Gut health - aspects of bad behavior and how to fix it

/By Bill Vandergrift, PhD

When performance horses behave or react in ways that are less than desirable, we as trainers and handlers try to figure out what they are telling us. Is there a physical problem causing discomfort, or is it anxiety based on a previous negative experience? Or, is the bad behavior resulting from a poor training foundation leading the horse to take unfamiliar or uncomfortable situations into their own hands, which usually triggers the fright and flight reflex instead of relying on the handler for direction and stability?

Often when the most common conditions that cause physical discomfort are ruled out, it may be tempting to assume that the bad behavior is just in the horse’s head or that the horse is just an ill-tempered individual. In my experience, most unexplainable behavior expressed by performance horses is rooted in the horse’s “other brain,” otherwise known as the digestive system. In this article I will explain what causes poor digestive health, the link between digestive health and brain function, and what steps can be taken to prevent and/or reverse poor digestive health.

Digestive health

While most trainers are familiar with gastric ulcers, their symptoms and common protocols utilized to heal and prevent them, there still remains a degree of confusion regarding other forms of digestive dysfunction that can have a significant effect on the horse’s performance and behavior. In many cases recurrent gastric ulcers are simply a symptom of more complex issues related to digestive health. Trainers, veterinarians and nutritionists need to understand that no part of the horse’s digestive tract is a stand-alone component. From the mouth to the rectum, all parts of the digestive system are in constant communication with each other to coordinate motility, immune function, secretion of digestive juices and the production of hormones and chemical messengers. If this intricate system of communication is interrupted, the overall function of the digestive system becomes uncoupled, leading to dysfunction in one or more areas of the digestive tract.

For example, a primary cause of recurrent gastric ulcers that return quickly after successful treatment with a standard medication protocol is often inflammation of the small and/or large intestine. Until the intestinal inflammation is successfully controlled, the gastric ulcers will remain persistent due to the uncoupling of communication between the stomach and lower part of the digestive tract.

