The importance of stable ventilation

/By Alan Creighton

Over the past 20 years the Irish Equine Centre has become world leaders in the design and control of the racehorse stable environment. At present we monitor the stable environment of approximately 180 racing yards across Europe.

The basis of our work is to improve biosecurity and the general environment in relation to stable and exercise areas within racing establishments. This is achieved by improving ventilation, yard layout, exercise areas and disinfection routines, in addition to testing of feed, fodder and bedding for quality and reviewing how and where they are stored.

Racehorses can spend up to 23 hours per day standing in their stable. The equine respiratory system is built for transferring large volumes of air in and out of the lungs during exercise. Racehorses are elite athletes, and best performance can only be achieved with optimal health. Given the demanding life of the equine athlete, a high number of racehorses are at risk of several different respiratory concerns. The importance of respiratory health greatly increases in line with the racehorse’s stamina. Therefore, as the distance a racehorse is asked to race increases so does the importance of ventilation and fresh clean air.

Pathogenic fungi and bacteria, when present in large numbers, can greatly affect the respiratory system of a horse and therefore performance. Airborne dust and pathogens, which can be present in any harvested food, bedding, damp storage areas and stables, are one of the main causes of RAO (Recurrent Airway Obstruction), EIPH (Exercise Induced Pulmonary Haemorrhage, also known as bleeding), IAD (irritable airway disease) and immune suppression. All of which can greatly affect the performance of the racehorse. Yards, which are contaminated with a pathogen of this kind, will suffer from the direct respiratory effect but will also suffer from recurring bouts of secondary bacterial and viral infections due to the immune suppression. Until the pathogen is found and removed, achieving consistency of performance is very difficult. Stable ventilation plays a huge part in the removal of these airborne pathogens.

What is ventilation?

The objective of ventilation is to provide a constant supply of fresh air to the horse. Ventilation is achieved by simply providing sufficient openings in the stable/building so that fresh air can enter and stale air will exit.

Ventilation involves two simple processes:

Air exchange where stale air is replaced with fresh air.

Air distribution where fresh air is available throughout the stable.

