now, designated a World Antibiotic Awareness Week each November and joining this effort, British Equine Veterinary Association and its Equine Veterinary Journal put together a group of articles exploring this problem in horses.

For more information: https://beva.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/hub/journal/20423306/homepage/sc_antimicrobials_in_an_age_of_resistance

How do bacterial populations develop resistance?

Certain types of bacteria are naturally resistant to specific antimicrobials and susceptible to others. Bacteria can develop resistance to antimicrobials in three ways: bacteria, viruses and other microbes, which can develop resistance through genetic mutations or by one species acquiring resistance from another. Widespread antibiotic use has made more bacteria resistant through evolutionary pressure—the “survival of the fittest” principle means that every time antimicrobials are used, susceptible microbes may be killed; but there is a chance that a resistant strain survives the exposure and continues to live and expand. The more antimicrobials are used, the more pressure there is for resistance to develop.

The veterinary field remains a relatively minor contributor to the development of antimicrobial resistance. However, the risk of antimicrobial-resistant determinants traveling between bacteria, animals and humans through the food chain, direct contact and environmental contamination has made the issue of judicious antimicrobial use in the veterinary field important for safeguarding human health. Putting that aside, it is also critical for equine vets, owners and trainers to recognize we need to take action now to limit the increase of antimicrobials directly relevant to horse health.

How does antimicrobial resistance impact horse health?

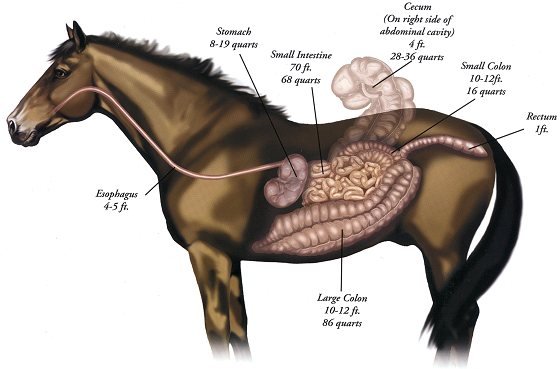

Fig 1. This mare’s problems began with colic; she underwent surgery to correct a colon torsion (twisted gut). When the gut wall was damaged, bacteria easily spread throughout the body. The mare developed an infection in her surgical incision and in her jugular veins, progressing eventually to uncontrollable infection—resistant to all available antimicrobials with infection of the heart and lungs.

The most significant threat to both human and equine populations is multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli, MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecium, and rising MDR strains of Salmonella spp. and Clostridium difficile. In an analysis of 12,695 antibiograms collected from horses in France between 2012-2016, the highest proportion (22.5%) of MDR isolates were S. aureus. Identification of ESBL E.coli strains that are resistant to all available antimicrobial classes has increased markedly in horses. In a sampling of healthy adult horses at 41 premises in France in 2015, 44% of the horses shed MDR E.coli, and 29% of premises shedding ESBL isolates were found in one third of the equestrian premises. Resistant E. coli strains are also being found in post-surgical patients with increasing frequency.

Fig 2. Rhodococcus equi is a major cause of illness in young foals. It leads to pneumonia and lung abscesses, which in this example has spread through the entire lung. Research from Kentucky shows that antimicrobial resistance is increasingly common in this bacterial species.

Of major concern to stud owners, antimicrobial-resistant strains of Rhodococcus equi have been identified in Kentucky in the last decade, and this bacteria can cause devastating pneumonia in foals. Foals that are affected by the resistant strains are unlikely to survive the illness. One of the leading authorities on R.equi pneumonia, Dr. Monica Venner has published several studies showing that foals can recover from small pulmonary abscesses just as quickly without antibiotics, and has pioneered an “identify and monitor” approach rather than “identify and treat.” Venner encourages vets to use ultrasonography to quantify the infected areas within the lung and to use repeat scans, careful clinical monitoring and laboratory tests to monitor recovery. Antimicrobials are still used in foals, which are more severely affected, but this targeted approach helps minimize drug use.

What can we do to reduce the risk of antimicrobial resistance?

The simple answer is stop using antimicrobials in most circumstances except where this is absolutely avoidable. In training yards, antimicrobials are being over-used for coughing horses. Many cases are due to viral infection, for which antibiotics will have little effect. There is also a tendency for trainers to reach for antibiotics rather than focusing on improving air quality and reducing exposure to dust. Many coughing horses will recover without antibiotics, given time. Although it has not yet been evaluated scientifically, adopting the identify and monitor approach, which is very successful in younger foals, might well translate to horses in training in order to reduce overuse of antimicrobials.