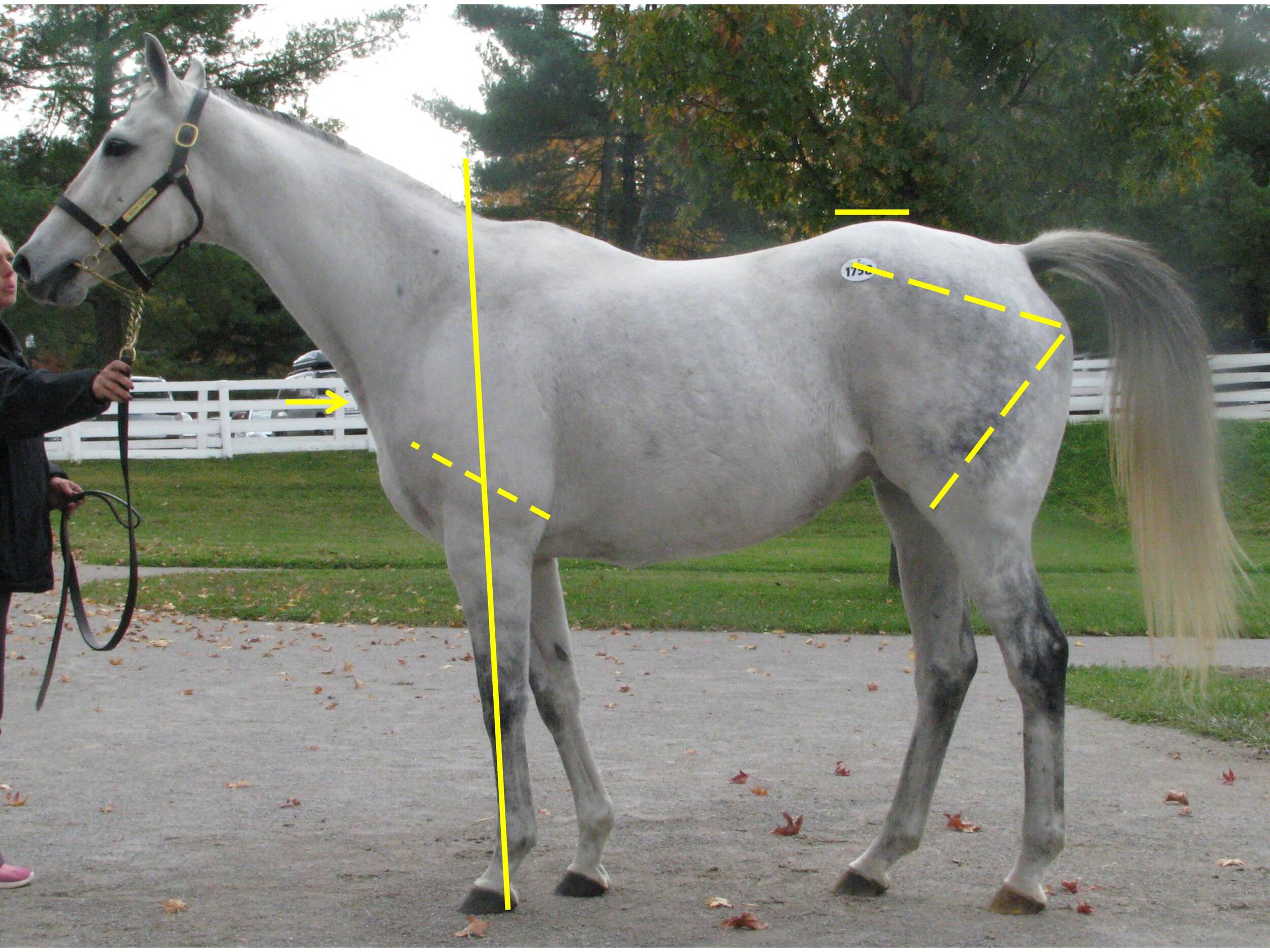

How do we define digestive health? Obviously, digestive health is a complex topic with many moving parts (figuratively and literally). The main parts of a healthy digestive system include, but are not limited to 1) the microbiome, 2) hormone and messenger production and activity, 3) health of epithelial tissues throughout the digestive system, 4) normal immune function of intestinal tissue and 5) proper function of the mucosa (smooth muscle of the digestive tract) to facilitate normal motility throughout the entire length of the digestive tract.

Microbiome is key

A healthy and diverse microbiome is at the center of digestive health. We now recognize that reduced diversity of the microbiome can lead to digestive dysfunction such as colic and colitis, development of metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, reduced performance and increased susceptibility to disease. Research efforts leading to greater understanding of the microbiome have recently been aided by the development of more sophisticated techniques used to identify and measure the composition of the microbiome in horses, laboratory animals, pets, livestock and people. While these research efforts have illustrated how little we really understand the microbiome, there have been significant discoveries stemming from these efforts already. For example, a specific bacteria (probiotic) is now being used clinically in people to reverse depression resulting from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 reduces depression in IBS patients by directly affecting the activity of the vagus nerve which facilitates communication between the brain and the digestive tract. It should be noted that Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 has been demonstrated to be more effective at reducing depression in IBS patients than antidepressant drugs commonly used in these same cases. While we do not commonly recognize clinical depression as a physiological condition in horses, the same mechanisms that affect the function of the vagus nerve and brain chemistry in IBS patients can affect a horse’s behavior and reactivity due to intestinal dysfunction, resulting in a horse that bites, kicks, pins its ears or otherwise demonstrates hyper-reactivity for no apparent reason, especially if this behavior is a recent development.

One case in particular I dealt with years ago that had underlying suggestions of depression in a horse, and underscores the importance of a diverse and healthy microbiome for performance horses, was a horse that had been recently started in training and was working with compliance on the track. The problem was this horse seemed to be unable to find the “speed gear.” The trainer had consulted with various veterinarians, physical therapists, chiropractors and others in an attempt to pinpoint the cause for this horse’s apparent inability to move out; and it was everyone’s opinion that this particular horse had the ability but he simply wasn’t displaying the desire. In other words, he was “just dull.” After reviewing this horse’s case and diet, I had to concur with everyone else that there was no obvious explanation for the lack of vigor this horse displayed on the track even though his body condition, muscle development and hair coat were all excellent. Despite any outward signs of a microbiome problem other than the horse’s “dullness,” I recommended a protocol that included high doses of probiotics daily, and within 10 days we had a different horse. The horse was no longer dull under saddle and when asked to move out and find the next gear, he would readily comply; by making an adjustment to the microbiome, this horse’s career was saved.

There is always a change to the microbiome whenever there is a dysfunction of the digestive system, and there is always digestive dysfunction whenever there is a significant change to the microbiome. Which one occurs first or which one facilitates a change in the other may be dependent upon the nature of the dysfunction, but these two events will almost always occur together. Therefore, efforts to maintain a viable and diverse microbiome will reduce the chances of digestive dysfunction and increase the speed of recovery when digestive dysfunction occurs.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

SUMMER SALES 2019, ISSUE 53 (PRINT)

$6.95

SUMMER SALES 2019, ISSUE 53 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

PRINT & ONLINE SUBSCRIPTION

From $24.95