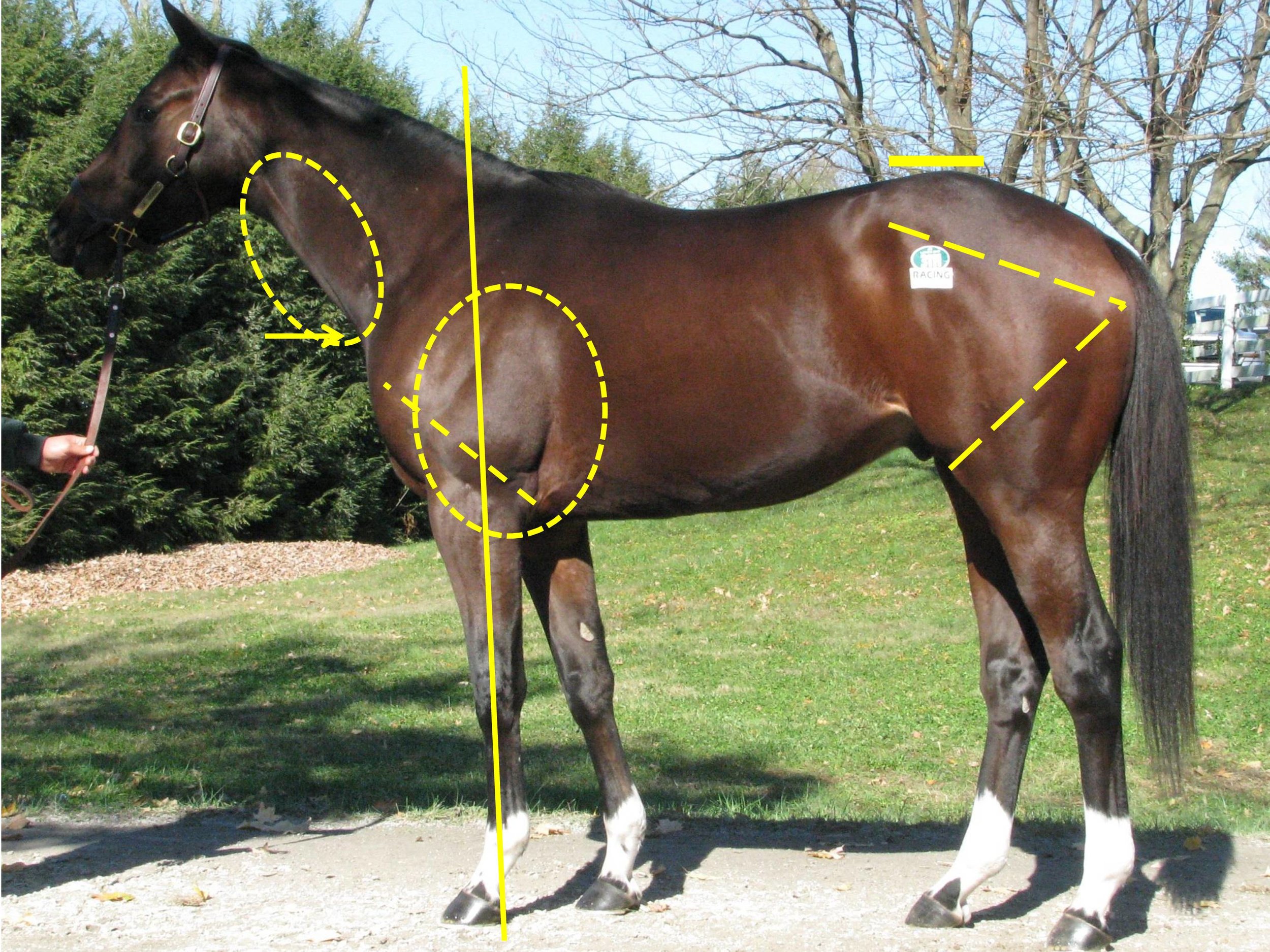

Good stable ventilation provides both of these processes. One without the other does not provide adequate ventilation. For example, it is not good enough to let fresh air into the stable through an open door at one end of the building if that fresh air is not distributed throughout the stable and not allowed to exit again. With stable ventilation we want cold air to enter the stable, be tempered by the hot air present, and then replace that hot air by thermal buoyancy. As the hot air leaves the stable, we want it to take moisture, dust, heat, pathogens and ammonia out as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 2

It is important not to confuse ventilation with draft. We do not want cold air blowing directly at the horse who now has nowhere to shelter. Proper ventilation, is a combination of permanent and controllable ventilation. Permanent ventilation apart from the stable door should always be above the horse’s head. It is really important to have a ridge vent or cowl vent at the very highest point of the roof. Permanent ventilation should be a combination of air inlets above the horse’s head, which allows for intake of air no matter which direction the wind is coming from, coupled with an outlet in the highest point of the roof (shown in Figure 2). The ridge vent or cowl vent is an opening that allows warm and moist air, which accumulates near the roof peak to escape. The ridge opening is also a very effective mechanism for wind-driven air exchange since wind moves faster higher off the ground. The controllable ventilation such as the door, windows and louvers are at the horse height. With controllable ventilation you can open it up during hot spells or close it down during cold weather. The controllable ventilation should be practical and easy to operate as racing yards are very busy places with limited time.

Where did the design go wrong?

The yards we work in are a mixture of historic older yards, yards built in the mid to late 20th century and yards built in the early 21st century. The level of ventilation present was extremely varied in a lot of these yards prior to working with the Irish Equine Centre. Interestingly the majority of the yards built before World War I displayed extremely efficient ventilation systems. Some of the oldest yards in the Curragh and Newmarket are still, to this day, considered well ventilated.

In parts of mainland Europe including France the picture is very different. In general, the older yards in France are very poorly ventilated. The emphasis in the design of yards in parts of France appears to be more focused on keeping animals warm in the winter and cool during the summer. This is understandable as they do get colder winters and warmer summers in the Paris area, for example, when compared to the more temperate climate in Ireland and the UK. When these yards were built they didn’t have the quality of rugs available that we do now. Most of the yards in France are built in courtyard style with lofts above for storage and accommodation. When courtyard stables are poorly ventilated with no back or side wall air vents, you will always have the situation that the only boxes that get air exchange are the ones facing into the prevailing wind at that time. In this scenario, up to 60% of the yard may have no air exchange at all.

In the mid to late 20th century efficient ventilation design appears to have been overlooked completely. There appears to be no definitive reason for this phenomenon, with planning restrictions, site restrictions in towns like Newmarket and Chantilly, cheaper builds, or builders building to residential specifications all contributing to inadequate ventilation.

Barn and stable designers did not, and in a lot of cases still don’t, realize how much air exchange is needed for race horses. Many horse owners and architects of barns tend to follow residential housing patterns, placing more importance on aesthetics instead of what’s practical and healthy for the horse.

Many horses are being kept in suburban settings because their owners are unfamiliar with the benefits of ventilation on performance. Many of these horses spend long periods of time in their stalls, rather than in an open fresh-air environment that is conducive to maximum horse health. We measure stable ventilation in air changes per hour (ACH). This is calculated using the following simple equation:

Air changes per hour AC/H

N = 60 Q

Vol

N = ACH (Air change/hour)

Where: Q = Velocity flow rate (wind x opening areas in cfm)

Vol = Length x Width x Average roof height.

Minimum air change per hour in a well-ventilated box is 6AC/H. We often measure the ACH in poorly ventilated stables and barns with results as low as 1AC/H; an example of such a stable environment is shown in Figure 3. When this measurement is as low as 1AC/H we know that the ventilation is not adequate. There will be dust and grime build up, in addition to moisture build up resulting in increased growth of mould and bacteria, and there will be ammonia build up. The horse, who can be stabled for up to 23 hours of the day, now has no choice but to breathe in poor quality air. Some horses such as sprinters may tolerate this, but in general it will lead to multiple respiratory issues…

![How technology can quantify the impact saddles have on performance[OPENING PIC – half tree.jpg][STANDFIRST]Thanks to advances in technology, it is getting easier for scientists to study horses in a training environment. This, combined with recent sa…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/517636f8e4b0cb4f8c8697ba/1576857005035-HPX4XCF2QZNWYEOZGFCA/PP690W.jpg)