Fig 3. Faced with a coughing horse, trainers will often pressure their vet to administer antibiotics, hoping this will clear up the problem quickly. Many respiratory cases will recover without antibiotics, given rest and good ventilation

Vets are also encouraged to choose antibiotics more carefully, using laboratory results to select the drug that will target specific bacteria most effectively. The World Health Organization has identified five classes of antimicrobials as being critically important, and therefore reserved, antimicrobials in human medicine. The critically important antimicrobials which are used in horses are the cephalosporins (e.g., ceftiofur) and quinolones (e.g., enrofloxacin), and the macrolides, which are mainly used in foals for Rhodococcal pneumonia. WHO and other policymakers and opinion leaders have been urging vets and animal owners to reduce their use of critically important antimicrobials for well over a decade now. Critically important antimicrobials should only be used where there is no alternative, where the disease being treated has serious consequences and where there is laboratory evidence to back up the selection. The British Equine Veterinary Association has produced helpful guidelines and a toolkit, PROTECT-ME, to help equine vets achieve this.

How well are we addressing this problem?

Disappointingly, in a recent review of prescribing behavior of three “reserved” antimicrobials at first-opinion equine practices in the USA and Canada between 2006-2012 published in Equine Veterinary Journal, only 5% of prescriptions for the reserved antimicrobials enrofloxacin, ceftiofur and clarithromycin were informed by culture and sensitivity testing. There was also an overall trend of increased prescribing of enrofloxacin across the study period, and despite increasing awareness of the challenge of antimicrobial resistance, a decreasing proportion of enrofloxacin prescriptions were based on culture and sensitivity results.

Judicious use of antimicrobials for surgical patients

Antimicrobials are commonly used in the perioperative period. In both human and veterinary medicine, antimicrobial use for surgical prophylaxis has been a target for reducing or eliminating inappropriate antimicrobial administration. The British Equine Veterinary Association recommends administration of penicillin pre- and post-operatively for 24 hours for clean surgeries; penicillin and gentamicin pre- and post-operatively for five days for contaminated surgeries; and penicillin and gentamicin pre- and post-operatively for 10 days for complicated surgeries. Furthermore, for uncomplicated contaminated wounds (e.g., hoof abscesses), antimicrobial therapy is not recommended. A 2018 survey of perioperative antimicrobial use among equine practitioners in Australia revealed that most equine vets selected an appropriate antimicrobial agent. However, the dose of penicillin chosen was often suboptimal, and therapy was frequently prolonged beyond recommendations in all scenarios except for castration.

Judicious use of antimicrobials through appropriate routes of administration

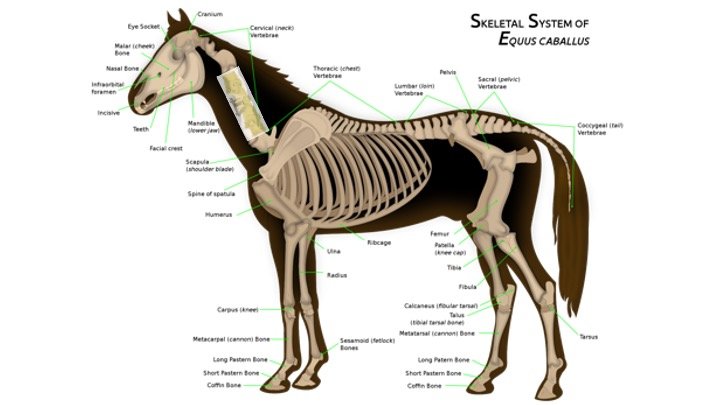

Fig 4. Using antimicrobials as effectively as possible helps to reduce their use overall. For septic arthritis, intravenous regional perfusion of antimicrobials can achieve very high concentrations within a specific limb. This involves placing a temporary tourniquet to reduce blood flow away from the area while the antimicrobial is injected into a nearby blood vessel. The technique is suitable for some but not all antimicrobial drugs.

Due to increasing isolation of MDR organisms, research into local therapy of “reserved” classes of antimicrobials is of interest. Intravenous regional limb perfusion of ceftiofur sodium may be appropriate for septic arthritis but is less clear cut for osteomyelitis.

Oral and rectal administration of antimicrobials are common means to provide cost-effective and convenient treatment options for owners. However, these routes of administration can lead to variable absorption and therefore have the potential for subtherapeutic concentrations. Rectal administration of some antimicrobials has been explored in order to provide antimicrobials to horses with diseases that prevent oral administration, such as small intestinal problems or to provide an alternative for horses that find drugs unpalatable and go off their feed. Metronidazole is one of the few drugs for which pharmacokinetic data following rectal administration have been published, but the optimal dosing regimens via this route have yet to be determined.

Clinical conclusions

Given the increasing prevalence of resistant bacteria affecting the equine population, judicious use of antimicrobials is necessary. Trainers and vets must work together to implement this, otherwise before long, we will find we have no effective drugs left. Firstly, in any given situation, we should question whether antibiotics are really necessary.

Appropriate antibiotic selection, as well as choosing the correct dose, frequency, duration and route of administration should all be considered. Veterinarians should encourage culture and sensitivity testing to allow for guided and narrow spectrum therapies whenever possible. It is also important to keep up-to-date with the latest information on drug treatment schedules and be prepared to modify and adapt as new information becomes available. Appropriate antimicrobial stewardship in veterinary medicine will ensure the availability and legal use of antimicrobials remains an option for our equine patients.

The Hirsch family legacy

by Annie Lambert

California’s Bo Hirsch has always relished horse racing, but winning last year’s Breeders’ Cup Filly & Mare Sprint (Gr. 1) with his homebred, Ce Ce, was “icing on the cake.”

“My goodness, what a thrill,” Hirsch remarked about Ce Ce’s championship. “You talk to people that don’t know anything about horse racing, mention winning a Breeders’ Cup, and they ask what it is. I tell them the best comparison I could give was the Olympics. If you win a Breeders’ Cup race, you’ve pretty much won a gold medal. We won a gold medal last year, and I’m tickled pink.”

Ce Ce, a six-year-old by the late Elusive Quality, accelerated near the top of the Del Mar stretch, overcoming a trio of leaders, including defending champion Gamine, to garner the $1 million purse. Ridden by Victor Espinosa, it was trainer Michael McCarthy’s second Breeders’ Cup victory.

Hirsch’s love of the sport harkens back to his father, businessman Clement L. Hirsch, who left giant footprints across the racing industry before his death in 2000 at 85. The elder Hirsch was instrumental in co-founding the Oak Tree Racing Association at Santa Anita as well as the current Del Mar Turf Club organization. Ce Ce’s Breeders’ Cup success at Del Mar was homage to Clement.

Clement also invested in pedigree lines that continue to produce the likes of Ce Ce. And, Bo’s love of his father and appreciation for the sport to which he introduced him could not be clearer.

“I just love this business; there’s nothing like it, you know?” Bo, 73, asked rhetorically. “It’s a grownup toy store—a wonderful toy store.”

Founding Father

Clement Hirsch’s common sense, drive and dry sense of humor no doubt contributed to his success in business and racing. He attended Menlo College near San Francisco during the 1930s.

While still in college, Clement and some friends bought a washed-up Greyhound dog for very little money. The owner was going to euthanize the canine because it was too broken down to race. The boys brought the dog back to good health, ended up racing it and were excited the process culminated with winning some money. That may have been the future horse owner’s first taste of racing, but it was most certainly his catalyst into the business world.

It didn’t take long to figure out the “people person” with street smarts would choose business over school. Having learned about caring for dogs with the Greyhound, Clement—who served a stint in the Marines during World War II—realized people, mostly, fed their pets table scraps in that era. He began selling a meat-based dog food, door-to-door, out of the trunk of his car. The entrepreneur wound up building that effort into Kal Kan Pet Foods, which he ultimately sold to the Mars Corporation that now markets it under their Pedigree label.

By 1947, Clement decided to invest some of his success into Thoroughbred racing. He hired Robert H. “Red” McDaniel, an established trainer in Northern California. They claimed Blue Reading, a $6,500 outlay, which went on to win 11 stakes, including the 1951 Bing Crosby Handicap, San Diego Handicap and Del Mar Handicap, earning $185,000. From that introduction, Clement was hooked; he owned horses for the rest of his life.

Breeders Cup winner CeCe is a third generation homebred, and Hirsch plans on extending the pedigree line

More Horses, Same Trainer

Clement hired Warren Stute to train his horses in 1950—his second and final trainer. Stute remained his trainer until Clement’s death, 50 years later—a feat we may likely never see again.

“My father could be difficult, and Warren had a mind of his own,” Bo pointed out. “I remember someone asking my father, ‘How did you guys stay together so many years? How could you put up with Warren all those years?’ He said, ‘I just turned down my hearing aide.’”

“It worked,” Bo added with a laugh.

The line of bloodstock that Ce Ce hails from began when Clement attended a sale at Hollywood Park in March 1989. Upon walking in, Mel Stute, Warren’s brother, was bidding on a horse. Mel told his brother’s owner the horse was going over his price range, but that it was worth the money. Clement did make one bid, which dropped the hammer at $50,000.

Hirsch could hardly believe he bought a horse with one wave of his arm, but the result was fortuitous. He had purchased the two-year-old, Magical Mile (J.O. Tobin – Gils Magic, by Magesterial).

The colt won his first out, a maiden special weight, at Hollywood Park just two months later. He broke the track record that day, running the 5-furlongs in :56 2-5, while winning by 7 ½ lengths. He came back in July to win the Hollywood Juvenile Championship Stakes (G2), ultimately earning $131,000 (7-4-0-1) during his career.

“I remember my father being interviewed once when the horse was really doing well,” Bo recalled. “Someone said, ‘You must be getting Derby fever.’ My father said, ‘No, no, no, that’s not realistic; I wouldn’t think in that area, it’s such a long ways off.’ There was a hesitation, then he said to the guy, ‘But, for what it’s worth, we’re trying to get the name Magical Mile changed to Magical Mile and a Quarter.’”

The Howell S. Wynne family owned Magical Mile’s dam, Gils Magic, a mare with no money earned in only one start. Clement tried more than once to buy the mare, but to no avail. He did, however, show up at the sales every time one of her offspring was offered.

“The next great one was Magical Maiden,” Bo said. “He kept trying to buy Gils Magic, but they wouldn’t sell, so he bought what he could from that line. It built up.”

Magical Maiden (by Lord Avie) was a multiple graded stakes winner of $903,245. She is the second dam on Ce Ce’s pedigree. Magical Maiden foaled Ce Ce’s dam, Miss Houdini by Belong To Me in February 2000.

Miss Houdini, trained by Warren Stute, only made a total of four starts at two and three, but managed to win the Del Mar Debutante Stakes (Gr. 1) just about six weeks after a successful maiden special weight debut. Her two wins and a second totaled lifetime earnings of $187,600.

Clement and Warren imported Figonero from Argentina in 1969. The four-year-old stallion was already a winner in his homeland, but he made waves in the United States. Figonero ran third to Ack Ack in both the American Handicap and the San Pasqual Stakes. He won the Hollywood Gold Cup with the late Alvaro Pineda riding. Rumor has it, Stute tore out a wooden deck in his backyard and replaced it with a swimming pool shortly after the Gold Cup.

Pineda was also aboard when Figonero set a world record for 1 1/8 miles while winning the 1969 Del Mar Handicap at Del Mar.

“Figonero was a good one,” Bo remembered. “He ran multiple races in just a few weeks. He won an overnight race, ran third in the American Handicap and came back, ran against [1969 and 1970 co-champion handicap male] Nodouble in the Gold Cup and won the darn thing. They took him back to Chicago in the mud and he didn’t do well, came back here and broke the world record in the Del Mar Handicap.”

“That record lasted about three years until this horse called Secretariat broke it,” he said, chuckling.

Big Ideas

During the late 1940s, Clement got the idea to establish a racetrack in Las Vegas, Nevada.

After acquiring the land and finding investors, Hirsch ran into a multitude of setbacks, which slowed down his project. Eventually the frustrations ended and they had a racetrack. Hirsch brought in some of his own horses to encourage his friends and others to bring more livestock, according to Bo.

“They tried to get it going and it just didn’t work,” the younger Hirsch commented. “[Some local businessmen] offered to buy him out, and he was smart enough to sell. They were only in business for a very short time. I think it was a tough deal there with the heat in the summer and just getting the people to go to the races. They were gamblers, but not racetrackers—a different kind of gambler.”

Hirsch gave Las Vegas a shot and it didn’t work out, but it’s possible his vision was just a little ahead of its time.

By 1968, Clement was securely ensconced in the Thoroughbred industry as a breeder and owner. The businessman had a “never let an idea lay idle'' mindset; so when he noticed unused calendar dates between the summer meet at Del Mar and Santa Anita’s winter meet, the wheels began turning.

Hirsch organized a meeting with Robert Strub, owner of Santa Anita at the time, Lou Rowan, an owner/breeder; and equine insurance broker, veterinarian Jack Robbins and a few others to discuss options for utilizing Santa Anita on those dark dates. The organizers were able to get their dates approved, and the Oak Tree Racing Association at Santa Anita had their opening meet the following fall.

“Once they got approval for the dates, they came back to finalize things with Strub,” Bo said. “Jack Robbins told me the story that they’re in a room and Robert Strub looks up and says, ‘You know, if this thing doesn’t work out, it’s going to cost us, Santa Anita, a few million bucks.’ That was a lot of money in those days. My father said, ‘You’re covered.’ Strub looked at my father and said, ‘You’ve got a deal.’ Then they shook hands, which was the way they did it in those days.”

Pivotal in creating Oak Tree was Clement Hirsch’s concept that the organization be created as a non-profit.

Clement Hirsch (dark jacket), seated alongside his friend and Oak Tree racing association co-founder Dr Jack Robbins and surrounded by other oak tree board members

“None of the board members or executives, which were all horsemen, got salaries,” Bo explained. “For the betterment of the horse racing business, they took all that money and put it back into the business and charitable organizations.”

Shortly after the Oak Tree negotiations, Del Mar (owned by the state of California) came up for an operational bid. Clement put together another group of horsemen figuring the non-profit structure would also work for Del Mar.

“My father put the [Del Mar Thoroughbred Club] group together and they bid for the track and the racing dates,” recalled Bo. “Nobody could compete with a non-profit organization. It was a great idea and, of course, they got it. The same group runs it today; it’s been a very successful organization. I’d like to see more of this happen in horse racing across the country.”

Blended Family

The Hirsch family was an interesting blend of families as Bo was growing up. Clement was married four times, so Bo has full-siblings, half-siblings and step-siblings, which he jokingly calls “a motley group.” He was the only one of those eight kids to take an interest in the racehorses.

“The horse business either gets in your blood or it doesn’t,” Bo opined. “It got into mine; I just loved it the minute I saw it. My father never encouraged me; he thought I was stupid to get in it.”

“He told me I was going to lose my money,” he added with a laugh. “But he loved it, and he couldn’t defend himself for being in the horse business in a practical way. He was successful at it, and I know now why he was in it. I’m in it and I understand: It brings you such joy.”

During the mid-1950s, Clement built his CLH Farm in Chatsworth, outside of Los Angeles. He stood several stallions there over the years, with limited success. When he relocated his family to Newport Beach, he moved the farm to Poway in San Diego County.

Bo said he enjoyed the farm as a kid and did his share of shoveling manure and riding ponies, but he always preferred “to hang out on the front side” at the track.

Similar Guys

Like his father, Bo, who resides in Pacific Palisades, is a businessman. After graduating from the University of Southern California, he worked as a stockbroker until the market dropped in 1972; then he began looking for a different career path.

His father had sold the pet food company but retained a pioneering company, Rocking K Foods, which provided portion-controlled meals for hospitals and the like. There was also a cannery there where the company canned foods for the government to send to the troops in Vietnam.

Out of the blue, Bill Gray, president of the company who ran the operation for the retired Clement, asked Bo if he’d consider leaving the brokerage firm to work for him in sales and marketing. Bo replied, ”When do you want me to start?”

Bo Hirsch

After a short scrimmage with his father over his qualifications regarding a job in the food industry, Bo settled into the job. He ultimately developed the Stagg Chili food lines, which he later sold to Hormel.

“My father always wanted to make sure you knew what you were doing,” Bo explained. “He wanted to make sure you heard both sides of a story, to be sure you were doing what you wanted to do and the right thing to do. He’d always challenge you, take the other side to challenge you and make sure you believed in what you were doing.

“He did it at home with his kids, too. It was a wonderful lesson to learn to get all the facts before you start making decisions—get in there and figure it out. That was just the kind of guy he was and why he was so successful in all the things he ever did.”

Clement’s energy and unique personality lent itself to memorable stories remembered by those who knew him.

“Alan Balch [now executive director of California Thoroughbred Trainers Association] told me the story of Fred Ryan [an executive at Santa Anita at the time] being in a heated phone conversation,” Bo recalled with a chuckle. “Ryan slammed the phone down and, looking at Alan, said, ‘That damn Clement Hirsch—he’d kick a hornet’s nest open just to get a reaction!’”